Father Time

Claude van Lingen's conceptual artwork counts down from 1,000

By Andy Campbell, Fri., Dec. 20, 2013

Even for Co-Lab's ever-mutable Project Space, this was a dramatic installation: dozens of narrow boards, each with one mirrored side, dangled from the ceiling as four high-power projectors threw live feeds from popular news channels: FOX, CNN, HLN, MSNBC. The finely styled coifs and visages of news anchors refracted endlessly off the spinning mirrors, at times transforming the simple four-walled space into an impossible maze. Here was Jane Velez-Mitchell (or was it Greta van Susteren?) informing viewers that New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie's bid for re-election resulted in a landslide win, and there was Anderson Cooper warning of Syria's stockpiles (or was it the Nashville plane crash?). On one wall, a pundit speculated on Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius' imminent testimony before Congress, effectively channeling a nation's frustrations with the Healthcare.gov website into wild gesticulations. The word "Luddite" was used.

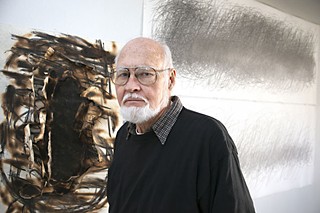

For most of us, it's not news that we thrive on a daily dose of echo-chamber informatics; but knowing it and feeling it are two different things. In this funhouse of media – more horrorshow than pleasure palace – entrapment was the dominant affective mode. Amidst the visual and sonic cacophony, septuagenarian artist Claude van Lingen calmly snapped pictures of his installation. Slightly bent over yet still a commanding presence, van Lingen had, in short order, made an incisive critique of contemporary media and politics with his installation 1000 Years From Now, Now, Now, Now, Now. ... ... .... Said one of Co-Lab's gallery assistants, "I can never stay in here for very long."

How is a length of time measured and crystallized as form? This is a key concern in van Lingen's diverse artistic practice, where timescales dip into millennia, layers of graphite and paint accrete like geological strata, and the performance of drawing is an integral part of the final product. Van Lingen's life and career trajectory, from South Africa to New York to Austin, traces a line of influence that, while not yet widely acknowledged, is certainly felt in the corridors of art-school pedagogy and in the reverential reflections of his students and family. Still, he cuts an odd figure in an Austin arts landscape peppered with young MFAs and post-MFAs, not least because of the seeming paradox between his advanced age and a diamond-sharp conceptual schema.

'It Was Incredibly Lonely'

As police opened fire on the thousands of protesters in the township of Sharpeville, South Africa (eventually leaving 69 people dead, including women and children), they were perhaps unaware of how their actions would catalyze an international response to the 12-year-old apartheid government – apartheid being the systematized segregation and resettlement of, and state-sanctioned violence toward, non-white South Africans, largely instituted by an Afrikaner ethnic minority. While the fallout from the 1960 Sharpeville massacre most prominently resulted in the levying of economic sanctions and boycotts from European and African nations, artists and cultural producers living in South Africa felt its effects most acutely in the (in)accessibility of experimental and conceptual art from Europe and the Americas. Paul Stopforth, who teaches at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and one of van Lingen's former students at the Johannesburg College of Art, remembers, "We never got to see the real thing. We only learned through reproductions and slides." Except for the odd exhibition or a once-in-a-lifetime lecture by modernist critic Clement Greenberg, the embargo was absolute. Students, then, had to learn about contemporary art from their teachers. Another one of van Lingen's students during that time, Trevor Gould, who is now professor of sculpture at Concordia University in Montreal, Quebec, admits, "It was incredibly lonely. There was nothing like making a sculpture that had a rapport with what was going on in Europe and knowing that you were, in some senses, sitting alone in South Africa." Van Lingen cut this isolation for his students, exhibiting works that were as experimental as he was asking them to be. "There was a lot of respect given to him by young students like myself." Says Stopforth, "It was very much by example that Claude influenced us."

At the time of the Sharpeville massacre, van Lingen was on sabbatical in Paris from his job as a high school teacher in Meyerton, only 20 minutes from Sharpeville. By 1965, he became chairman of the Teacher Training Department at the Johannesburg College of Art. In his 13 years at JCA, van Lingen consistently clashed with faculty members who, while they seemingly embraced newer abstract styles of painting, only did so under the guise of reinforcing Afrikaner nationalist and normative notions of family and politics. Van Lingen couldn't have been farther from such positions. While he does have Afrikaner ancestry, his family "was Anglicized around the turn of the 19th century." Says the artist, "They were drillers for water in the mines, and I went to English boarding schools at convents all of my life. My mother was a single mother. So I felt more English than Afrikaner." Gould confirms that English-speaking South Africans like himself "were automatically consecrated as liberals, but for Afrikaners it wasn't so clear."

During these tense years in South Africa, van Lingen didn't remain artistically aloof; it was only a short time after the Soweto Uprising that van Lingen began to make preparations to leave Johannesburg for New York City. "I'm very concerned about this little Earth and all the troubles that go on here," says van Lingen, "because of the political situation in the country and the school, I got out of it. I moved to New York to get my MFA at Pratt."

At the time of van Lingen's move, the artist was making "flexibles," large sculptures made from different colors of polyurethane foam. Unaware of continental sculptors such as John Chamberlain, who were conducting similar (but smaller-scale) experiments in foam, van Lingen began to investigate principles of balance and body through industrial material. Splayed open or stuffed into Plexiglas vitrines, van Lingen's flexibles were programmed into the 1975 São Paulo Biennial. Installation photographs of this international exhibition show van Lingen's work, bright and bubbly, effervescing against a mostly drab room hung with abstract work. The sensual pleasures of the flexibles are aptly described in a contemporary review of van Lingen's work: "Foam bulging through a wire mesh invites prodding; curving and swirling, interlocking and hanging foam forms provide a strong visual pleasure."

Creative Thinking and Teaching

Because of their cost and shelf-life ("the damn things wouldn't last for more than a month."), van Lingen abandoned the flexibles on his move to New York. It was there that he began a new series of works, "1000 Years From Now," inspired by a trip to Pearl Paint on New York's bustling Canal Street. Sizing up the various manufactured paints for purchase, van Lingen wondered, "Well, OK, if I take the cobalt blue from six manufacturers and I paint them in panels next to each other, would they be the same?" Fueled by this line of inquiry, "The question came as to whether this would be true for the next 100 years, or 1,000 years from now." And so began van Lingen's earnest engagement with longer timescales – encompassing many tens of generations.

Van Lingen was, in fact, putting his own pedagogy into practice. As part of the foundations faculty at the Johannesburg College of Art, he had developed a course in "creative thinking" titled Perceptual Studies. Inspired by discussions with artist, designer, and architect friends, and Alex Osborn's Applied Imagination, this course sought to teach students technique alongside a learned and sustained curiosity about meaning and materials. Gould remembers one exercise where students took a 2' x 3' piece of board and placed stuffing atop it in mounds, covering it with canvas, "so you could draw parallel lines on this irregular surface and understand how line created form." But this was only the first in a multi-step process through which students "arrived at some smart and interesting works. They were flat, didn't have any representational content, but they existed as paintings. It was interdisciplinary, although we didn't use that word then. And perhaps more meaningful because of that." The purpose, for van Lingen, was always to give students a better insight into what kind of artists they could be: "Early on, I asked students to bring to class an object that they liked or disliked, and then they subjected these objects to three or four months of intense visual analysis." He adds, "Through many processes, including research, we got a gestalt. At the end of class, I presented the students with what they had created, saying 'This is you. You've got to know yourself and find your passions.'"

While in New York, van Lingen worked a day job for Scholastic Corporation and was beholden to the fickle fates of the publishing industry. "When a popular series was canceled, Scholastic would fire a bunch of employees; such was the case when Goosebumps was canceled in the 1990s and 400 employees, including me, were fired." Hired back soon after by an art director, van Lingen's tenure at Scholastic ran until the final installment of the wildly popular Harry Potter series was imminent. Says the artist, "I just smelled it. And my lady friend at the time was moving to Austin, and I decided I'd move with her." This turned out to be a prescient move, as the night of his farewell party in New York, the art director who once had saved van Lingen from unemployment approached the artist with the news that he had just been fired.

1000 Years From Now, Now, Now, Now, Now. ... ... ...

The BBC call-in radio show World Have Your Say is on when I visit van Lingen's home on a quiet street. Work created in the almost 60 years that the artist has now been active peppers the walls, leaving few empty spaces. Gigantic process-oriented drawings – where bits of graphite have gently rained down a sheet of paper evincing rainclouds and the scrim of attendant raindrops – hold court next to brightly collared paintings – the number 1,000 resting scumbly atop all previous integers. It is clear from such obsessive and rigorous work that the eureka moment van Lingen had on Canal Street in 1978 continues to drive his practice.

A series of 15 slim, horizontal paintings are perhaps van Lingen's finest examples of this series. Each canvas is divided into 1,000 squares, each designating a year continuing forward from 1986. For every new year, the artist buys a pre-designated manufactured color paint, and applies it in the appropriate year's square. Thus far, only 28 of the 1,000 squares have been filled, and looking at the canvas it's easy to be overwhelmed by the enormity of the conceptual task van Lingen has lain out for himself.

Ah, but here's the rub: Van Lingen's granddaughter, Meghan McKnight, who lives only a few streets away from the artist, has begun to take up her grandfather's mantle. Raised in Johannesburg and Cape Town, South Africa, McKnight only saw her grandfather "every couple or few years. When he visited, he would show us his drawings, and because I was interested in art, he would give me tips on making work." Moving to Austin in her early 20s, McKnight started to help van Lingen in 2007. "He initially showed me how to paint the different blocks," says McKnight, "but after a couple years of helping him do this, he told me, 'Eventually you'll need to carry on doing this after I pass.' It's something I'm happy to carry on and hopefully pass on to my children."

Van Lingen's thousand-year gambit is not merely a conceptual gesture, but rather an expressed need for continuity beyond the span of a life. While the works often look systemic and cold, their need for maintenance is all too human. They age, sometimes poorly; they need care, sometimes mind-numbingly specific; and they persist, paradoxically shifting and constant. In van Lingen's life and work, says Trevor Gould, "It was about feeling like an artist. You can go through training, you can learn all kind of techniques, but feeling like an artist ... now that is a different proposition."

"1000 Years From Now, Now, Now, Now, Now. ... ... ..." is on view through Jan. 4, Wednesdays, 5:30-8pm, and by appointment, at N Space, 905 Congress. For more info, visit www.co-labprojects.org.