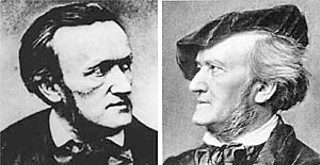

When Wagner Became WAGNER

How 'The Flying Dutchman' made opera bigger than big

By Jerry Young, Fri., March 26, 2004

The name Richard Wagner brings to mind massive stages crowded with massive singers and orchestras that overflow the pit. There is a word for this scale: Wagnerian. This week, Austin Lyric Opera is staging the first opera by the composer for which that term fits, The Flying Dutchman.

Wagner wrote three operas before Dutchman, but today only part of one – the overture for Rienzi – has any presence in the repertoire, a telling testament to their quality. The Flying Dutchman, composed in 1841, was a turning point for the composer: the first time he incorporated into his operas universal themes and monumental characters from Germanic lore and mythology.

The use of myth was not new; opera got its start retelling classical myths and histories. But Wagner moved the action from Mt. Olympus to Valhalla, and Wagner's Dutchman is set adrift off the coast of Norway rather than in the Aegean. The old Germanic fable of an ancient mariner condemned to wander the seas forms both the basis for and the centerpiece of Wagner's work. "It contains in a nutshell all of the musical material and the whole story for the entire opera," says professor John Weinstock of the Department of Germanic Studies at UT-Austin. Wagner also lets his audience hear the story in a setting in which it was passed down for centuries: as a ballad sung by the heroine Senta to a room full of women spinning and waiting for their sailors to return.

And the old tale the spinners hear is this: A Dutch sea captain once swore during a terrible storm to round a cape if it took all eternity. Satan took him up on the wager, and the Dutchman was damned to sail the seas forever. "She sings herself into a trance," Weinstock says. "In the third verse, she tells how the Dutchman can be redeemed. She is exhausted, and the girls start singing the refrain. Senta jumps up and says she will be the one to save the Dutchman."

With that ballad, Senta becomes Wagner's first archetypal redemptress, the proto-Isolde, Brünnhilde, and Kundry. "The Dutchman and Senta are the first Wagnerian heroes in that they represent the fundamental human lot, and that is isolation," Weinstock says.

As his operas become sagas of transformation, Wagner is himself transformed from an ambitious young composer with few successes into the master builder of music-dramas.

While operas such as Tannhäuser and Parsifal and the quadrilogy The Ring of the Nibelungen are long enough to keep operagoers up past midnight, the underlying story of them all can fit on the back of a business card: A flawed hero struggles for redemption that can be granted only with a leap of faith by a redeemer. Weinstock points out, "The redeemers are mostly women, and the redeemers long to redeem as much as the sinners long for redemption."

In latching on to such profound themes as alienation and redemption to drive the music and drama, Wagner became a force who still has to be reckoned with, casting a long shadow in art and culture (he was Hitler's favorite composer). He became Wagnerian. "All of this stuff we find in the later dramas parallels Wagner's own life," Weinstock says. "The two and a half plus years he spent in Paris were a disaster, but that made him a composer – a spiritually nourished artist redeemed by the good angel of music."

What was that misdeed for which Wagner had to atone? Aiming too low early in his career and failing, Weinstock says. "It was his bid to have the same kind of success as Meyerbeer in Paris. The operas are allegories, and Wagner identifies with the Dutchman as a symbol of the alienated artist seeking redemption for the consequences of his foolhardy transgression."

True redemption doesn't come easily for the Dutchman, Tristan, Siegfried, Parsifal, or Wagner, just as Tolkien couldn't have made his point if he had made his ring story as short as, say, The Hobbit. Wagner needed a large stage and plenty of time to accommodate the glacial turning radius of themes as massive as alienation and redemption.

Garnett Bruce, who directs ALO's production, says that sustaining that tension is central to making Wagner work. "It requires you to become at home with a metaphor for a very long time and, in our fast-paced, 30-second-sound-bite world, takes some discipline," Bruce says. "Because we are not given to sudden lashes of transformation, the moments of greatest passion always have to be moments of great stasis in the visual world."

Bruce says Wagner's Ring is his first choice for those daylong drives through the flat expanses between Dallas and Santa Fe. "If you start Das Rheingold when you leave Dallas, you hit act two of Die Walküre when you hit the New Mexico border. It is great music for long journeys, where you get to think about long moments. It is music that helps take you across time zones. Wagner was beginning to experiment to make opera a theatre of ideas."

For Wagner, ideas are represented by those meaning-packed leitmotifs that sometimes inspire and sometimes harass the singers around the stage, but always interact with each other to tell in music the story that unfolds on the stage. "It is not as mathematical as Bach or as measured as Mozart, but he resets form from its very foundation. He takes a long time to go through all of the possible variations, and that evolution is what appeals to the German mathematical mind – that desire for structure and form. That is why some people love Wagner and some people hate him."

Because the characters are transformed through self-mastery, the performance can't yield to emotional temptations, even though the orchestra wails with anger, love, lust, longing, dread, and remorse. While the tremors are felt throughout the musical score, the singers have to stand there, take the hard blows, and hold back. "Wagner was wrestling with opera's sentimentality and emotionality, but he was trying to be a little more clinical. You put all of your passion into the motif and let the orchestra register those flags, but you don't let the heart out onstage," Bruce says.

So in The Flying Dutchman, as in the later operas, arias become obsessive moanings over the character's fate. Weinstock calls them "monologues of exhaustion." "In all of these monologues, you've got the plight of the hero alternating with some hope of alleviation, but usually ending in despair. The Dutchman's lament goes on for about 15 minutes in a relatively short opera. He is doomed. He has no psychological depth." He is alienated, even from his audience. "He doesn't have a name – he is just called the Dutchman. The audience doesn't sympathize with him; we sympathize with his predicament."

The elemental story that drives the opera drives Bruce's staging. "Most importantly, I want people to understand the legend," Bruce says. But he also speaks of the rare chance this production offers. "There is nothing like hearing an orchestra playing Wagner in the same room with you. No CD or sound system can reproduce it. We trumpet the new Dolby sound system in theatres, but there is a limit that hearing music in a movie theatre can't cross. We can make it louder, but we lose the nuance and complexity you can hear in a big hall." ![]()

The Flying Dutchman runs March 26-29, Friday-Monday, at Bass Concert Hall. For tickets, call 472-5992 or visit www.austinlyricopera.org.