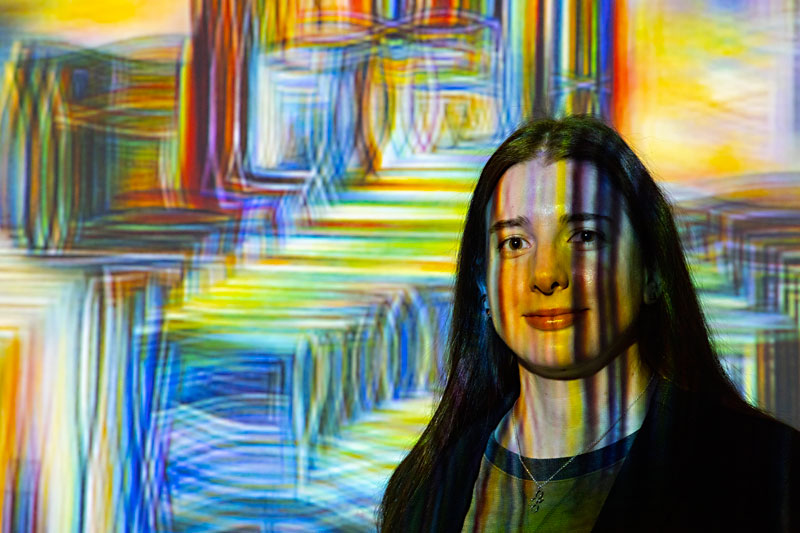

Sorcery and Special K: The Neuroplastic Visions of Zoë Shulman

How ketamine therapy helped the Austin artist transmute her psychedelic insights into gallery gold

By Wayne Alan Brenner, Fri., Feb. 11, 2022

John Dee, the demon-haunted alchemist and court astronomer to England's Queen Elizabeth I back in the 1500s, never got to experience the power of ketamine.

We tell you this for two reasons. 1) Because the first time we reviewed the work of Austin artist Zoë Shulman – in her 2018 solo show "The Allegory of Good and Bad Government" at Camiba Gallery – we described the young artist's creations as "something a more skilled and less gonzo John Dee might've come up with between bouts of angelic possession." And, 2) Because this latest show of Shulman's – "Neuroplastic," also at Camiba and running through Feb. 26 – is all about experiencing the power of ketamine.

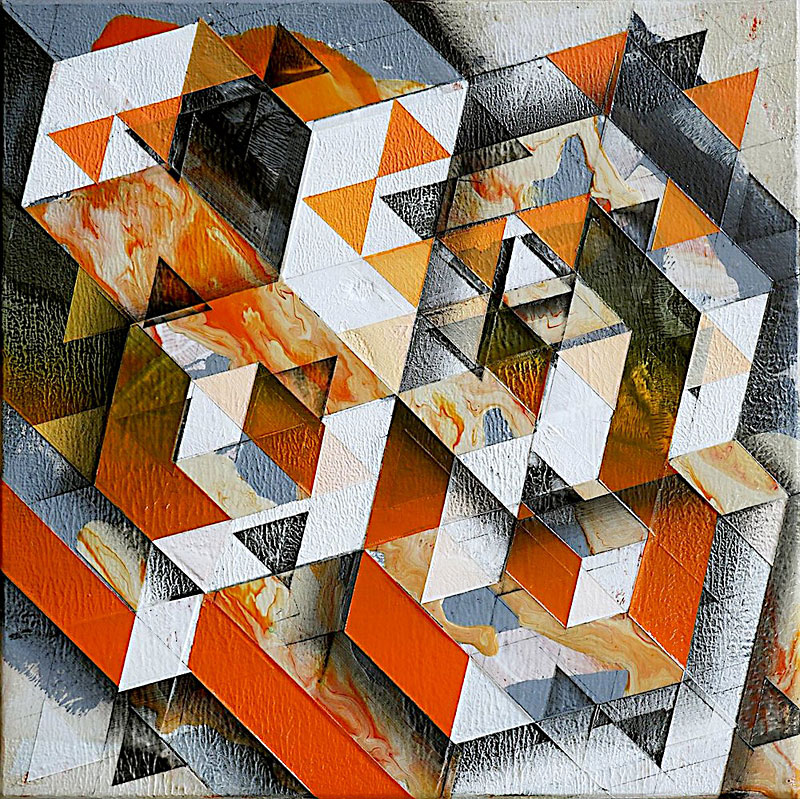

The 32-year-old Austinite started her career with a focus on realism but has worked in geometric abstraction for years. "For this show, specifically," she said, "I had to figure out how I was going to describe these four-dimensional, ketamine-induced polygons. Which, by the way, I call them ketagons." Her easy smile, tinted with a trace of neologism-pride, suggests a distinct lack of depression. "And I was like, 'OK, what do most artists do when they draw something representationally?' Well, they use light and shadow, they use space, they use linear perspective and sight-sizing – all these basic drawing techniques, to get something complex and living onto a 2D surface."

(Note: Ketamine, first synthesized in 1962, is a medical substance that's used in clinical settings to counter treatment-resistant depression. Among recreational users seeking to have their minds chemically blown, it's also known as Special K.)

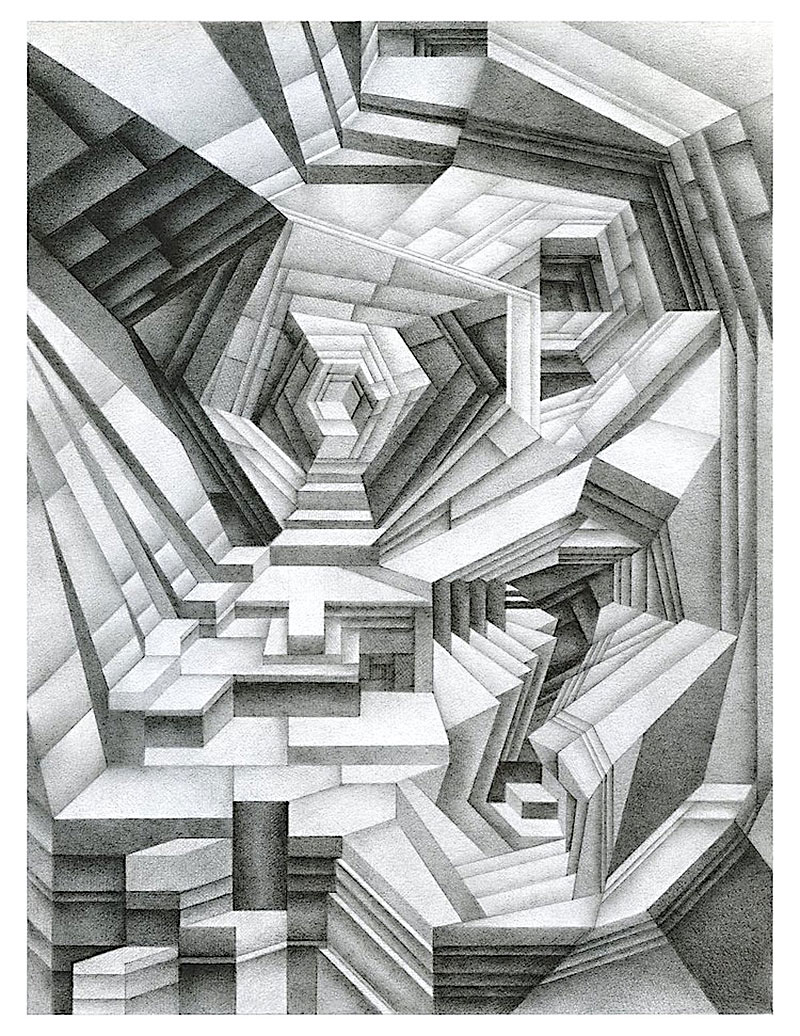

"So I started with graphite pencils," said Shulman, who earned a bachelor of fine art in painting and drawing from the Minneapolis College of Art & Design in 2013, "because I could work very efficiently with light and shadow in my sketchbook. Then, once I'd figured out how to shade the forms, I moved into black-and-white painting. And then I had to figure out, how am I gonna get these drawings to feel painterly?"

Such was the creative challenge in preparing for her current show; but what led Shulman to that point was a more dire problem.

"About three years ago," she said, "I was diagnosed with depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. I went to a psychiatrist and was put on Prozac for the depression and Xanax for the anxiety. And that leveled me out – it got me stabilized, essentially. And I actually had no idea what ketamine was, but I'd inquired about it. And I was told that it's a dissociative drug that can produce a psychedelic experience, but it allows your brain to develop more neuroplasticity by creating temporary bridges – that didn't exist there before – between neurons. You go through a process of neurogenesis. When your brain is really stuck in negative thought patterns, composed by PTSD and depression, the ketamine is a way to switch off those tracks and get onto new circuits – it literally makes your brain more flexible."

So it was the artist and her more flexible brain tackling the production of what's now complicating the Camiba Gallery walls, sussing out practical gambits of depiction. "I started thinking about order and chaos coming together to create complexity," said Shulman. "I started doing glazing and paint pours and a lot of taping-and-cutting and getting hard edges, and doing drop shadows to add to the drama and the overall feel of the subject I was trying to capture. In some cases, I finished with metal prints. I'd do a drawing and then I'd scan it, dragging it across the scanner to make it all warbled and crazy, and then I'd combine those images, cut and collage them and scan those in. And I'd wind up with these negative images, these delicate line drawings, and send them off to get printed on metal."

Earlier, the ketamine treatments had provided an even more urgently needed flexibility. "During psychotherapy, it'd been really hard to address trauma – because the traumatic memory's fragmented and compartmentalized and difficult to verbalize without going into, like, fight-or-flight. But when I did the ketamine, I was able to dissociate and have what I'd describe as loss of ego. I felt completely liberated from the negativity that I had been living in through my body. And it was incredible – I hallucinated these crystal caverns, and they were so mesmerizing, and it was the nicest, friendliest thing that I've experienced, and it – it made me regain my faith."

She paused for a sip of coffee, the action shifting a figurine that's attached to her jacket: It's a second-generation Pokémon, an Unown, which happens to resemble the mystic glyph from John Dee's book Monas Hieroglyphica.

"So that was the mystical part," said Shulman. "But I didn't have the words to describe it until I started drawing the hallucinations I saw. So, in a way, it was kind of representational – because I was trying to render what I'd seen as precisely as I could. And, as I drew, I'd have memories of the psychedelic experience come back, and I'd have words. So I'd draw the picture, and have these flashes of thoughts and feelings, and I'd write down a poem or an essay. And then I'd bring it in to my cognitive behavioral therapist, and we could reframe my thoughts and feelings: Whatever we needed to deal with in the talk therapy could be addressed. That's where I really started to get into the deep side of myself, psychologically – and it entered through the geometric abstractions that I'd already had an interest in."

Aware of popular culture's frequent conflation of heightened creativity and forms of madness, we have to wonder if Shulman – enabled to better plumb her depths via controlled, therapeutic tripping – finds that a valid idea. She responded without hesitation.

"No," said the artist. "That's just kind of a trope, isn't it? It's a trope. There is some truth in it, but – I don't think it's madness or mental illness, specifically, but that it's more like adversity is what pushes humans to be honest and makes for good work. There are multiple right ways to find meaning and to construct it, and the people who are wired to want to do that visually, there's just a word for it: artist. And artists are fundamentally meaning-makers who work with symbols – visual symbols for the most part, but many artists work conceptually, or with theories and not tangible art objects – but there are many ways to consider it. In music, dance, writing, in a lot of things. Even in my father, who's an attorney, I see an art in his practice of constructing an argument for a case: It's a performance – he has to construct a narrative about truth, to show a side – and it's deep and powerful work. There are a lot of people who wear suits and ties who, I believe, are doing art."

And what of the people who provide an audience for such activity? What meaning might they glean from Shulman's latest collection of painstakingly wrought creations?

"What I want people to know about this show is that we need to end the stigma for mental illness. We need to end the war on drugs. We need to make psychedelics more accessible and more affordable – and end the stigma for psychedelic treatment. It's hard for people to wrap their heads around, but the more we engage in conversations about it, the less it's stigmatized and the more accepted it can be. And that's important, because this therapy has an incredible potential to save lives and to address trauma – which society sucks at addressing. If we can use it to get to know ourselves better and to catalyze a healing journey, I think society will be able to avoid a lot of tragedy. I want people to be able to say, 'I have mental illness, I have mental challenges,' and screw the stigma. Seek help if you need it. You know? There's nothing wrong in doing that – it takes strength and courage to seek mental health treatment."

And ancient John Dee – Dee, who sought to translate the Enochian language of angels toward humanity's betterment – would his fraught life have been improved with a course of ketamine-fueled introspection? Zoë Shulman, who has transmuted her psychedelic experiences into complex works of art, might well provide a clue to that mystery.

“Zoë Shulman: Neuroplastic” at Camiba Gallery, 6646 Hwy. 290 E. Ste. A-102, through Feb. 26. Thu.-Sat., 11am-5pm, or by appointment. camibagallery.com.