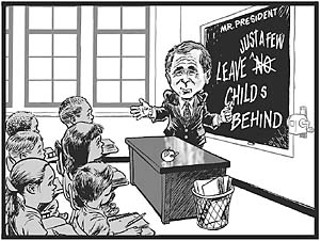

Leave No Child Behind

Education policy in George Bush's America

By Louis Dubose and Molly Ivins, Fri., Oct. 3, 2003

You teach a child to read and he or her will be able to pass a literacy test.

-- George W. Bush, Tennessee, Feb. 21, 2001

Where did this idea come from -- that everybody deserves free education? ... It's like free groceries. It comes from Moscow. From Russia. Straight out of the pit of hell.

-- Representative Debbie Riddle, Austin, March 5, 2003

OK, so we're not real partial to public education in Texas.

And we got fooled. Maybe more than twice.

So did you.

Here's how it happened.

Between GeeDubya Bush's second legislative session in 1997 and the official beginning of his run for the presidency in 1999, the state of Texas pissed away much of a $6 billion surplus. A surplus in Austin is like the hundred-year flood in Amarillo: it comes about every eight hundred years. You want to make full use of everything you can get out of it.

Governor Bush made good use of the surplus, at least for his own political purposes. In a state known for low taxes and no income tax, he gave a big chunk of the surplus back to taxpayers. Then he ran for president saying, "I passed the largest tax break in the history of the state of Texas." And why not? The economy was booming. Enron stock was going to hit $100 and split. Streets were filled with trucks laying fiber-optic cable. If you could get a table near the lean and hungry venture capitalists at the Mezzaluna restaurant in downtown Austin, you might hear one of them mention "the next killer app." Then you could call your broker, sell Agillion, and buy Tivoli. The boom was like Robert Earl Keen's song "The Road Goes on Forever and the Party Never Ends."

Dubya Bush arrived as governor after the party started. By the time it ended, he had ridden the Texas tech boom all the way to the White House. The first big Austin campaign bash in the summer of 1999 featured bad country music and a stump speech heavy on Bushonomic blather: "... the largest tax cut in the history of the state of Texas ... give tax dollars to the people who earned them ... ," etc. Bush budget director Albert Hawkins, who had just left the state's payroll to join the campaign, stood at the back of the crowd. Hawkins is a veteran capitol numbers-cruncher who knew better. Asked why none of the record surplus was banked in the state's rainy day fund, Hawkins dismissed the question. The state's finances were in good shape, he said. "We didn't see any need to put any money in the fund."

Then the stock market tanked, the Supreme Court named Bush president, tax revenues disappeared, and Texas went broke. As we write, we're looking at a $10 billion deficit in Texas ... It's raining in Texas. Six or seven billion dollars in the Texas rainy day fund would be right useful to legislators slashing programs in a state that's always in a dead heat with Mississippi for last place in government spending. As Bush rolled out his second big tax cut in Washington in 2002, the state he left behind was being ravaged by the deficits he created.

One casualty of the post-Bush budget crash in Texas is the state's public schools. That's how Odell Edwards -- along with all but 8% of his African-American classmates at Houston's Phillis Wheatley High School -- really got fooled. As Odell started tenth grade, his school district faced a $160 million deficit. His campus was rated as "low-performing." And there was a 92% chance that in two years he would fail the "high-stakes" test required by President Bush's "No Child Left Behind" education-reform law.

Odell gets Bushwhacked twice.

Governor Bush's tax cuts in Texas put Odell's school district in a financial bind. President Bush's No Child Left Behind law puts Odell himself in a bind, almost guaranteeing he will be left behind. Sitting in a McDonald's in southeast Houston, this wiry kid full of nervous energy seems unaware of the odds he faces when he gets his first crack at the high school exit exam next year. His odds are bad because the Texas Education Agency has done something extraordinary. It created a high-stakes exit exam that almost perfectly predicts one thing: race. Edwards is African-American. According to field tests of the Texas Assessment of Knowledge and Skills, he has an 8% chance of passing. His grade-point average could be 95 (he admits that it's "mostly B's and C's"), but in a trial run of the test 92% of black kids failed. As a result, the test is being tweaked and scores will ultimately be curved. The trial tests predicted a disaster for black kids. And if Odell fails the Texas Assessment of Knowledge and Skills, he doesn't get out of Wheatley High. He gets a couple of re-takes. But what are the odds that a kid officially designated a failure after eleven, then twelve, then twelve and a half years of public education will come back for that third test in the summer after high school?

Odell works twenty-five to thirty hours a week at McDonald's and lives with his mother and stepsister. He'd like to get out of fast food but likes the money. He wants to buy a car and says maybe he'll go to Houston Community College -- at a campus that just opened in an abandoned strip mall on Martin Luther King Drive.

It's the American teenage dream, on a modest scale.

Here's a young African-American man of limited means who's always attended public schools where his minority was the majority. He's the guy George Bush must have had in mind when he talked about "the soft bigotry of low expectations." Bush can say what he wants to about ending that invisible bigotry, but he has helped stack the deck against Odell Edwards. Odell's school faces budget and staff cuts -- at the same time that President W.'s education law is demanding much more from Odell.

He'd have a better shot if he lived in Massachusetts. They spend money on public education there. In Texas we do schools on the cheap. "You can't say throwing money at public education won't work," an East Texas senator used to say. "Because we've never tried it."

It's going to take a heroic effort for Odell Edwards to cut loose from fast-food counter culture at McDonald's.

Enron Education

Here's how the rest of you got fooled.

You were told the No Child Left Behind law is the Texas model of competency testing gone national. That's not exactly true, and if it were, it wouldn't be good. For decades the Great State has served as the National Laboratory for Bad Policy.

In truth, the No Child Left Behind Act Bush got passed in January 2002 is not the Texas education model imposed on the nation. It's the Texas model with bells added to bring on the far right and whistles added to attract congressional liberals, and insufficient money to pay for any of it. And it was signed into law at a time when our public schools are being slammed by huge state-budget deficits.

As full-time residents of the state that gave you tort reform, H. Ross Perot, and penis-enlargement options on executive health plans, we're obliged to warn you that if Dubya Bush had exported "the Texas Miracle," the country would be in deep shit. In public education there was no Texas miracle. The last Lone Star miracle we know of was the time the face of Jesus appeared on a screen door in Port Neches, and that's been more than thirty years.

Linda McNeil is a professor at Rice University, codirector of the Rice Center for Education, former high school English teacher, a past vice president of the American Educational Research Association, and author of Contradictions of School Reform and numerous papers published in scholarly journals. In other words, not the sort of person the Bushies want meddling in public-education policy. After all, she has never published anything advocating phonics, and she has no real ties to the corporate world.

McNeil does use a corporate metaphor when talking about education reform in Texas -- in particular when describing the system the Texas Education Agency uses to track progress on the standardized tests our state's kids have been taking for about ten years. This is the system that supposedly authenticated the miracle in Texas public ed. McNeil likens it to a local company housed in a sleek corporate tower a few miles north of the ivory towers at Rice University.

"Enron," she said.

"You've seen newspaper accounts that explain how Enron used a single indicator to show how well the company was performing," McNeil said. She went on to explain that the average scores on Texas' standardized tests are like Enron's stock price -- inflated and manipulated. Profits and successes were reflected in stock price. Debts and losses were carried on a different set of books. McNeil believes that placing so much emphasis on kids' scores, and linking the scores to the jobs and cash bonuses of school administrators, corrupted the system. Just as Enron's focus on stock price corrupted the company by encouraging every employee to do everything possible to keep the stock price climbing, school administrators were pressured to use "any means necessary" to pump up test scores. Everything from replacing good curriculum with test practice drills to dumping weak students likely to be a liability to the school's ratings.

McNeil has worked with two other professors. Angela Valenzuela teaches in the College of Education at the University of Texas. Walt Haney is a displaced Texan from Corpus Christi, now on the faculty of Boston College. The three profs are persistent empiricists, always citing statistics about academic performance, always studying the effect of policy on the children in the classroom. (It does seem odd that Bush's first Texas education commissioner, Mike Moses, has taken up with these three education Cassandras, running around the state screaming, "The scores are falling!" Moses is now superintendent of schools in Dallas, a minority school district about to be overwhelmed by the high-stakes test mandated by the education law Bush pushed through Congress.)

Working together, the three professors of education found that bogus test scores are only one of two ugly truths about education reform in Texas. The other, linked to test scores, is the dropout rate -- one of the highest in the nation.

They started by asking why scores on the tests controlled by the Texas Education Agency steadily increased, while scores on national tests not controlled by the agency barely moved. If the state's standardized-test scores climbed over ten years, then scores on the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) and the American College Testing Program (ACT) should have increased with them.

They didn't.

Average scores on the state standardized tests showed healthy gains. Average scores on the college-board SAT and ACT showed meager gains. By 2002, after ten years of testing, students in Texas were doing great on the state tests. But they ranked forty-seventh nationally on college-exam scores. (We beat out North Carolina, Georgia, South Carolina, and the District of Columbia.)

The SAT and ACT scores would be even lower if the weakest students didn't drop out of Texas high schools.

Disappearing Children

"We disappear our kids," McNeil said, a usage normally heard in connection with Central American death squads. Many children -- far more than 50% in the cities -- who enroll in the first year of high school in Texas don't make it to graduation. There's an institutional incentive for them to leave. If test scores are low, schools are rated low-performing. In low-performing schools, principals lose their jobs. Tests as a single criterion to evaluate schools provide an incentive for principals to disappear weak students to keep their campus test scores high. (This is not just about job security and money. Most public-school faculties in Texas will jump at the chance to push an incompetent principal out the door, but teachers will also fight a system that drives away dedicated, competent principals working with limited resources and against great odds.)

The low-performing students encouraged to go quietly are mostly Latino, African-American, and students with limited English proficiency (LEP). After they leave, the Texas Education Agency cooks the books. In 2001 the agency released dropout figures -- all under 4%. But the conservative Manhattan Institute came up with a dropout rate of 52%. The Intercultural Development Research Association, a liberal education-advocacy group based in San Antonio, has tracked dropout numbers for ten years. It says the rate is 40%, which translates into more than 75,000 teenagers each year. A state senator from Corpus Christi calls the TEA dropout numbers "treasonous." The Dallas Morning News reports that the feds threatened to cut dropout-prevention funds because the Texas formula for calculating dropouts is so inaccurate.

McNeil and her Rice University researchers found a Texas Education Agency accounting system that would have done Arthur Andersen proud. Principals desperate to keep kids away from tenth-grade exit exams discovered a Never-Never Land, a special place where kids never make it to the tenth grade and never take standard exams. All they need is a waiver from the state to allow kids who failed one course in the ninth grade to stay there. These "technical ninth-graders" sometimes stay on ninth-grade enrollment ledgers for three years -- if they stay in school. Sometimes, McNeil wrote, they're discouraged from taking the course they failed, which would allow them to advance.

In one Houston high school with a student body of 3,000 only 296 kids took the tenth-grade test. Barring fluctuating fertility rates, there should have been between 700 and 750 students in the tenth grade. "All our children will be tested. No one will be excluded," claimed Houston superintendent Rod Paige, the year before Bush named him secretary of education.

The kids who stick around for the tests aren't exactly reading Faulkner and solving quadratic equations. Listen to almost any teacher in the state of Texas and you'll hear a story about valuable classroom time lost to drills that prep students for the test. About art teachers compelled to drill a half hour each day for the test. About English teachers required to start every class with a drill that teaches students to underline the central ideas in short paragraphs. About testing consultants who charge a stiff fee to help principals get campus scores up by telling teachers to focus all their drilling efforts on "the bubble kids" -- the ones in the small "bubble" of scores just below passing. (Forget the children at the bottom -- you'll never get their scores anywhere close to the magic passing number.) About a small school district spending $20,000 on prep handbooks for the TAAS, the recently replaced Texas Assessment of Academic Skills.

Heard about Guerrilla TAAS? A neat little test-attack-skill handbook with a camouflage cover. "Cool," say the kids. "Cami."

There's more.

The guerrilla consultants show up at schools to lead Guerrilla TAAS pep rallies. They wear camouflage combat fatigues. Even the principal and assistant principals get to suit out in camouflage -- all included in the price of the Guerrilla TAAS package.

"Hey, guys, we're going to teach you how to kick this test's butt."

Some miracle, huh?

Is there a papal nuncio in the house? ![]()

From BUSHWHACKED by Molly Ivins and Lou Dubose

Copyright © 2003 by Molly Ivins and Lou Dubose.

Published by arrangement with Random House, an imprint of Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House Inc.

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.