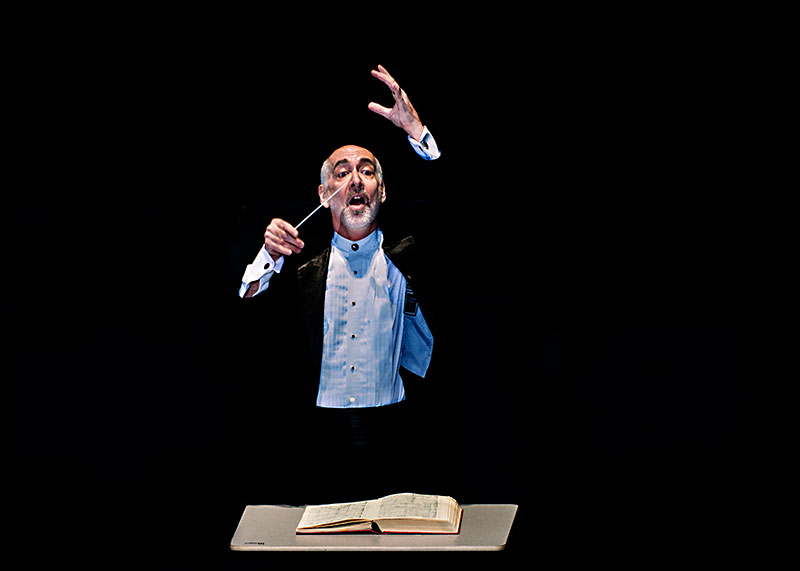

Austin Opera's Of Mice and Men

Artistic Director Richard Buckley on returning to the Carlisle Floyd opera that launched his conducting career

By Robert Faires, Fri., Jan. 22, 2016

Richard Buckley knows a thing or two about the opera Of Mice and Men, and not just because he's conducting the Austin Opera production that runs Jan. 23-31 at the Long Center. Between 1976 and 1982, the maestro conducted Carlisle Floyd's adaptation of the popular John Steinbeck novel 48 times across the U.S., including a version with Houston Grand Opera that traveled to the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., and one at the inaugural – and, sadly, only – New World Festival of the Arts in Miami. Then, Buckley was still in his 20s and just breaking into the world of professional conducting, while Of Mice and Men was even younger and slowly being introduced to audiences in an art form not known for its quickness to embrace new work. Now, Buckley is a highly respected conductor with credits spanning all of North America and Europe, and in his 12th season as Austin Opera's artistic director, and he has programmed Of Mice and Men, which, in the 45 years since its premiere in Seattle, has found a fixed place among operas produced regularly. You might imagine that after dozens of experiences with the work that Floyd's opera would hold no surprises for him, but the passage of time has given Buckley some new perspectives on this particular work, as he shared with the Chronicle in an interview by phone.

Austin Chronicle: What do you recall about listening to the score or working on it with the Seattle Symphony for the first time?

Richard Buckley: I was 23 – I had just turned 23 – and was assigned [the job] by the music director of the opera. I had originally gone to Seattle in '74 to work with the opera, and even though I had switched and was working at the symphony, he was a big supporter of mine, and he had another gig. They used to do six performances with two casts, four with one cast and two with another. And I literally walked into the pit and conducted four performances without any rehearsal with the orchestra.

The big thing was, [the players] had known me as a music assistant, an orchestra manager who was around and taking care of them, doing a lot of administration. They knew I wanted to be a conductor, but they really didn't know of me as a conductor until I walked into the pit and did this. And it was a big change in my relationship with them, you know. They realized I might have something else to offer than taking care of where they sat and whether their stand lights were correct and that type of stuff.

I should also expand on ... I was given the opportunity to do it and said, "Of course" – "Yes! Yes!" – then I looked at the piece, and then I looked at the score, and then I listened to it, and then I went, "Oh my goodness" ... with other expletives. I had to really dig into the challenges of what I was putting myself up to, both from a conducting point of view and also understanding the harmonic language, because although now it doesn't sound that way and I'm so past the point of ever hearing it, I guess, then there were parts that were – some people call it very cinematic, with very atmospheric colors. It's a very typical opera in terms of there's ensembles, there's arias, there's duets, there's trios, but it is in a very American vernacular. Floyd's biggest opera before this was Susannah, and that is very, very nationalistic, folksy, in its musical vocabulary. We're talking about a certain type of Americana rhythmic drive – both a rhythmic complexity and harmonic complexity. So it was probably good that I didn't [know what I was getting into], because I had accepted the challenge and at that time in my life I needed any opportunity I could get. So it was like, "Well, you're doing this, so you better figure it out."

AC: Did you know Floyd's work before that? Had you seen Susannah?

RB: I had not. It was later, after Of Mice and Men, that I saw Susannah. I had done [Douglas Moore's] The Ballad of Baby Doe. In my early childhood, I'd been around both The Ballad of Baby Doe and [Robert Ward's] The Crucible because my father [conductor Emerson Buckley] premiered them in the Fifties. In the Sixties, I was not around much contemporary opera. The only opera I saw was fairly traditional – Verdi, Puccini. Most of my more contemporary music was symphonic repertoire, not operatic repertoire. But I remember coming to this opera and thinking that it was like doing The Rite of Spring. And what I've realized, for sure, is that in the early Seventies, The Rite of Spring for most symphony orchestras was still considered a piece of challenge. Now it's just a standard rep piece that they do on no rehearsal. It's pretty amazing how things progress with regard to that.

And I think audiences now come to this piece and feel it in a totally different way, in a much more user-friendly way just because of what it is, how it has grown, what we are used to. People who have not heard the piece and are hearing it now say, "It's very, very colorful orchestration, and it's very emotional, and it depicts the characters." It's interesting: It's had a strong and steady position in the repertoire, but ... musical theatre pieces like Sondheim, like Sweeney Todd and Les Miz seem to continue to play with great strength. Others kind of go in and out and in and out, not of favor necessarily, but of consciousness.

AC: What made you want to come back to it at this point?

RB: Austin [Opera] had never done it. As artistic director, I feel it's important that my organization visits some American rep occasionally. I get it that in the past the company maybe had done more than what the palate at that time was [ready] for. We made a conscious decision to pull back a bit and do more standard rep. I'm hoping that I've created a following and a trust in the subscribers that they will come to this repertoire in a more open way, with a more open heart, and at least come hear it. I think of so many pieces that are out there, this is really tried and true. It works.

AC: Do you feel the opera successfully captures what it is that makes the story endure, makes us keep wanting to return to Steinbeck's story?

RB: I feel so. I feel that what the opera does, as operas must, is that it synthesizes. It finds the key, most important, salient themes, emotions, and presents them to the listener.

AC: So how has it felt to revisit this opera that you've conducted so many times?

RB: Two major differences that I've been surprised about. One is how different the emotions of a 62-year-old are than a 23-year-old when dealing with the story, both emotionally and also with that much more development in not only my own personal life, my own professional life, my own artistic life, but also the development of stories and ideas, the development of music, the musical vocabulary – how it was perceived and felt when it was written and how it was stacked up against other music at that time. Coming to it now with all that has happened, it's very, very different. So that's one big category.

The other big category is that an orchestra of 2016 comes to a piece that was written in 1970 with a whole different development of rhythmic and harmonic understanding. In other words, you know, to have something in multiple meters and every bar changing, you know, there's a groove to it, and they're playing it off the page with much more facility than did orchestras in the Seventies. That actually surprised me – happily. It's still: They gotta learn it, they gotta know it, they gotta see where the kinks are, they gotta see where the awkwardness of certain bars are, but they're coming to the score already at a much higher level than orchestras could then.

AC: Elaborate a little on the emotional changes you feel between then and now.

RB: Sure. There are two major dramatic themes in the piece that are revisited by different characters. One is the dream of a certain life in the future. The dream of Lennie and George is to have a house and a farm that they own, that they can control, where nobody else can tell them what to do. Candy, the old ranch hand, whose old dog is killed at the end of the first act – the ranch hands say his dog is mangy, it's time for him to go, put him out of his misery, which, of course, is the fear of Candy, because he has a mangled hand and he's old and he's kind of useless – he pairs up with Lennie and George with the same dream of having a little farm. Curley's wife has a dream of being a movie star and always being attractive and admired and fondled by men – well, fondled emotionally, not physically.

The other is the lonesome road of life and that darker side, and there's the character Slim who speaks to that in his aria in the beginning to the second act: "Ranch hands die, and they die alone."

So, dream and loneliness. You're looking at a 23-year-old who has this opportunity, and he's just embracing the beginning of his dreams – in life, in career, in music – and already he's experiencing the fact that to be dedicated to achieving one's goals in my world you push off many things in life. And it was lonely. And that continued on. Until I moved here [in 2004], I was on the road nine months out of the year, by myself. Now, I tried to have a family, had a daughter, blah blah blah, but I was still dealing with all of this alone.

Now, at 62, when I have achieved many dreams, been very fortunate – worked very hard but been very fortunate, there's always luck involved – I've made the decision to have more community in my life. So, although I work hard, I'm not as alone. Then you look at, okay, at 62, actuaries say you'll be lucky if you're alive in 20 more years, so what are the dreams I will look back on and feel I've accomplished, and what are the dreams I can still look forward to [achieving]? I don't mean to be morbid, it's just kind of the emotional fabric that you deal with – not in a verbalized way, but it's what you bring to the fabric when you're having the music run through you and you're reinterpreting it and you're working with other artists doing that.

What's nice about the experience I've had coming back to the music is, I have very little, if any, fear of it because of its technical rhythmic things. So I'm hoping that I have a freer line through the rhythmic realities. When I was less experienced, it would have been much more of a technical rhythmic matter. Now, it's just the way the music flows on a linear basis. In terms of the drama and the big musical moments, they haven't changed off the page, so maybe I know how to shape them more or maybe I'm remembering that that was a hard juncture, and maybe if you shape it a little bit different you can make it more flowing and less jerky, less jagged. And I hope that, because I've dealt with more orchestral colors and orchestral pieces now, that I'm bringing more varieties of sounds and colors from the orchestration, know to get them, know how to say certain things that will communicate an orchestral technique which will provide a different aural experience, an aural color from the instruments themselves.

AC: Are any of the singers people who have done this opera before?

RB: Three of our cast have done it before – interestingly, together – but not for a long time. Five of the cast are doing it for the first time. [The singer playing] Curley's wife, Julia Taylor, is someone who is taking the place of the singer who was originally on board, and she's actually a graduate student – a doctoral student – at the University of Texas. We've used her in several small things, and I hired her as an understudy, and when the person canceled, I said, "Okay, you're on." So we're giving a major professional debut to her, which feels really good. And she's doing a great job.

Much like another young artist did when handed an identical opportunity with this very opera some 40 years ago. Sometimes, what goes around comes around.

Austin Opera presents Of Mice and Men Sat., Jan. 23, 7:30pm; Thu., Jan. 28, 7:30pm; and Sun., Jan. 31, 3pm, in Dell Hall at the Long Center, 701 W. Riverside. For more information, call 512/474-5664 or visit www.austinopera.org.