An Eye for History

By Sam Martin, Fri., April 23, 1999

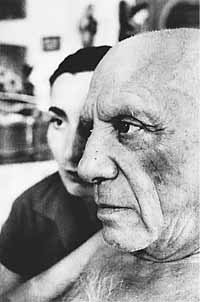

The year is 1958. The place: La Californie, Pablo Picasso's village chateau outside Cannes, France. David Douglas Duncan, the celebrated combat photographer and Life magazine photojournalist, is working late. He takes one of the canvases belonging to the artist, dusts it off, situates it in front of two huge copy lights, and shoots a photograph of it with a silent-shutter Leica camera. In fact, the only sound echoing through the open-air building is the dab and whisk of Picasso's paintbrush in the room across the hall. Then something bad happens. Duncan takes a charcoal drawing, dusts it off like all the rest, sets it in front of the copy lights, and shrinks back in horror. Not only has he smudged a work that was created by a dear friend that happens to be the greatest artist of the century, but also he has smudged an artwork that until then no one outside La Californie had ever seen. Duncan had been photographing Picasso's personal stash.

At 76, Duncan, who still lives in the south of France, tells this story with the same mischievous grin and sparkle in his eye that he must have had when he was 30. He leans across the table excitedly, talking with his hands while sailing through an encyclopedia of long, rich memories. Not a detail escapes him. Not the smell of breakfast that next morning in 1958 when he forced himself to tell Picasso about the smudged bungle or the quality of the tense silence that followed before his friend shrugged it off as a necessary twist of fate. In fact, as I sit listening to Duncan at the LBJ Library, where the University of Texas is displaying "David Douglas Duncan: One Life, a Photographic Odyssey," the exhibit drawn from the archives of Duncan's life's work which were recently acquired by UT's Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, I realize that the 400 photographs, letters, cameras, and Picasso sketches that make up those archives are inextricably linked to the man who took them. Before there was a photograph, there was a man and his camera.

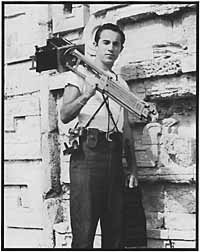

Born in 1923 in Kansas City, Mo., Duncan became one of the most accomplished and prolific photojournalists of the tumultuous 20th century, taking part in every major military conflict from World War II to Vietnam. He was on board the USS Missouri during the Japanese surrender. He was the first Westerner to photograph the Russian treasures inside the Kremlin and the first to introduce the West to the Nikon camera. In the Forties and Fifties, he worked for Life magazine. He captured the British departure from India and the birth of the Israeli state. He has photographed Bassari warriors in Africa, Russians in Afghanistan, and Democrats in the United States. He shot Ava Gardner in Paris, Nixon in Bougainville, Eisenhower in Guam, and, for 17 years, Pablo and Jacqueline Picasso in the south of France. He has produced 27 books, including the 1966 autobiography Yankee Nomad, and now the Duncan Endowment for Photojournalism at UT, a fund initiated by Duncan when he returned the $100,000 fee offered to him by the Harry Ransom Center for his archives. The list and the legend keeps going.

Even so, with such a variety of worldwide subjects at the end of his lens, Duncan is best known for his harrowing and heroic accounts of young U.S. Marines at war. By assigning himself the most forward position at every opportunity, Duncan not only captured the fatigue, the tragedy, and the resilience of the human spirit in the men on the battlefield, but he also managed to miraculously escape personal injury and his own death over and over. In fact, one account of Duncan has him waking up in a bunker one morning, standing up to stretch, and getting hit in the chest with a machine gun bullet. The only reason he lived was that the bullet was at the end of its range and it simply ran into him and fell to the ground without so much as tearing his Army-issue camera vest. Who says some things aren't meant to happen? By the way, the charcoal drawing: It hangs to this day -- smudges and all -- in the Picasso Museum in Barcelona. It is, as Duncan likes to say, "the only Duncan-Picasso in existence."

Austin Chronicle: Did the bomb and Hiroshima change the war for you?

David Douglas Duncan: Hell no, we were thrilled. I was in the Philippines. In fact there's a photograph here at the museum of an extraordinary event that took place right before Hiroshima. It's of a Japanese officer in a B-25 American bombing plane. Now, that's the act of treason, and, as far as I know, the act of treason has never been photographed. This Japanese officer walked into the American lines in Mindanao and said, "I want to bomb my own headquarters, I hate them." So they debriefed him for two days, assigned a huge attack force, and bombed the Japanese headquarters. That night was the report from Hiroshima. The huge news was this incredible weapon. I remember we were sitting there just after having whatever rations we had. We heard it and everybody just went through the roof. I thought it was great. It was the end of the war.

But you have to remember, back then there was no knowledge of radiation or aftereffects, and no one thought in compassionate terms of how it destroyed an entire city. Although I must confess that I wrote to my mother and father that night and I thought about the city. I wrote, "Jesus, someplace there's someone like you and mother at home far away from the war and you got hit. That's the same as these families in Hiroshima." I feel very proud of myself for feeling a sense of anguish that that should happen to innocent people. You can't hang the brutality of it on the American troops or the Japanese troops or the Germans. You can't hang it on everybody. Nobody knew.

AC: And then not long after that you were on board the USS Missouri, where you witnessed the Japanese surrender.

|

|

AC: So once you got on board the Missouri, what was the atmosphere like?

DDD: Well, I'm from Kansas City, so it was very symbolic for me to be on the Missouri. The press had been clamoring to get on board. I didn't have any press credentials. I was a Marine lieutenant in the Marine Corps, and I was a combat photographer for the Marine Corps. By a fluke, when I went overseas for the first time from San Francisco in late '43, I went out on the Essex, sailing to Hawaii, and I ran into the photographic officer on board and he had been with Eastman Kodak. I knew the guy earlier. He said, "Oh, Dave, do me a favor. I've got an executive officer here named Fitzhugh Lee ... " -- handsome fella, but he was really tough -- "Do me a favor, shoot a portrait, and maybe I'll make your life easier." So I shot a portrait of this very handsome, austere man -- he was a relative of Robert E. Lee -- and it turned out to be very dramatic and a very good portrait. I gave it to Fitzhugh, but he didn't thank me very much. Three years go by and I run into the chief photographer for Life, and I was trying to get aboard the Missouri. He said, "Dave, there's just no chance at all. There's the handsomest, toughest guy running the thing." I said, "Is his name Fitzhugh?" He said, "Yeah, sure. Where'd you hear about him?" So he took me up to the ship.

I was up on this five-inch turret looking down, and it was the best position on the whole battleship. Here comes the Japanese, Shigemitsu, and right below me, the door opened and MacArthur stepped out, and Stillwell and Admiral Nimitz. Right below me. I had a Leica and Rolleiflex and I was shooting right straight down. It's in the museum here, a color print of the signing ceremony, and it's sort of a landscape of tranquility. There wasn't a sound on board the ship except when Shigemitsu came aboard, and he had a terrible time getting up the ladder. He was in black-and-white mourning clothes, limping across the deck of the battleship because he'd lost a leg in the war with the Russians in 1905, I think it was ... a famous incident. He was terribly handicapped. I felt really embarrassed that nobody went forward to help him. I tell you, he had a hell of a time. The Japanese were too proud. And so were the Americans. Here were twoformer enemies facing each other and the only sound was Shigemitsu limping across the deck to the signing table to surrender for his country.

AC: So now WW II ends and you head back to the states and in 1946 you get the job at Life magazine.

DDD: Yeah, well [Jay] Eyreman -- the same guy who told me about Fitzhugh on the Missouri -- was the chief photographer for Life and he said, "Look, Dave, when you get back to the States, come and see me in New York and maybe you can get a job at Life." Well, to get a job on the Life staff at that time was celestial. You were really in orbit. Well, I did happen to get to New York and I did go in to see Eyreman, and he said, "Dave, play it cool. All the guys are coming back from overseas and their wives are threatening them with divorce if they go overseas again." And Hicks -- Wilson Hicks, a legendary tough guy who ran the shop with an iron hand -- needed someone to go to Persia because the Russians were coming down through Azerbaijan, Iran, by this time, and he wanted to get somebody to cover the Russian invasion of northern Persia. I walked into his office and this very elegant man with slicked-back hair and glasses just sat there watching me with a noncommittal look, and I made my presentation. I was still in a Marine Corps uniform.

AC: And at this point you were still not affiliated with the press.

DDD: Not at all. I was a graduate of marine zoology at Coral Gables, Florida. Before that it was archaeology, geology, and Spanish at the University of Arizona. I accidentally got into photography. I came back to Life at that time with the only credentials of selling stories to the Sunday rotogravure sections for three dollars apiece -- stories I made catching rattlesnakes or deep-sea fishing or quail hunting in Missouri. I had two stories working for National Geographic, which to me was big time. One was catching broadbill swordfish off South America -- Peru and Chile -- and one was catching the giant green turtle off the coast of Nicaragua between the Cayman Islands. When I went to Grand Cayman from Key West in '39, it took five days on a schooner and that was the center of the turtle fleet. It was a job that the Geographic got photographing for an exhibition at the Museum of Natural History in New York. That's all I had when I went to Life. That and the Marine experience. Anyway, after my presentation, Hicks said, "When can you get out of uniform, because you're our newest Life photographer. Can you be in Persia this weekend?" And that was it.

AC: So I've always had a vision of Life magazine in the Forties with the reporters running around with fedoras and press cards stuck in their brims. What were the offices like back then?

|

|

DDD: No, never, never. Life photographers were all of international origin. Albanian, Latvian, Russian, German, French, and there were very few native-born Americans. Now, nobody ever wore a press thing in his hat ever, ever, ever. First, you walked right in. You didn't need any identification. You introduced yourself as a Life photographer and every door was wide open. It was before television. Look, my starting salary was $9,000 a year. My finishing salary after 10 years was $12,000, and I'd done everything all over the world. Nobody ever really shot for money. We shot for the joy of it and the competition of it and the creativity that was involved, and we would fight mano a mano with any other photographer for the space for the story until the moment the story was published. Then we were all so proud of our colleagues' pages. There was a real pride of comradeship. There was never any indication that we were from the press.

AC: During this time, you had traveled all over the world ...

DDD: Except the United States. In '68, I came back to shoot the [Democratic] Convention.

AC: Did you ever get tired of traveling?

DDD: Never. I drive my wife crazy today. A friend of mine came down last night from Kansas. I was so jealous, I wanted to go back with him in the car to Kansas City. I'm happy in many ways, but I'm really, really a nomad.

AC: Then you eventually meet Picasso. What an amazing man he must've been. I read somewhere where he worked all night the night before he died. Was he always creating?

DDD: Always working. He was generous, funny, tough, working, and he loved his work. The work was everything. You don't understand, the work was everything. He was the most courtly man you can imagine, a real Spanish caballero. The false stories that some of these ill-informed biographers ... Hell, I was at his side on and off for 17 years, all the time, all the time, and I saw him in the presence of many, many ladies, and I'm damn good with my eyes, I can tell you. I can really see things. I never once at any time in my life with him intercepted a look that was in any way other than courtly.

AC: Was he a quiet man?

DDD: It depended on the situation. He was a gregarious man who forced himself into professional retirement and isolation so he could work. He always said, "The trouble is, they're so nice and I'm so bad, so I'll lock the door." If you came to him right now from Austin, he'd lean forward, look you right in the eye -- his eyes never strayed; none of this looking around the room to see who's recognizing Picasso. Baloney! -- he'd say, "Tell me about your work, tell me about Austin, tell me about you."

In many ways, we who knew him were his antennas to the outside world. We picked up stuff and transmitted it back to him, through our eyes and our stories. Still, there was never a time that I was sure that I was focused on where he was. I saw it happen time and again. He'd be attentive and ask me about my trips to Russia or to Vietnam. One time I came back, he was having his tea at about 9:30 in the evening and I said, "Look, I came back through St. Petersburg and I went to the Hermitage and I knew one of your works was there, but I couldn't find it. No sign, nothing for kids, no posters, nothing." I said, "You know something, Maestro, the Russians don't deserve you" -- because, you know, Picasso was a communist from the Spanish Civil War when they were fighting the fascists in the streets of Barcelona in '39 -- and he looked at me and said, "Oh, Ishmael" -- he called me Ishmael, not David -- "I'm only a little communist. Understand me." It was the only time I ever discussed communism with Picasso.

The point is that if you would come, he'd look right at you and listen to you and probe you without blinking. He never blinked. I asked him once why he never blinked, and he said, "Why blink?" Not like Nixon, who was a consummate blinker -- like a machine gun: blub, blub, blub.

|

|

Keep in mind, I was not a very prepared presence in that household, but that was my saving grace. I was not an art professional. But as time went by, I sure learned. After about two years, Picasso came to me and said, "Do you want to meet some of my friends?" And he opened the door and there were paintings stacked to the ceiling. I took the next year and a half to photograph them. I was uneducated and inexperienced and I had this stuff in my hands. I had more pictures in my hands by Picasso than any expert in the world. Day after day after day. He'd be painting in the next room and I'd be photographing against a backdrop bedroom with huge copy lights, and he'd be taking a break and walk in and say, "What's the matter, Ishmael?" and I'd say, "I have no idea what I'm looking at," and he'd tell me. I had Picasso explaining his paintings to me.

AC: The Vietnam War came around and Vietnam was different ...

DDD: I'd been there before that, when it was Indochina, in '51, again in '53. I'd been in Korea in '50. I did a story on Indochina called "Indochina All but Lost," which was nine months before Dien Ben Phu. I was persona non grata both with the State Department and with France, and with my employer, Henry Luce. I told my employer, "If you don't like it, then go ahead and fire me." But Life magazine was correct. I said Indochina was lost. Federal policy said that Indochina would be saved by French policy, and I came in and shot it as a combat person with no political affinity at all, and I said this place is going down the drain, and it did go down the drain. I went back in '67. It took me five years to do Yankee Nomad, and I was determined that when it was published I would go to straight to Vietnam, which I did. I got a job with ABC TV and Life magazine.

AC: There are many accounts from journalists in Vietnam who wrote about a real conflict between journalists and the people who were in charge over there. Was this a problem for you?

DDD: Not at all, because I went back with the Marines. I was working with the TV station and Life with press credentials, but when I got there -- hell, I was a Marine and I'd had as much combat experience as almost anybody there. So I knew what I wanted to shoot. I shot a different kind of coverage than I did in Korea and in World War II.

AC: How was it different?

DDD: In Korea, I was tied to Marine aviation because of World War II. There's a crazy guy here in Austin named Ed Taylor. We met on Okinawa during the Okinawa campaign, and he was flying a P-38 reconnaissance fighter converted to air reconnaissance -- "flying cameras" is what they called them. He was a real wild guy. I had been trying to photograph close air support for the Marine infantry on the main battle line. I couldn't get what I wanted. We got shot up. It was too dangerous. We couldn't get close enough. I had one run where I was photographing the torpedo bombers and they shot through the glass and the guy in front of me was laid open down to his spine right between my feet. That's what kind of a place it was. I still couldn't get what I wanted. So Ed Taylor said let's fix it, and we put a plastic nose belly tank under his P-38. He was in the cockpit above me and I was hanging under his wing and he put me right down in back of these Corsairs firing rockets and dropping napalm. We went right down into the battlefront itself at about three or four hundred miles an hour. Unbelievable. No one had ever done it before.

Then Korea came and I covered it from the point of view of the dog-tired, shot-up Marine or soldier. Look, I knew how the Marines operated. I was unsure of a draftee type -- no disrespect, but one of my characteristics is anticipation: what can go wrong. What can go wrong. I knew in the Marines if I got hit, they'd drag me out, they'd patch me up and throw me out, whatever, I'd get out of there. I knew the code of combat in the Marine Corps. So I joined the Marines in Korea and stayed with them.

Then Vietnam. By this time, Indochina had been lost. Again, I assigned myself the most forward position I could find to show the life of the guys who were battered by being there. Just by being there. The cover of this Newsweek is a great example. The guy's eyes dominate the picture, and that's what I was after. The guy is not terrified. This young 19-, 20-year-old Marine is at the most forward position on the DMZ at that time. They're on a 30-day rotation and this is day 28. If he could last two more days ... He's been up all night and all day. There's mortar coming in. There's machine-gun fire coming in. We're in heavy fog. He's just worn out. This is a guy who's just worn out. That's a human being who's at the end of his resources.

|

|

DDD: That was my luck. Luck and also that's my touch. If I can take credit for it, that is my ability as a photographer.

AC: We all get in there with you.

DDD: That's trust. All the guys trusted me. Trust is everything. Nixon trusted me. When I made the shot that's in the exhibit where he's writing his acceptance speech in longhand on a yellow legal tablet, he had thrown Ehrlichman, Haldeman, everybody, out of the room and said, "Okay, come on, Dave, let's go."

AC: I also see a lot of despair and human tragedy in your photography.

DDD: But one thing, though. War is the ultimate human tragedy. You'll never find one of my photographs that violates your privacy, or if you're knocked off, your mother's privacy. I never show you any corpses or shot-up bodies. These sons of bitches today, you know, after a typhoon, after an earthquake, anything, they're right in there. That's not my privilege. I want you to feel the story of fatigue and tragedy and heartbreak. If they're dead, you'll never see their faces.