On the Edges of Gentrification, Planning a Different East Riverside Drive

City's declared goals for the corridor and those of private developers do not necessarily coincide

By Michael King, Fri., Feb. 15, 2019

For most Austinites, East Riverside Drive – from I-35 to Texas 71 – is primarily a road from somewhere to somewhere else, a six-lane boulevard flanked by strip malls, fast food joints, and enormous parking lots. Hit it at the wrong time, and you'll find yourself working slowly from stoplight to stoplight. At less gridlocked hours, you'll hope to match the highway speeds sufficiently to discourage lane-jumpers zipping around you. At large scale, it's an asphalt anachronism: an inner-city expressway surrounded by intense, sprawling, but aging development, a low-rise market district readily accessible only by car.

"What to do about Riverside?" has been a question confronting nearby residents as well as city planners for years, one that has spawned public outreach, master plans, mobility plans, planned unit developments, and regulating ordinances all aimed at redeveloping the corridor to be less of a highway from Downtown to Austin-Bergstrom International Airport, and more of a welcoming destination.

As with the other "corridors" central to the city's linked transportation and housing goals, the Riverside plans express broad goals of greater housing density, less domination by automobiles, more human scale – in sum, a more residential-and-multimodal cityscape. The 2010 East Riverside Corridor Master Plan contemplates a range of interrelated goals: upgraded "green" infrastructure, more open space and connectivity, better mobility (including rail or bus rapid transit), transit-supportive residential density, better cityscape design, and more affordable housing (preserved and new). Meanwhile, Austin's burgeoning real estate market has laid out its own path – bringing major apartment, retail, and hotel construction along Riverside from end to end. Major projects have included AMLI South Shore on the west, the Oracle campus and South Shore District along Lakeshore Boulevard, and most recently, major proposed projects just east of Pleasant Valley.

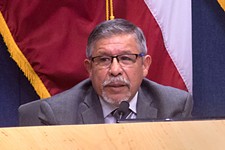

Although much of their public rhetoric can sound similar, the city's declared goals and those of the private development projects do not necessarily coincide. Council Member Pio Renteria, whose District 3 is centered on the Riverside area, describes the ideal outcome for the corridor as akin to that of the still-in-progress Mueller neighborhood. "I see it, hopefully, as becoming one of our hubs," he told me, "where people can live there, walk there, have their entertainment there, work there. It could become like Mueller – and give us 25% affordable housing, because we all could enjoy that. You want people to be able to live there who are not necessarily high-income."

Private developers don't necessarily disagree with the Council member's long-term goals – and especially in public, they'll be happy to endorse them – but on the ground they generally have more specialized short-term goals, led by maximum financial return for their investors. The challenge for city planners is to find ways to encourage quality development that doesn't entirely sacrifice community benefits like housing affordability and density for private profit. The Riverside area looks likely to become a test case for that ongoing attempt at balance.

It's worth remembering that the Mueller development, built on Austin's prior airport, was entirely city-owned land. That meant elected officials and city planners could set the terms of the eventual development plan, including its requirement that 25% of all residential units be affordable. Even with that benchmark, as housing prices at Mueller and in Austin continue to soar, affordability has been difficult to maintain – prompting the Travis Central Appraisal District and the Mueller Foundation (which administers the affordability program) to wrangle periodically over how to account for appraised market value when affordable properties change hands.

Big Plans, Big Developments

Consider this (partial) list of attempts in contemporary times, by city officials, planners, developers, and participating residents, to wrap their collective arms around the future of East Riverside:

2006, November: East Riverside Combined Neighborhood Plan

2007, May: Lakeshore Planned Unit Development (50.1 acres below Lakeshore Boulevard east of Pleasant Valley)

2009, December: South Shore District PUD (20.17 acres near Riverside & Lakeshore)

2010, February: East Riverside Master Plan

2013, May: East Riverside Regulating Plan

That is, the city approved major PUDs to redevelop Riverside in 2007 and 2009, and then an aspirational master plan, and then, finally, in 2013 an enforceable set of regulations to promote the vision for the corridor. The horses hadn't entirely left the barn, but the city was rounding up livestock on the run.

Meanwhile, additional projects have been announced or are in progress to join the Lakeshore and South Shore District PUDs. The Towers.net online site, which tracks real estate news, recently summarized (in part) the current plans in the area of just one firm, the Presidium Group: "The company's portfolio includes the roughly six-acre shopping center at 2015 East Riverside Drive, the Element Apartments at 1500 Royal Crest Drive, the Solaris Apartments at 1601 Royal Crest Drive, and the recently-completed Edison Apartments at 4711 East Riverside Drive – and that's just the beginning. The crown jewel of the firm's holdings in this area is the 97-acre assembly comprised of five tracts clustered around Wickersham Lane near East Riverside Drive, only one block east of Pleasant Valley Road." The latter is currently the site of the Ballpark Apartments, where some residents have loudly objected to Presidium's grand plans, which are expected to reach City Hall for official review sometime later this year.

Less visible to the traffic flying by on the corridor, the East Riverside neighborhood planning area is bounded by Lady Bird Lake on the north, I-35 on the west, South Pleasant Valley on the east, and East Oltorf on the south. East Riverside Drive bifurcates that neighborhood from northwest to southeast, segregating the tonier, lakeside section from the older, mostly working-class areas to the south and east. (Farther along to the east is Montopolis, not yet a nexus of the same level of development intensity, but likely to feel its effects in due course.) The physical divider of the commercial "corridor" properties straddling the roadway has, in recent years, increasingly become an economic divider, as development projects designed primarily to accommodate well-paid professionals have begun to accumulate between East Riverside and the lake.

The streets south of East Riverside are also lined with apartment units, but older and cheaper than those to the north. These buildings date to the Seventies and Eighties, and once housed mostly college students, a cohort that's now moved back to West Campus as that neighborhood has densified. In their place have followed waves of working-class, mostly Latino renters – with, as is often the case with Austin rental housing, a high rate of resident turnover. The 78741 ZIP code, which includes the Riverside neighborhood, is about 55% Latino, with that community being concentrated to the south of the corridor.

The redevelopment pressure accumulating along the corridor, in the projects built or in progress from I-35 to Pleasant Valley, hasn't yet made much impact to the south – a couple of new developments have broken ground on vacant land, but as yet few of the older apartments have been marked for replacement or upgrade. Nevertheless, many are near the end of their predictable life span, and quite a few are in deteriorating shape – collecting code violations that mandate often expensive repairs. Renteria cited a 2017 city agreement to waive fines against a complex just south of the corridor, in return for the new owners' commitment of millions in renovations aimed at achieving compliance. But officials have traditionally treaded lightly to avoid tipping the scales and making these properties ripe for teardowns.

The East Riverside corridor is almost entirely privately owned land. That means, Renteria acknowledges, there are relatively few official tools to enforce affordability, primarily the city's "density bonus" program (which allows additional zoning entitlements, like height, in return for community benefits like more affordable units). Few developers have thus far taken advantage of density bonuses in the corridor (some are reportedly in the pipeline), and in any case, says Renteria, state law restricts such programs to requiring no more than 10% affordable units. Developers occasionally agree to a greater level of affordability – usually with a city "buy-down" of some units. Should the current market pressure extend beyond the corridor into the more affordable streets to the south, there's little the city can do to stop rising rents and ultimately gentrification as affordable properties with working-class tenants are replaced by higher-earning professionals, families replaced by younger singles.

"That's my biggest fear, that we'll eventually end up losing all these existing apartments," said Renteria, anticipating moderately upgraded units to be rented for top dollar. "They'll put a few bucks in there, make it look real nice, and convert it into high-end units." City Council members say that where the density bonuses apply, they're hoping to obtain in exchange more affordability, especially for current or former residents. "What we want to see is the right to return, and the right to stay," Renteria says, "and that's what we're going to be requesting for additional entitlements [e.g., greater height]." But if developers decide that they'll enjoy more flexibility under existing entitlements, outside the bonus program, there's little the city can do to persuade them otherwise.

City planner Anne Milne, who focuses primarily on the corridor itself, says it's inevitable that private landowners will want to redevelop and upgrade older properties, and that within that market context, the city's role is primarily to encourage better quality development (the multimodal context, mixed-use, open and connected design contemplated in the Master Plan). "Austin as a whole – we have a huge demand for housing," Milne told me, "so that even places built 30 to 40 years ago are getting top dollar. Older housing in the Riverside area often exhibits a lot of code violations, and the answer to affordable housing is not to have terrible housing." Ultimately, Milne says, the Riverside area needs more housing units of all types and prices, in a built landscape that de-emphasizes large blocks dominated by parking lots. "We cannot solve the housing crisis by not building."

Milne is aware of the pressures of rising prices – rising rent motivated one of her own Austin relocations – but argues the city's obvious need mandates more housing. "We need more housing everywhere across the city. ... The more we stop that, the more we're pushing people out of the central city." Asked what she thinks of the ongoing public discourse over whether housing density is a sufficient affordability tool, she adds nuance. "Density does not necessarily equal affordability, but you can't get affordability without dense development. We need more units. A lot of them are going to be new, luxury housing units, because that's what the market is demanding right now. Those people need to live somewhere, and creating more dense development here [near Riverside] will take some pressure off the market in other places. It [density] doesn't solve the problem, but it's part of solving the problem."

The Human Scale

Closer to the ground, among current Riverside area residents, the broader policy arguments can seem abstract. Larry Sunderland, a homeowner who's lived in the Riverside neighborhood for decades, recently gave me a busman's tour from Lakeshore Boulevard to Oltorf, while describing the changes he's seen during that time. The big ones are obvious – huge apartment complexes just east of I-35 along Riverside, the Oracle complex still emerging along Lakeshore Boulevard, similar projects in the works along Pleasant Valley. He also notes anomalies: still-empty storefronts on the ground floor of those high-end apartments, despite thriving restaurants and other shops in the same blocks. "Maybe the residential density hasn't justified the business rents yet," he says. Farther south, among the rows of older apartment complexes north of Oltorf, there are a couple of projects beginning on open land, but Sunderland says he hasn't yet seen signs of broad redevelopment of those older complexes. Older homeowners like himself are somewhat insulated from rising prices by property tax exemptions for seniors.

Sunderland works with the Episcopal Church of the Good Shepherd on the Hill, on its community garden and children's programs. He also helped organize a new neighborhood association (Friends of Riverside ATX), although he admits it's slow going. "It's difficult to get more than a few people to attend meetings or get involved." There are few adequate community gathering spots – Good Shepherd is one, Parker Lane United Methodist Church is another – and residential turnover in the apartments makes continuity more difficult.

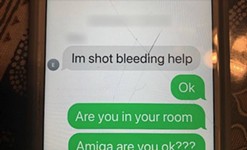

Sunderland occasionally has found himself on the front line of the arguments over gentrification. During a November arts festival to mark the initiation of an eventual Arts District to be anchored on Pleasant Valley – sponsored by the Austin Creative Alliance and underwritten in part by Presidium – Sunderland was allegedly assaulted by some protesters demanding a boycott, led by the would-be revolutionaries who call themselves "Defend Our Hoodz." (Two accused attackers were arrested, and their cases are pending.) Online, DOH celebrated the assault, blaming the 67-year-old Sunderland (see "Defend Our Hoodz," Feb. 15).

The Austin arts community has been divided over the call for a boycott. While many artists and arts groups have welcomed the proposed Arts District as promising new places to work and cheaper rents, a few have said they can't support a project underwritten by a major developer. John Riedie, director of the Creative Alliance, says a couple of board members stepped down over the issue. He understands their objections – "everybody's got to make their own choices" – but says his dealings with Presidium have been positive and encouraging, and that arts organizations, artists, and other Riverside residents need both public and private support to survive the inevitable changes along the corridor.

Riedie said he objects to the reflexive use of "development" or "gentrification" as "trigger words" to stop all conversation, and that much of the proposed redevelopment along the corridor and specifically near Riverside and Pleasant Valley is overdue and necessary. "If buildings are worn down beyond their useful age, redevelopment is not 'gentrification,'" he said. More housing is desperately needed, he argued, as well as working space for nonprofit groups, and that current redevelopment plans for the neighborhood would potentially "triple the housing capacity."

One current Alliance project is a gallery show by artist Jean-Pierre Verdijo, which he calls "Agency at the Crossroads" (opened Feb. 7) – not by coincidence, a meditation on urban change, gentrification, and its broader implications. On a gallery wall at the Alliance office on San Marcos Street, Verdijo (who works in a wide range of media) has painted a brief commentary on the meaning and effects of gentrification – comments partially obscured by slats representing a white picket fence. Verdijo says he feels torn by the calls for artists to boycott the Arts District project, when it represents an attempt to create physical spaces for artists to survive. "My show is in part about how artists themselves are charged with the gentrification process, when the protesters don't stop at the construction site and tell the workers – oftentimes Mexican laborers – not to build the building. ... Artists are the only group that this happens to ... artists trying to get by, to make a living sleeping in their studios with a hot plate. What I'd like to see is unity."

Verdijo argues that the Austin housing crisis, affecting everyone of low or moderate means, is inevitably part of a much larger, common predicament. "Gentrification is really a fruit of a much greater issue, which is income inequality. I don't think anyone doesn't want redevelopment of poor areas. But the people who live there now need to be able to afford those new services."

It remains to be seen whether along Riverside and elsewhere, Austin – public and private interests together – can succeed where so many other cities have failed: to accommodate rapid growth, including rapid expansion of housing and services, and yet somehow provide affordability and equity for the people already here.

Reconfiguring Riverside

Despite its name, the East Riverside Corridor heads southeast and away from the river (Lady Bird Lake) to Texas 71 (East Ben White) near the airport. The Corridor Regulating Plan, which includes detailed prescriptions to promote walkable, mixed-use, transit-supportive development, encompasses the properties where change is more likely in the near- to mid-term. Among those are the multiple sites now owned by Presidium Holdings, whose plans for a "new Domain" to replace what are now working-class apartments have fueled concerns about affordability and protests against gentrification. Closer to I-35, the Riverside neighborhood (as defined in the East Riverside/Oltorf Combined Neighborhood Plan adopted back in 2006) is home to the Lakeshore and South Shore District PUDs and the growing Oracle campus, but also contains working-class housing that is nearing the end of its life span; those properties, south of the corridor and outside the Regulating Plan, have seen less interest from developers – as of yet.

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.