That Wild Man

Gary Cartwright: The mad, mad, mad life of a Texas wordsmith

By Joe O'Connell, Fri., June 26, 2015

How to write about the memoir of an iconic Texas scribe whose life has been way more interesting/wild/chaotic than yours? Use his words.

"On the road home to Brownwood in her green '74 Cadillac with the custom upholstery and the CB radio, clutching a pawn ticket, for her $3,000 mink, Candy Barr thought about biscuits. Biscuits made her think of fried chicken, which in turn suggested potato salad and corn. For as long as she could remember, in times of crisis and stress, Candy Barr always thought of groceries. It was a miracle she didn't look like a platinum pumpkin, but she didn't: even at 41, she still looked like a movie star."

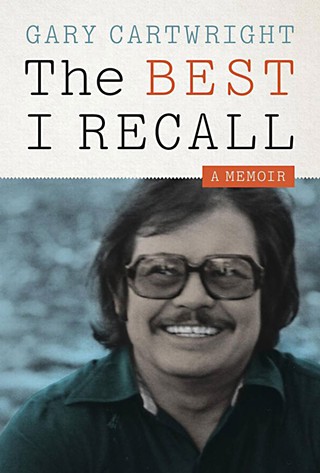

Thus begins Gary Cartwright's 1976 Texas Monthly profile of the state's most notorious stripper, a story that in many ways cemented a style of inserting himself into the narrative. It's a technique that served him well in writing the memoir The Best I Recall (University of Texas Press, 272 pp., $27.95) When UT Press asked him to pen the book, he realized details of events from party days of yore were often hazy.

"Even though I wasn't the topic I was writing about, I wrote in first person a lot," Cartwright, now 80, said recently from his Central Austin home. "So I could go back and re-read stories from Texas Monthly and other magazines and get a timeline of what I'd done and when I'd done it. I put it together by going to school on myself."

Cartwright had a longstanding desire to meet Candy Barr going back to his Army discharge when a buddy and he showed up in Dallas at Abe Weinstein's Colony Club with a bottle of whiskey in the days pre-liquor-by-the-drink. They weren't (yet) drunk, but an overzealous cop threw them in jail anyway. Candy Barr had to wait.

Barr had quashed previous attempts to interview her, including one by the famed writer Gay Talese, but Cartwright knew a stripper named Chastity who knew Candy. "She was beautiful, she was famous, she was mysterious, and nobody had written about her," he says. "I would follow her around the house and try to interview her. It was going nowhere. A couple of times I thought, 'Screw this. I'll just leave.' But I didn't. So I wrote about experiencing Candy Barr. That's one thing I learned. You have an idea of what the story will be, but it doesn't work out that way. There's still a story there. It's another story, and it's probably as interesting or more interesting than what you've conceptualized."

Cartwright's life swirls in the interesting. The memoir cuts it into four distinct chapters: the early Mad Men-esque years in the Metroplex newspaper game, the drug-hazy Seventies, the Texas Monthly years, and the final truths/sadnesses of growing older. Underlying themes run through it: an ability to be in the right place at the right time surrounded by the right people, a rage against the humdrum life he saw others leading, and a churning battle with the belief that he somehow didn't deserve it all.

"That's probably a reflection of my character that seeps out," he says. "You don't know what you're doing, but you know that if you keep doing it, it'll work. There always comes a time in a story, whether it's a magazine story or a book, where you realize you're on to something. Most writers I know had a plan, but I never had enough foresight to have a plan."

Credit the original spark to Emma Ousley, a journalism and English teacher at Arlington High School who made her students free-write to start every class. "People said, 'Write what?' She said, 'I don't care. Just write.' I wrote. I thought, 'This is great.' I would write a sentence, then I'd write another sentence. It was great fun." One day Ousley pulled him aside and pointed out his writing talent. "It floored me," Cartwright says. "Nobody had ever felt I had a talent for anything."

As a Fort Worth Press paperboy, Cartwright became a fan of Blackie Sherrod, a newspaper columnist and sportswriter. After a stint as a Fort Worth Star-Telegram cops reporter and an ill-advised stretch in advertising, Cartwright landed under Sherrod's guidance as part of what would become an all-star sportswriting team. Sitting across from him were Bud Shrake and Dan Jenkins.

Sherrod "took us under his wing and taught us how to be newspapermen, not sportswriters," Cartwright says. "Sportswriters tended to be what we called homers. They think of the home team as being we, part of our family. If you're a newspaper guy, you think objectively. That attitude changed over the years partly because of writers like me, Jenkins, Shrake, and particularly Blackie."

The sports team also embraced a hard-partying lifestyle with lots of booze and lots of women. "That's how everybody I knew lived," he says. "Everybody I knew was divorced, so when I got married for the first time, I think I figured in seven years I'd be divorced, and I was."

He ended up sharing an apartment with Shrake just north of downtown Dallas where, when the bars closed, late-night parties percolated. A regular houseguest was a flame-haired stripper named Jada who worked in one of Jack Ruby's clubs. "She was a wild woman," Cartwright says. "She had long, long fingernails. She was a cat woman. She wasn't much of a dancer, but she was fairly sensational. She'd hump on a tiger skin rug." Ruby would show up at the apartment looking for her, usually armed. "Ruby loved Jada, but he hated that act. She'd tell him to go screw himself."

Later, Cartwright, now remarried, joined Shrake in waving to President Kennedy's motorcade moments before JFK was assassinated. The sportswriters were in Cleveland for a football game that the Dallas Cowboys inexplicably agreed to play the following Sunday, the day Ruby shot suspected assassin Lee Harvey Oswald.

"I've never been through a time like that," Cartwright says. "That's why it was so stunning that the Cowboys played a game that Sunday. Nobody wanted to play a game. Nobody wanted to watch a game. Everybody just went through the motions."

Cartwright's second wife, Jo, had purchased a convertible in Ohio, and the two drove back to Dallas via Nashville. "We were in no hurry to get anywhere," he says. "The world had just stopped. Everybody felt like something else was about to happen. This was the start of a revolution – something. An unnamed thing that couldn't be good. Life continued, but it would never be the same."

Shrake triggered a change in Cartwright's career path. He and Jenkins both headed to New York City to write for Sports Illustrated, and Cartwright followed as a freelancer. Jenkins, whom Cartwright considered the best pure sportswriter he'd ever met, had branched into fiction with Semi-Tough, a rollicking comic novel about pro football starring Billy Clyde Puckett, a character he'd created for column fodder back in their newspaper days. Shrake was even more serious about writing fiction.

"Everybody admired Bud," Cartwright says. "He was a big guy – 6'6" – and very dynamic. He was a natural liar. He always knew he was going to be a novelist. I just sort of followed his lead."

Shrake advised him to just write one sentence at a time, so Cartwright sat down and did just that. The result was 1968's The Hundred-Yard War. "I thought it was going to be about pro football because that's what I knew," Cartwright says. "I'd covered the Dallas Texans (now the Kansas City Chiefs) and later the Dallas Cowboys. So I wrote a sentence. Then I wrote another sentence. A story developed." His main character was modeled after charismatic Cowboys quarterback Don Meredith. The coach was originally a take on Cowboys coach Tom Landry, but Cartwright found Landry too enigmatic to grasp and went instead with a Vince Lombardi-esque coach whose explosive, egotistical personality was more fun to put down on paper.

"It taught me I could write a book," Cartwright says. "Later, there were a lot of things I'd wished I'd known beforehand. I would have restructured the book or dwelled more on certain characters and less on others. But there's no way to write than to sit down and do it."

An editor talked him into penning a second novel, Thin Ice, set in the world of hockey, a sport the Texan knew little about. "They offered pretty good money at a time when I needed money, so I said, 'Sure,'" Cartwright recalls. "To solve the problem of not knowing anything about the game, I made my lead character a goalie, thinking that at least he'd stay in one place. I also decided he'd be going blind."

Shrake and Cartwright were dreamers and provocateurs prone to dressing up in capes as the Flying Punzars, a supposed foreign circus act. During a road trip, they only half-jokingly talked of producing their own movies and publishing their own books, and thus created Mad Dog, an actual corporation whose motto was "doing indefinable service to mankind." Cartwright calls it the "world's longest practical joke."

When a Western screenplay of Shrake's called Dime Box was being shot in Durango, Mexico (as Kid Blue), Mad Dog showed up with a Winnebago and a smaller van festooned with Mad Dog Productions banners. Dennis Hopper starred as an outlaw trying to go straight. "He was totally crazy at the time," Cartwright says. "He had just come off Easy Rider, which was a huge success. He was a movie star in a day when movie stars had just about ceased to exist. He played the role. He was a pain in the ass, but refreshing." Hopper was soon inducted into the membership of Mad Dog.

As part of their corporate activity, Shrake and Cartwright filmed a fake movie-within-a-movie titled The Congressman's Carrot, a joke that involved Cartwright pulling back his jacket to reveal a carrot in his vest pocket. The craziness hit its crescendo at the New Year's Mad Dog Masked Ball where a crowd including writer Peter Gent (North Dallas Forty), actor Warren Oates, and Don Meredith mingled and partygoers sampled vanilla-flavored LSD and, as concocted by Cartwright and his wife Jo, marijuana cookies that packed a 12-hour punch. Meredith and his girlfriend, unaware of the secret ingredient, were wolfing them down.

"Life was really boring back then," Cartwright says of Mad Dog. "Nobody was taking chances. Nobody was pushing the envelope. I wanted to make things happen. One way was to be as outrageous as we could and see where the chips fell."

Cartwright said his life's third act was a "lapse into journalism."

"Fact and fiction come together," he says. "There's a narrow line. My first two books were fiction, so I taught myself to write while writing fiction. Texas Monthly came along, and I got into long-form journalism. I really liked that and understood it because I'd written long-form fiction. I'd learned to trust my instincts. You learn by doing. You learn by failing. You learn by trying."

Crime quickly became Cartwright's forte. His tale of Dallas businessman Cullen Davis' trials for murder grew into two Texas Monthly pieces and the 1979 book Blood Will Tell, which was then made into the TV movie Texas Justice. Convicted cop killer Randall Dale Adams wrote to Cartwright from death row. Cartwright's Texas Monthly piece and Errol Morris' 1988 documentary The Thin Blue Line led to a reversal of the conviction. "The cops had stacked the deck against him," Cartwright says. "They had an unsolved cop killing, and he fell into their hands. I didn't particularly like Randall Dale Adams. He didn't have a personality. He's not the guy you'd like to have a beer with, but I thought he'd gotten screwed over."

Cartwright knows that some folks think of him as "that wild man, that crazy man," but the frivolity has been tinged with its share of sadness. He reconnected with his son Mark when the boy came to study at UT. They became more like friends than father and son. Mark called his father Jap, a nickname from his Fort Worth Press days. Then in 1996, Mark was diagnosed with leukemia. "He was so tough and resilient," Cartwright says. "I thought he'd come through it, but he didn't."

By his side through it all was Phyllis, the wife who stuck. Cartwright's first two marriages were short and fiery – he admits in the book to hitting each of his first two wives in the jaw – but Phyllis was the one. They had plans to celebrate their 30th anniversary in France when she was diagnosed with cancer and died in a few months. Cartwright later remarried, but his wife Tam also died of cancer.

"You go on living," he says. "You do the best you can. I've always had an upbeat attitude. I don't dwell on what I can't change."