Austin Musical Theatre Hits the Heights

That's Show Biz!

Fri., Nov. 20, 1998

|

|

The group of young men dash onto the tape-lined section of linoleum that denotes the "stage" in this cafetorium serving as a theatre rehearsal space and immediately start singing and dancing their hearts out. To the insistent tunes pounded out on the nearby upright piano, they move into and out of straight lines and diagonals, arms waving, legs kicking, performing what, in the world of the musical Gypsy, passes for an old vaudeville number. And they're into it: Their fresh faces beam, full of enthusiasm, and they execute the choreography with nonchalance. They look so at ease that they might have been doing this all their young lives.

Ah, but that's to an outsider's eyes. The show's director is not quite so impressed. In fact, given the expression on his face, he might be more readily described as distressed. His mouth is drawn tight, his jaw is rigid, and his brows are lowered, shadowing his eyes, which peer at the chorus with the intensity of a laboratory laser. Suddenly, he leaves his place standing beside the rehearsal piano and crosses briskly in front of the dancers, eyeing them clinically as he moves. The glower, the clipped gate, the piercing stare, they recall a drill sergeant reviewing his platoon. Like a veteran D.I., the director is trained to take in every detail of a scene and to zero in on any part of it, however minute, that is not as it should be. Here, he scans for lines that aren't absolutely straight, arms and legs that don't move in exact syncopation; he listens for voices that have fallen off perfect pitch. And he is concerned with not only physical attributes but a sense of spirit, too: Energy must be at its peak and one's entire being must radiate nothing short of exuberance. Anything less is not good enough.

He suddenly barks out two of the dancers' names. "Smile!" he shouts to them, shifting his face to a sunny grin by way of demonstration. He doesn't stop the scene -- though if this were any rehearsal besides the first full run-through, you can bet money he would -- still, it's clear that the number falls short of his standard. He'll have to keep polishing it until he gets it to shine -- no, shine isn't intense enough for him; he'll have to keep polishing it until it will dazzle.

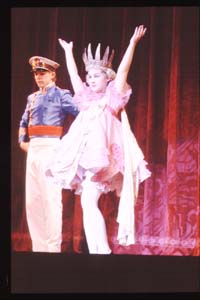

Dazzle. That pretty much sums up what this director, Scott Thompson, his partner Richard Byron, and their company Austin Musical Theatre (AMT) deliver with their productions. While the company isn't yet three years old and hasn't even a half-dozen shows to its credit, AMT's work has been so singular in character and consistent in execution that it's already firmly established its identity as an arts institution. In its work to date -- Peter Pan, West Side Story, Annie, and Gypsy, which it opened last week -- AMT has served up traditional musical fare on a scale and with a skill almost unequaled in local theatre productions. The shows that Thompson and Byron produce are big, with big casts and big sets and big songs, the kind of theatrical events that fill up a stage with bodies and light and music, and fill up an audience with warmth and dreams and romance. And these men do these old-fashioned musicals the way they were meant to be done, with that sense of the expansive, the spectacular, with so much style and spirit that it takes your breath away even as it swells your heart. They do these shows so they dazzle, as in the show-business tradition of an earlier era, as in razzle-dazzle.

And the shows are sensations. They bring thousands of people into the Paramount Theatre and inspire wild cheering from those in attendance. They're consistently lauded by critics of every stripe and honored with awards for every aspect of production.

|

|

I Know a Place Where Dreams Are Born

"Scott Thompson's here to see you." When the Chronicle receptionist buzzed me with that message back in January of 1996, my stomach sank with dread. Not dread of Scott Thompson himself -- at that time, I didn't know the man -- but dread of what I knew he wanted to talk to me about: starting a new theatre company in Austin. It is a topic I've discussed with too many people through the years, in conversations that all have a certain sameness about them. Invariably, these conversations are fueled by great idealism and a conviction that this new company will bring to Austin a kind of theatre a) the likes of which this city has never seen; and b) that will connect with modern audiences and be unusually popular. The artists sharing these dreams may or may not know how many stage companies come and go in a given season, but they always insist theirs won't make the same mistakes that other theatre companies have; theirs will be around for the long haul. Of course, they do end up making the same mistakes and they aren't around for more than a few seasons, much less the long haul. Of all the bold new groups that people have talked to me about, far more have imploded or faded away than found their audience, and knowing that has made listening to these theatrical stargazers describe their pie in the sky painful.

So here came Scott Thompson with the latest pitch. But it was apparent from the get-go that this pitch was going to be different. I could tell from the TV in his hand. Thompson was carrying a little 13-inch television with a VCR and a tape. Yes, he had a vision of a new theatre company he wanted to share with me, but he also had some evidence of his past work that would give me some visual sense of what he had in mind -- and serve as proof that he was capable of making good on it.

This was new. None of the theatrical dreamers I had encountered up to that time had given so much thought and attention to the presentation of their dream. So I watched.

And I saw this collage of musical numbers, moments snipped from various productions that Thompson had choreographed and directed through the years, a soft-shoe here, a chorus-line tap routine there, with a brassy, belted-out 11 o'clock number sandwiched in between. Even through the fuzz of video shot from the balconies of darkened theatres, the quality of the work declared itself. The steps were complex yet danced with finesse, with the performers all the while sporting that breezy air that suggests dancing requires no more effort than breathing. Clip after clip after clip, and every one had that same style: that showmanship, that sizzle, that pizazz. This was ... dare I say it? ... good. So what did this guy want in Austin?

The tape finished, and Thompson began to tell me. His dream -- actually, the dream of both him and his longtime partner Richard Byron -- was to found a new company that would bring to Austin a kind of theatre a) the likes of which this city had never before seen; and b) that would connect with audiences here and be unusually popular. At this point, my Dramatic Dream Emergency Broadcast System should have been sounding a full alert in my skull. But there had been that tape ... so I kept listening.

The company that Thompson described to me that day was as grand and ambitious and flat-out ballsy as any I'd ever heard: It would be devoted to the great works of the American musical theatre -- the "traditional Broadway musical" is the term he used -- and it would mount them on their original scale, with large choruses and multiple large sets and the like. And it would mount these productions on the Paramount Theatre stage, employing full professionals to design them and perform in them, some of them flown in from New York and Los Angeles. And its first season -- its first season, mind you -- would consist of three such productions: Peter Pan, The Music Man, and Big River.

The skeptic in me roused himself. This guy was talking about shows employing dozens of actors, at least some of them professional, in an Equity house with a thousand-plus seats ... Did he really have any idea of the scope of what he was proposing?

|

|

As a matter of fact, he did. Thompson then handed me a binder, the cover of which crowed, "Scott Thompson and Richard Byron present... Austin Musical Theatre." Inside was a mission statement, statements about the company based on questions they anticipated, bios for himself and Byron, a timeline for the company's first season, including pre-production fundraising efforts, poster art for the company's proposed first year, and -- the capper -- six detailed pages of budget figures, covering every aspect of the company's organization, from incorporation fees and office setup to postage and ad costs; all expenses for the premiere production, Peter Pan; and three separate income projections based on various percentages of ticket sales. Obviously, these were two men with considerable experience in the field who were not just talking through their top hats. They meant business. And they approached it as businessmen.

As Thompson explained, he and Byron had spent most of their careers bouncing from town to town, working on a show then moving on. Now, they were ready to stay in one place for a while, and their own production company was the key to them doing that and continuing their careers. Austin was a place they wanted to live (Byron had family already here), and they saw that the city lacked just the kind of company they wanted to start. Here was the market, with a niche they fit into like a hoofer's foot in taps.

His assessment was sound: Austin was missing the kind of company he described. That's not to say Austin didn't have any musical theatre. Hell, this was a town that had made it a matter of civic pride to go sweat out the hottest nights of the year on a crowded hillside just to see a musical. This was a town that had made a revue of Sixties pop singles into a theatrical phenomenon outstripping even A Christmas Carol. Austin adores musicals, and dozens of the city's theatre companies had been serving up song-and-dance for decades. There was musical theatre, all right.

But not the kind that Thompson and Byron were talking about. They meant musical theatre the old way, the old Broadway way. They were talking about the works that defined the form in all their grandeur and ornamentation and by-god-watch-this show-stopping pleasure. They meant a kind of theatre that wasn't being created anymore -- at least, not in the way it once was -- but a kind that, if you treated it with the care and fullness that its original productions were given, could still thrill audiences of all ages. If their theatrical specialty were anything other than mass appeal spectaculars, pop culture entertainments, Thompson and Byron would probably be considered period artists, staging works in the style and sensibility of their original productions. But musicals have yet to acquire the cultural respect accorded Elizabethan drama or Shavian comedy, so Thompson and Byron were left to peddle their dream with little but their own belief that it made sense and that it belonged here, and their drive to see it through.

There was a lot of drive there. Thompson lugged that TV all over the city that January and for the next couple of months. He estimates giving more than 100 presentations, averaging three a day for 10 weeks straight. If he heard about someone who was willing to listen, he'd go make the pitch: corporate group, nonprofit board, sewing circle ... Thompson was there. He was the trouper of the old show-biz cliché: knowing his routine, playing the house, giving his all no matter what day of the week or how small the crowd.

Now, imagine another show-biz cliché, this one from the movies: the calendar on the wall from which page after page flies away to convey a sense of time passing. A year has passed since Thompson's visit to the Chronicle. In the intervening months, Thompson and Byron have won their first big show of public support through Austin Musical Theatre's first gala fundraiser, featuring Broadway star Patti Lupone performing her solo concert show at the Paramount; they've attracted a big-deal producer, Charles Duggan of the Greater Tuna theatrical corporation and gravy train (who informed Thompson of the arrangement in a casual aside at the B. Iden Payne Awards, seconds before announcing it publicly); scheduled a one-week run of Peter Pan; lured two New York performers, Broadway vets Kristi Lynes and Jonathan Freeman, down to Austin to play Peter and Captain Hook, respectively; cast the rest of the company locally, including a passel of teens and pre-teens; and rehearsed them like most of them have never been rehearsed before. Now, it's down to the wire, the final days before the big debut, that period when every moment is caught up in either the manic giggles of anticipation or the clammy flop sweats of terror, and suddenly ... everything ... freezes. Literally.

|

|

Thompson and Byron have the grave misfortune of slogging their way through tech week -- a week that can be unmitigated hell under the best of circumstances, but which is complicated here by the fact that Thompson and Byron are working in a theatre they have never worked in before, with technical support personnel they have never worked with before -- during the city's worst ice storm in years. Streets are completely frozen. People are sternly discouraged from driving by every cop, highway patrolman, and weathercaster within the city limits. The city shuts down. Thompson and Byron have no choice but to cancel not one dress rehearsal but two. And during the days when the production is stalled, sales stall, too. The situation is bleak. But then, as if on cue, as if dictated by a hoary old script for some sappy old musical, the sun comes out. The city thaws. The phones begin to ring. Tickets sell like ... well, what else do tickets sell like but hotcakes? The show opens. Crowds leap to their feet. The response is so enthusiastic that the money men -- played here by Duggan and Paramount general manager Paul Beutel -- huddle with Thompson to discuss ... extending. The first show, with everything -- even Mother Nature -- thrown at it to keep it from succeeding, and nothing stops it. It's a smash, such a smash that it's held over. If you saw it on a stage, you wouldn't buy it. Or maybe you would -- which is just what Thompson and Byron are banking on.

Catch the Moon/One-Handed Catch

As tantalizing as the show-behind-the-show turned out to be, AMT's Peter Pan was more than a show-biz fable come to life. It was validation that Thompson and Byron knew what they were doing and that their vision, grand and ballsy as it may have been, was one they could realize. It also set a high bar for the company to match. The quality of the performances and the dancing in particular were unusually impressive, especially for a town in which hoofers of distinction are about as rare as humble directors. AMT would have to work as hard or harder to assure Austin that it could work its magic on an ongoing basis.

As it turned out, Thompson and Byron won an opportunity to prove themselves again without having to mount another AMT production. That spring, they were hired to stage Grease for the Mary Moody Northen Theatre at St. Edward's University. They didn't have the luxury of casting outside Austin, but that didn't stop this team from inspiring its student cast to new heights of performance. The energy and discipline evident in that production exceeded almost any I've experienced at that school. And, as with Pan, the show was a box office sensation. The public streamed in, and when the run was over, the theatre scheduled a follow-up run in June.

Following Grease, the big question about AMT -- "Can they do it again?" -- pretty much faded away. In its place rose up a sense of anticipation for the next project, the next bit of razzle-dazzle. Anyone hoping it would be one of the two other musicals that Thompson and Byron had selected for their debut season would be disappointed. The two decided that The Music Man -- while a favorite of Scott's -- wasn't a realistic choice for AMT at that point in time, and while they felt that Big River would work as part of a full season, it didn't seem to stand on its own. So they searched for another musical that was well-known and had a broad appeal and was different enough from Peter Pan to expand their audience and the public perception of what AMT could do. They chose West Side Story.

As musicals go, it's certainly popular and it's 180 degrees from Pan in mood and sensibility. But it's also an enormous challenge, with much greater dramatic demands than most musicals, bold, complex music from Leonard Bernstein, and, if you opt to follow Jerome Robbins' original choreography, a lot of athletic dancing. None of that deterred Thompson and Byron. They found their company and put together as big and daring a production as they could.

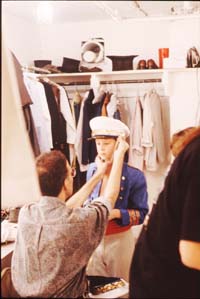

I was fortunate enough to be part of the company for that production and so was able to observe their work from the inside. Much of what I saw was craftsmanship, a steady, insistent pursuit of excellence. Rehearsals were tightly scheduled; scenes were drilled and drilled and drilled. Getting to a level of proficiency was key; you had to reach that point where you can execute the moves without thinking about them. Then, you could focus on the feeling, being in the scene, making whatever you were doing look natural and effortless. Oh, there was temperament, as there is in every theatre project. There were demands, there was shouting, but less than you might think. Mostly, there was work, the relentless push, push, push toward perfection.

AMT's West Side Story may not have reached that point of perfection, but it went after it with all the urgency and vigor of a high school athlete racing for the end zone. The show's striking look -- the outstanding work of Christopher McCollum -- and energetic dances gave Austin audiences something truly dynamic. And the craft of the piece was so strong as to confirm in all but the most resistent camps that AMT was the real deal.

With West Side Story, AMT made good on the Austin in its name; it was truly part of the city now. That was evident in the way people came to the show, talked about it, criticized it. There was acceptance there. Perhaps the strongest measure of the company's place in the community came through some parody numbers aimed at AMT by Naughty Austin, a local cabaret company in the vein of Forbidden Broadway. It isn't every theatre group that in its first year is already enough of a fixture on the scene to warrant being satirized.

The Pulse, the Beat, the Drive

|

|

The follow-up to West Side Story was a shift back to the family-friendly musical. Thompson and Byron were savvy enough to know that at least part of their bread would be buttered by teaching young would-be Bernadette Peterses and Tommy Tunes how to sell that solo and then shuffle off to Buffalo. Early on, they established an AMT school for kids wanting to learn singing and dancing, with the added appeal of it being the first step toward getting cast in one of the company's shows. Pan had had all those lost boys and Indians, and Thompson and Byron had filled the parts with local kids. West Side was not a kids' show, so the third production would be. Thompson and Byron's choice: Annie.

You could almost hear a collective groan from the local theatre community when the decision was made. Not Annie. To most actors, it's a maple syrup show -- pure sap -- painful to watch, painful to perform, and, as if that weren't bad enough, it has the two things you never want to share a stage with: kids and a dog. Of course, most of these folks could forgive AMT for doing Annie. They understood that it would bring in the families, which would bring in the green, which would make the company's financial position even more secure, and that was good. They just didn't think the show would be. Good, that is.

In a way, it didn't need to be. Expectations are high for the first show, and everyone is watching the second show for that sophomore slump. You ace those two, and people won't look as closely at the third. They'll give it to you. This was the one where they could coast. But they didn't.

AMT's Annie opened, and it was like a spring breeze blowing in from the south on a March day. It was fun, it had heart, and it was as imaginative and sharp and full of spectacle as either of the company's first two shows. It didn't look down at the material; it treated it as fresh.

And so it was. A song as stale as "Tomorrow," that anthem to optimism that has become synonomous with saccharine and is treated with contempt by anyone over the age of 13, came across as fresh. Though you knew it was coming -- it's Annie, how could you not know it's coming? -- when it arrived it seemed not some calculated showstopper, some drippy, schmaltzy Broadway number, but a song born of the moment, from a dramatic character named Annie, a plucky kid who was determined to hang onto hope, no matter what. When you think of it that way, it makes sense, but most of us haven't thought of it like that. It took a company -- a company that has a lot in common with a certain red-headed orphan -- to show us.

Nothing's Gonna Stop Us Till We're Through

So now, it's November and AMT is working on its fourth show, Gypsy. And while every show that this company has done to date has revealed something about it and the men who founded it, this is the one that will tell you the most about why Scott Thompson and Richard Byron are in the business they're in and why they have come to Austin, Texas, and tried to start this enormous enterprise of staging musicals in an old vaudeville house. It's show biz. Call it another cliché of the stage, but it's in the blood of some people. They have to sing, they have to dance. And if they can't do it themselves, they make it so other people can. It's just what they do. The light out on the stage is magic.

Gypsy is a story about such people, from the idealistic young dancers to the haggard old strippers to the stage mothers who push, push, push their kids to that point of perfection. It's about people who live in that life of the stage, that dream life, however they can, however poorly. I look at the room in which AMT is rehearsing, and it seems so ill-suited to shaping that magic of a performance: Powder-blue walls and scarred beige linoleum and fluorescents raining hard light on everything. And yet as the rehearsal proceeds, despite this place, despite the street clothes on the performers, the story pulls me in. I watch, and I am moved by the struggles of these girls on a stage and their relentless dreamer of a mother. And I understand how material like this -- the great musicals of Broadway -- has been able to enchant thousands upon thousands of American kids whose only exposure to them has been in the humble circumstances of community theatre productions. These are great stories, and the form in which they are created is a great form. Give it just a little, and it moves us.

So people are captivated by it, and they give over their lives to it, facing whatever comes, never stopping until they're through. Austin Musical Theatre is a company founded by those people. Looking at Thompson and Byron during the rehearsal, they are almost perfect opposites: Thompson standing, intense, voice pitched high, gulping in all the activity and frantically scribbling notes on a legal pad with his red pen; Byron squatting peacefully, face relaxed, soaking it all in, voice soft and low, never making a note. But you see in their eyes, in the way they watch, that show-biz passion.

There's really nothing else that's needed to prove that these men are the characters in Gypsy, that what they're giving us in Austin Musical Theatre is the exquisite dream and drive of show biz, but then life comes along and gives it to you anyway, in the most sublime way. Onstage, the scene is an audition, with Dainty June singing and her mama, Rose, off in the stage right wings. In the scene, Mama Rose is staring at her girl, mentally willing her to do well, and the actress playing her here, Pamela Myers, is leaning forward and mouthing the words that June is singing. I take my eyes off the scene long enough to look at Scott Thompson, and he is standing on the opposite side of the stage beside the rehearsal piano, and he is leaning forward and mouthing the words that June is singing.

And that, as they say, is show biz.