Hancock Center, R.I.P.

Everything Old Is New Again at 41st & I-35

By Mike Clark-Madison, Fri., Feb. 14, 1997

photograph by John Anderson |

It's plain fact that the new Hancock Center, as described by its developer to the Chronicle, the local neighborhoods, and others, doesn't wear well the labels that, elsewhere in this issue, we see hung on central-city redevelopment. Innovative? Revitalizing? A step toward sustainability? Highest and best use? Compatible with its surroundings? Pedestrian- and transit-friendly? Mixed-use? A community crossroads? If all this New Urbanist compact-city traditional-development rhetoric gives you hives, the new Hancock Center promises to soothe your painful rash better than Gold Bond.

Is this a drag? Sure. Could it be otherwise? Probably not, at least not yet. It's one thing when you're dealing with local owners and developers who know their city and their market, or with "alternative" financing sources for whom "return on investment" may mean something different than it does to your average bank. And in Austin, you'd be hard-pressed to find an architect who wouldn't itch to convert a 34-acre site, squat in the city center, bridging a preserved heritage neighborhood and a high-impact commercial corridor, into an award-winning progressive planning hallmark. It's different if you're Pacific Retail Trust, the out-of-town REIT (real estate investment trust) that ended up with Hancock after the usual passel of post-bust portfolio swaps. All they have is a formerly hot property that's lapsed into dereliction, without either an instrument or an incentive -- like, say, a city-wide comprehensive plan, or building and zoning regs that promote infill development, or even (egads!) design guidelines -- to make it into anything but a sure-thing lowest-denominator project. Who can blame them?

So Lincoln Property Corp., the Dallas-based manager of the Hancock project, is moving forward into, if not the distant past, at least the middle of last week, without (at least to this point) more than a low-frequency grumble from its neighbors. And central-city partisans can call Hancock the one that got away, consoled by the notion that anything is better than the nothing that Hancock had become. But before we forget about Hancock Center, we should remember how Austin's first shopping mall got there in the first place. The once-beautiful, later-homely and now-dead pile of brick occupies a niche in River City history, not just as a landmark of commerce, or even of Central Austin, but as the arguable progenitor of every neighborhood-vs.-developer contest that's left blood in our leafy streets. The story of Hancock's creation shows us how little difference 40 years makes -- perhaps the death of the center has spawned so little noise because its birth spawned so much.

Royally Consummated

Back in 1946, what is now Hancock Center was part of the grounds of the old

Austin Country Club, a 92-acre tract owned and developed by former Austin mayor

Louis Hancock, perhaps the very first of the River City's subsequent legions of

golf nuts. The City of Austin paid $175,000 for the whole property, which it

subsequently rechristened the Hancock Golf Course, even though the actual links

only occupied some 58 acres. The remainder, known inevitably as the Back Forty

though it was in actuality only 34.2 acres, was naught but a sandlot, and when

the City Council finally got around to dedicating the Hancock property as

parkland, in 1951, it specifically excluded the Back Forty from that

designation. To not do so would have required, then as now, that the public

vote on any proposed sale of the property.Nearly a decade later, in December 1959, the districts around Hancock Golf Course had seen limited residential growth (mostly in multi-family complexes such as pockmark Hyde Park today) and substantial commercial growth along the old Interregional Highway, including Delwood Center (sometimes claimed as Austin's first shopping center, as opposed to a "mall") across then-US87 from what had by then been dubbed the East Forty. During the 1950s, the city had turned down two offers for this surplus land, including a $375,000 bid from Safeway, but in October 1959 it was approached by Sears, Roebuck & Co. through its Homart development subsidiary. The locals, having become accustomed to both a large vacant tract in their midst and a lack of city desire to do anything with it, were both stunned and offended when the Planning Commission rezoned the property for high-powered commerce, without disclosing that this change had been requested by Sears. Come December 8, the East Forty was auctioned, with Sears as the only bidder, and as the Austin American reported, "The sale was consummated in less than two hours." In the view of many citizens, "consummated" was an aptly metaphoric euphemism for what actually transpired.

The 28-store, $9 million "mall" proposed by Sears, while becoming a fixture in the sprawling suburbs of the big cities, was still a fairly novel concept in smaller, more compact towns like Austin, where most people still did most of their shopping downtown on Congress Avenue. To many local eyes, the Sears project was a behemoth, inappropriate for Austin and designed to meet commercial needs that didn't exist. Opponents ranged from local retailers, to neighbors who considered the East Forty an undeveloped park and theirs a purely residential neighborhood, to golfers who foresaw the degradation and destruction of the Hancock course, to forward-thinking planners (professional and armchair) who envisioned higher and better uses of the tract, to taxpayers'-rights advocates (then often known by the simpler label of "cranks") who felt the city was getting, well, consummated by Sears and its high-priced, big-city lawyers.

So off to court they went. On the day before the city's December tryst with Sears, a sortie of citizens filed both a petition with the city clerk and a lawsuit with the district court, both calling for a public referendum on the sale. The city laughed heartily, disqualified the petition in record time, pointed to its 1951 vote to exempt the East Forty from parkland protection, and proceeded to spend Sears' money hither and yon -- but never asked Judge Herman Jones to dismiss the suit. While that dormant legal action cluttered up the judge's desk for three years, Sears could not obtain financing, sign contracts, or break ground.

Goliath Won

In 1962, an impatient Judge Jones reversed the sale of the East 40 and ordered

a public vote, declaring that the tract was indeed parkland, since it had been

used as a park both when the city bought it and since. The ensuing election

battle, in reflection, should belie any notion that -- as we moderns are often

told by our traditional elite interests -- Austin used to be a happier place,

where issues of public import were resolved by polite gentlemen and ladies in

an atmosphere of consensus. If anything, Austin today is more civil than it was

in early 1962, if only because our activism and vitriol is today reserved, at

least at the citywide level, for matters larger than a 34-acre tract of land.

Even in present-value dollars, $800,000 and a parcel the size of Hancock Center

do not today add up to an incendiary political issue.But back in 1962, this called for breaking out the War-Declared type and full-page-ad political hype. "Your council has acted in the public interest," said the Vote-Fors, organized as the "Hancock Election Committee," pointing to the usual fruits of progress. More jobs, both in construction today and in retail tomorrow. More tax revenue, and money for improvements to parks all over the city. (That's where most of Sears' $800,000 had been spent three years earlier.) The city already has 50 acres of parkland in the area, they argued -- how much more do you need? And other points that could have been written by Ronney Reynolds, including the wonderful clincher, "We should support the judgment of the men we elected as our city council!"

|

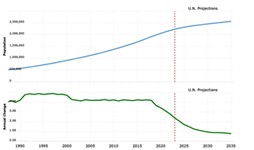

Hancock Center is being partially demolished to make way for a new HEB Superstore and other retail space. The Hancock Center of 1998 stands in stark contrast to the original site plan from 1971. |

We wouldn't be talking about this if the alarums of the Vote-Againsts had not failed, albeit narrowly, to persuade the electorate. And certainly in hindsight we know that the worst of their fears were not realized, no matter how bad traffic gets at 38th & Red River. By May 1964 Sears' grand creation opened its doors, hailed by the press, the business community, and the city government as a wonder of the modern world. Even without the heavy leavening of boosterism, Hancock Center turned out to be pleasantly surprising to its detractors. To tastes of the time, it was mighty attractive, with its "parklike" setting, famous fountains, tinkling background music. Its subterranean Town Hall promised to be a crossroads and gathering place for the same citizens and neighbors who had expected the center to turn its back on its surroundings. And Austin, used to development that was even more ad hoc and nearsighted than what we see now, had never seen anything so big -- at 500,000 square feet, Hancock was possibly the largest purely private-sector project in Austin at that time -- that had been master-planned as a whole and built out to its full future size by Opening Day.

Pulling the Plug

It seems unlikely that the creators of Hancock Center thought their "oasis of

grandeur," their "unsurpassed pleasure" in "a setting to dazzle the

imagination," would exhaust its design life in less than 30 years. Or perhaps

even more quickly than that -- as late as the 1980s, most of Hancock was still

occupied (although one of the original buildings had already been razed), all

the anchor department stores were in place, the HEB was just a grocery store

rather than a mega-market-extravaganza, and the fountain still worked. It

wasn't until the current decade -- when many of the trends we presume killed

off Hancock Center, like megamall competition, the flight to the suburbs, and

The Bust, had already begun to diminish in their impact -- that Hancock slipped

from an underperforming retail complex to a terminal case. This would imply that large-scale development projects are really a lagging indicator of trends on the ground in Austin, which should come as no surprise to anyone who wonders why, for example, we're still fighting about unbuilt subdivisions in the Barton Creek Watershed that fewer people by the day consider convenient or attractive or worth their retail price. And ironically, even if we concede that a dramatic transformation of the old East Forty into a New Urbanist showpiece was never likely, a lot of the things we now look for in developments, and can't find very readily in what we've seen of the new Hancock Center, were part of the old Hancock Center from the beginning: a self-contained, master-planned project, complete with public spaces, multiple uses, and native plants. Ditch the massive uninterrupted parking lot and add some small-scale buildings around the property's interior edges (on Red River & 41st Street), and Hancock Center would have been a quite decent hub for an urban village.

But such is not to be. Instead of a physical legacy, we are left with a set of lessons. Like how nothing ever changes, how the way we used to build things is the way we should build them, how neighborhoods have always fought for what they see as their integrity, how power interests have always fought the neighborhoods, how the most heated and bitter conflicts are repeated endlessly, as if they were being slugged-out for the very first time, even as the wounds and scars of last year's battles not only heal but disappear. Everything old is new again -- a fitting sentiment for a eulogy, don't you think? Hancock Center, may you rest in peace.

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.