Matter Over Mind

The Future Rolls Toward Dripping Springs -- Riding Bulldozers and Money

By Rob Curran and Amy Smith, Fri., Sept. 21, 2001

In the late Seventies, when Austin was still clinging to its small-town roots, a youthful group of visionaries decided it would be cool to box up their households and start a new community in the hills southwest of the city. Starting a new community is not like starting your own band. Plans for the big move were crafted over a period of many months at a collective on Nueces Street at 28th, near the University of Texas campus, where students, recent graduates, and young professionals would gather for potluck dinners and group meditations.

The concept crystallized in 1980, with the formation of the Ideal Village Development Cooperative of Austin, a governing board of sorts that integrated a business plan and some real estate savvy with the teachings of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, the spiritual leader whose name became a household word in 1968, when he introduced the Beatles and Mia Farrow -- and the rest of the world, for that matter -- to the wonders of Transcendental Meditation. Mindful of the Maharishi's vision of creating "ideal villages" around the globe, DevCo, as the cooperative called itself, raised funds through personal contributions and others committed to the project. Eventually the cooperative found its Heaven on Earth -- about 900 acres of the old Christal Ranch, off FM 1826 in northwest Hays County. "It seemed so far from Austin at the time," Carol Hardin, one of the early pioneers, recalled of the vast, rolling frontier, which today is mere minutes from the Circle C golf course in Travis County.

Over the years, the meditating community of Radiance matured, with DevCo maintaining its economic vitality by selling large lots in the adjoining communities of Goldenwood and Goldenwood West. The three low-density subdivisions each have their own neighborhood associations, but the communities share a winding thoroughfare off FM 1826, as well as a single wooden sign -- "Goldenwood" -- that greets visitors at the entrance. Not all the residents practice Transcendental Meditation, but those who do are welcome to meditate mornings and evenings in the quiet of the Golden Dome -- a large, fairy-tale-like structure set in a small clearing on the far edge of Radiance, one of only a few TM colonies in the United States. Here, deer and rabbits are as much a part of the scenery as the hundreds of cedar and live oak trees that were spared during construction of the community.

Meditators and non-meditators alike must have felt an odd karmic shift in the universe the day they learned that the Dripping Springs City Council had brokered a secret deal with Cypress Realty, a private investment and development company that has designs on 2,724 acres of property next door, part of the former Rutherford Ranch. Neighbors say they had no clue the deal was even being negotiated, nor were they aware, in the weeks before the document was officially sealed on April 24, that the wheels had already been greased. By then, the city council had unanimously approved the creation of a special water district for the development and given the nod to City Attorney Rex G. Baker III to execute the agreement with Cypress. The neighbors remained unaware of these events until early May, when a certain bill in the Texas Legislature -- to create a special water district for the Cypress site -- popped up on their radar. "That's when the shit hit the fan," one resident recalled. That's also when Rep. Rick Green and Sen. Ken Armbrister saw their joint legislation -- which had moved swiftly, quietly, toward winning final approval -- come to a screeching halt.

Admittedly, the Goldenwood and Radiance neighbors seldom followed the municipal affairs of sleepy Dripping Springs, largely because they felt removed from local politics, living 12 miles outside of the city but still within the city's extraterritorial jurisdiction. "We were asleep," a Goldenwood resident acknowledged. "We found everything out after the fact, and then we had to work backward to figure out what had happened."

After the initial shock wore off, the residents of the three communities hunkered down and got organized. They began meeting with Stephen Clark, the Cypress developer, and the two sides say the meetings have been cordial and somewhat productive. Clark, for example, says he's about 90% sold on the idea of requiring native-plant landscaping for the development and about 50% convinced that a rebate-incentives program would encourage prospective residents to install rainwater-harvesting systems on their property. "They're so nice," Clark says of his new neighbors. "When they ask me to do something it's hard to say no."

Not everything is going as smoothly as Clark suggests, however. The residents, for example, feel strongly that the project should have third-party oversight, while the developer feels just as strongly against. At any rate, until he secures environmental clearance from the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, Clark says he's uncertain whether he'll develop according to his existing plans -- plans that call for a subdivision of single-family homes, townhomes, some commercial property, a school, and the project's prized jewel: a 27-hole golf course.

The Cypress project has also caught the attention of area environmentalists: Not only is it the largest of some 19 platted developments planned for northern Hays County, it sits directly atop the heart of the Edwards Aquifer -- the porous recharge area where water seeps below ground to Barton Springs, the main drinking water source for 45,000 residents in northern Hays and southern Travis counties.

Market Regionalism

While neighborhood leaders say Clark has been willing to meet with them and consider their concerns, Dripping Springs officials have been less responsive. Rob Baxter, president of the Goldenwood Property Owners Association, said he and a group of residents had rather boldly asked the council to rescind and revise the agreement so it would be more palatable to all sides. The council declined. "Nobody likes to be told that they're doing something wrong," Baxter says. "But that's what we're doing, and that's what makes us unpopular." Radiance resident Roger Kew makes no excuse for the group's unpopularity: "We feel as residents that the council members had a duty to safeguard our interests. They did not."

At least one council member acknowledges that the city could do a better job of alerting residents of issues that may impact them. "We post the item, but do we do an adequate job of notifying residents? Well, I could debate that," Council Member Mike Firle said. "There might be something published in the [Dripping Springs Dispatch], but unfortunately, being a small town, maybe 50% of the residents get the paper, and then maybe 50% of them read it."

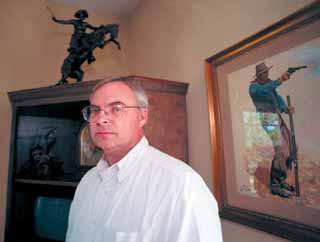

Baker, the attorney who negotiated the Cypress agreement in the city's behalf, defended the process leading to the signing of the document. "There's no cloak and dagger, there's no back-door deal," he said. Goldenwood and Radiance residents will have other opportunities to weigh in on the project, he added, because Cypress still must submit its master plan for approval. Baker also brushed off whispers about his alleged role in the real estate transaction between Rutherford and Cypress. He is named as a trustee on the deed and deed of trust documents. But anybody can be a trustee, he said, explaining that the Rutherford lawyer in Houston most likely listed him as a trustee because his title company handled the land exchange, just as his company handles hundreds of land exchanges. "I happen to be put into a lot of deeds of trust, but I don't represent the Rutherfords. I don't have business with either [Rutherford or Cypress]."

The appearance of Baker's name on a deed of trust, regardless of how it got there, is illustrative of a man who wears many hats in Hays County. By most accounts, Baker is among an elite group of Hays County leaders making key decisions on development issues affecting one of the fastest-growing counties in the United States. Additionally, he handles the city's legal affairs, runs a private law practice, is a co-owner of Southwestern Title Company, and serves in an elected position as a Hays County justice of the peace.

Moreover, Baker is spearheading an effort to devise a "regional solution" for protecting surface water and groundwater in Hays County's sensitive Barton Springs Zone. Dripping Springs Mayor Todd Purcell, Austin engineer George Murfee, and County Judge Jim Powers are helping Baker in the endeavor, which curiously shuts out other major stakeholders in the area -- notably the Barton Springs/Edwards Aquifer Conservation District. In a July 30 letter to the conservation district, Judge Powers basically advised board president Craig Smith to shelve a separate environmental plan in the works for the Barton Springs Zone. "At this time I see no need to move forward with your Habitat Conservation Plan," Powers wrote, "as I believe the local entities with jurisdiction of land development are best suited to develop this regional solution."

Smith responded in an Aug. 15 letter to Powers, reminding him that the conservation district is responsible for regulating pumping activity and safeguarding the quality of the water for well users and the endangered Barton Springs Salamander. The regional planning process, Smith wrote, should include a broad cross-section of stakeholders, not just a small group led by City Attorney Baker. "If we proceed as we have been, the aquifer will become unusable," Smith later told the Chronicle, referring to a recent Fish & Wildlife report detailing the gradual degradation of Barton Springs. "But there are things that can be done -- it's not inevitable that the aquifer will be unusable."

The far-reaching report, a draft biological opinion released in late July, faulted sprawling developments -- and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's lack of environmental enforcement -- for the high levels of toxins and other pollutants in Barton Springs (see "Mercury, Cadmium, Arsenic, Grease ...," in the Aug. 3 Chronicle). That kind of news is just one reason the Cypress development is drawing so much attention, particularly since a Fish & Wildlife opinion could make or break the project. David Frederick, the regional administrator of Fish & Wildlife in Austin, would not comment on how his agency might rule on the environmental fitness of the Cypress development, except to say the two sides are talking.

Clark, the Cypress founder who moved the company's home base from Houston to Austin about a year ago, bought a section of the giant Rutherford Ranch in the spring of 2000, essentially picking up a portion of the tract that California-based Newhall Land & Farming Company abandoned after pulling the plug on its mega-development plans and heading back to the West Coast. Once Cypress entered the picture, George Cofer, a longtime environmentalist and founder of the Hill Country Conservancy, a land acquisition and preservation outfit, decided to make a bid on the property. With the city of Austin kicking in some land-acquisition bond money toward the down payment, Cofer thought the Conservancy had a good shot at negotiating a fair purchase price for the property.

But Cypress' Clark, who had paid about $11.3 million for the land, drove a hard bargain. Finally, negotiations stalled. "We couldn't raise the money in the timeline that Steve wanted," Cofer said. But Clark said as recently as late August that he's still willing to consider selling at least a portion of the property for conservation. "We don't feel obligated to turn our land into a park," Clark said, "but we've been pretty darned open to [the Conservancy's] interest in the property."

While the city of Dripping Springs gave Cypress the authorization to build 2,700 houses and a 27-hole golf course on the land, Clark says, "That is the limit ... we have not submitted a plan to anybody for 2,700 units. One was close, but that plan would still have to meet Fish & Wildlife Service restrictions."

Cypress also must meet the federal agency's standards to acquire a surface water supply by hooking into the Lower Colorado River Authority pipeline, a controversial water line that environmentalists opposed on grounds that it would drive development over the aquifer. Potential connectors to the pipeline must work through an extensive Fish & Wildlife checklist, ensuring that runoff will not reach the Edwards Aquifer without filtration for pollutants. In June, the LCRA announced that 155 connections at Rutherford Ridge, a subdivision located south of the Cypress development, had passed the Fish & Wildlife standards and had qualified for service from its surface water pipeline. "This is still contingent upon the results of the [Fish & Wildlife] Environmental Impact Study," said LCRA spokesman Bill McCann. "We have not signed any contract in Rutherford Ridge."

Environmentalists have accused the LCRA of pandering to business interests like Clark's. "In all the planning done for the pipeline," said Bill Bunch, executive director of the Save Our Springs Alliance, "the LCRA was envisioning selling a lot of water to the Rutherford Ranch area." McCann responded that anyone seeking connections is referred to Fish & Wildlife for approval, but he added that without a ready supply of surface water, a development like Cypress would have to rely on water directly from the Edwards Aquifer.

LCRA seems to be following Hays County officials' apparent belief that developments simply can't be stopped. "In Texas, people tend to look at property rights first and natural resources second," observed Jim Camp, who represents Hays County on the conservation district board. "The people in a position to do something proactive to protect the aquifer are the ones who are the most resistant. Their feeling is, 'If Austin has it, we don't want it'; if Bill Bunch says it's good, they say it's bad. But if everybody keeps popping straws into the ground, and if we have the kind of drought that we saw in the Fifties, we could see Barton Springs go dry. And Austin can say goodbye to the crown jewel of the city."

From Disney World to Dripping Springs

On May 24, Clark attended a special meeting of the Goldenwood Property Owners Association, along with residents from Radiance and Goldenwood West. The group met at the state-of-the-art "green" home of Carol and Ken Hardin, longtime practitioners of Transcendental Meditation. The Hardin home, the first of its kind in Texas, was built using the natural laws of Sthapatya (sha-pat-ya), what Maharishi Mahesh Yogi calls the art of correct placement for optimal living. The home is energy efficient to the core and includes a solar hot water heater and two 17,000-gallon rain-harvesting tanks. The idea behind inviting Clark to the home, says Carol Hardin, was to show him how the investment of energy-efficient systems can save money in the long run. The recent rains have already proved that much, she says, because both tanks will provide enough water to serve her family's needs for the next four months.

Clark, apparently trying to assuage the neighbors concerns about Cypress, told the residents that he wished the residents could see one of his earlier showcase projects: the Abacoa development in Jupiter, Florida. Coincidentally, neighborhood leader Rob Baxter had some business in Orlando, Florida, a few days after the meeting with Clark. Baxter visited Abacoa, and found large tract homes on small lots and cluster-housing on yardless lots -- for an average 50% impervious cover. As Baxter describes it, the main source of greenery in the neighborhood was a golf course: "It looked a bit like Disney meets the Stepford Wives." (Abacoa has a Web site at www.abacoa.com.)

"Rutherford is at totally opposite ends of the spectrum to Abacoa," Clark told the Chronicle. "Abacoa was an ultra-dense project; Rutherford will be a moderate-density project. We think the [present] Hays County tone is a huge marketing plus." Clark added that, with the guidance of Fish & Wildlife, runoff from Rutherford will contain fewer impurities than runoff from Goldenwood. That claim is debatable, however, because the Goldenwood and Radiance communities have less impervious cover and less density than the proposed Cypress development.

Baxter said that while in Florida he questioned the Jupiter City engineer as well as that city's planning and zoning commission and found that, according to city records, Cypress Realty had no connection to Abacoa, which was actually developed by George DeGuardiola. "We got involved toward the end of the planning process," Clark explained. "We are half-owners of Abacoa, we have a project manager over there [George] and he represents us." DeGuardiola told Baxter that Cypress had funded the Abacoa project without taking part in the planning process. These conflicting reports prompted Baxter to investigate further. "If something as simple as this is cause for obfuscation," Baxter said, "imagine what may happen in our own back yard."

There were other discoveries, too. With the help of a Jupiter city engineer, Baxter compared the development agreement between Ritz-Carlton and the Jupiter City Council to the development agreement between Cypress and Dripping Springs. The Jupiter agreement appointed an independent biologist with powers to enforce ecological measures during the course of the project. A trust fund for the protection of turtles in the area was also instituted. The Dripping Springs agreement, by stark contrast, cleared the way for Cypress to appoint its own engineer to oversee the project and ensure that the city's standards are met. The agreement makes no mention of the Barton Springs Salamander or other species dependent upon the Edwards Aquifer. And neighbors who draw water from the aquifer expressed concern that the agreement made no mention of their wells.

Baxter and other residents were also puzzled by the Dripping Springs agreement's treatment of permit fees. The council agreed to a flat $1 million "master development fee," instead of the standard 0.5%--5% in sliding construction fees, which were likely to accrue millions more during the Cypress project. What was City Attorney Rex Baker thinking, the neighbors wondered, when he convinced former Mayor Wayne Smith and the Dripping Springs City Council to sign this agreement? Some area residents suggested that, as part owner of a large title company in Dripping Springs, Baker might have a personal interest in maximizing development in the area. Baker denies this. "I find that silly," he said. "I don't go out and recruit developers. Will my title company benefit from development? I don't know. We've been around a while, so we do quite a bit of closings." Baker added that if he were more interested in development interests he would be representing developers and making a lot more money than what he gets from the city.

Goldenwood and Radiance residents don't believe Baker had environmental interests in mind when he negotiated the agreement. The document states that Cypress Realty may cover up to 25% of their property with cement, roofs, or tarmac; the Fish & Wildlife Service recommends no more than 15% cover over the Edwards Aquifer. (Baxter is quick to note, though, that under the city's existing ordinance, "Cypress could have developed this out at a lot higher density.") And Erin Foster of the Hays County Water Planning Partnership questions whether even these loose limits will hold, noting the weak provisions covering breach of contract. Either party is entitled to take legal action in case of a breach, says Foster, herself a real estate professional. "But there are no specific remedies, no specific defaults mentioned."

The Green Legislator

Of course, no one had yet examined the Cypress agreement, much less heard of it, until residents caught wind of Rep. Green's House Bill 3641 and Sen. Armbrister's Senate Bill 1771, both of which sought to establish Cypress Realty's portion of the Rutherford Ranch as the Hays County Water Control and Improvement District No. 3. If ratified by a popular vote, "improvement districts" enable real estate developers like Clark to have sovereignty over the assigned area. For the purposes of road and utility building, the district board may issue government bonds to investors and levy taxes from residents of the district to help repay the bonds. But another water district bill for developer Gary Bradley's district gives a developer more freedom of operation along with investment appeal. In Green's mind, though, his legislation had the very best intentions. "The development is going to move forward with or without the district," he said. "But this was a way to make sure we had a good development, and that we have green space and buffer zones."

Despite an ongoing investigation by Attorney General John Cornyn into abuse of special taxing districts, and the AG's call for revisions to the law in the next legislative session, Clark believes that Texas improvement districting works well. "You get rid of Municipal Utility Districts, and that has a very big impact on affordability." He admits that developers often set people up in mobile homes on their land to vote districts into existence -- just one of several shortcomings that The Dallas Morning News pointed out in a recent series on special taxing districts. To Clark, moving a few people into trailers on private land so they can vote to create a district is a "hokey" part of an otherwise "smooth" system.

Green said he agreed to sponsor the Cypress bill at the request of Dick Brown, a longtime developer-lawyer hired by Cypress. In a late-in-the-game response, the Hays County Water Planning Partnership retained lobbyist Mike Kelly to try to defeat Green's bill. "It was the breadth of the legislation that raised so many red flags," Kelly said. "It provided such broad powers to the district, and it looked as if it might have annexation powers." At the time Kelly came on the scene, the two bills were sailing effortlessly through the legislative process. Armbrister's bill had survived a Senate vote; Green's had passed out of the House Natural Resource Committee without opposition, and been sent to the Local and Consent Calendars Committee -- where bills routinely win passage without ever reaching the House floor. At that point, Rep. Lon Burnam, a Fort Worth Democrat, intervened. "He kind of blindsided the deal at the last minute," Green said recently. "Then all the erroneous e-mails started floating around -- there was so much misinformation out there."

"That's like the kid getting caught stealing from the cookie jar and then complaining about it," Burnam responded. "I considered Rick Green's legislation a trashy water-hustler bill that couldn't stand the light of day if it had made it to the House. I told him he could either pull the bill down, or I would talk about it for 10 minutes." Green pulled the bill down. (He had better luck with Hays County Water Control and Improvement districts No. 1 and No. 2, allowing Capital Pacific Holdings, a Bradley-affiliated company, to acquire water districts for 1,600 acres of the Foster Ranch, along U.S. 290 and the new LCRA pipeline. But another freshwater district legislation for Bradley's Spillar Ranch didn't survive.)

Questions? Ask the 'Free Market'

On June 5, Goldenwood and Radiance residents presented the Dripping Springs City Council with a list of queries pertaining to the Cypress agreement. Why, the residents wanted to know, did the council decline to include demands for environmental impact studies, as the city of Jupiter had required in its agreement? And since the $1 million "master development fee" was linked to the revenue from district bonds, does the failure of HB 3641 render Clark free of financial obligations to the city?

Most importantly, the residents questioned why the council made no attempt to include their voices in the Cypress agreement. "The absolute worst thing about the agreement is that it was done in a vacuum, and purposely so," Baxter told the Chronicle. "Agreements that are as potentially far-reaching as this must have citizen input."

It's not likely that citizen input would have influenced City Council's decision. In any case, as of press time, the countil has not replied. As Jim Camp noted earlier, those who are in a position to tighten regulations in fragile areas are the very ones throwing up their hands in the face of developments spreading like flame across the Hill Country. As it turned out, Camp didn't have to prove his point. City Attorney Rex Baker did it for him: "The thing that decides development is not the City Council and not the city attorney. I think no matter what ordinance is in place, market forces will ultimately have the final say." ![]()

Onward Through the Hays

County Population:

1990: 65,614

2000: 97,589

Growth in 10 years: 48.7%

Est. amount of undeveloped land in northern Hays County: 154,000 acres of environmentally sensitive land

Number of subdivisions planned in northern Hays County: 19

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.