Man Writes About Woman!

Is Dagoberto Gilb Girl-Crazy?

By David Garza, Fri., Jan. 26, 2001

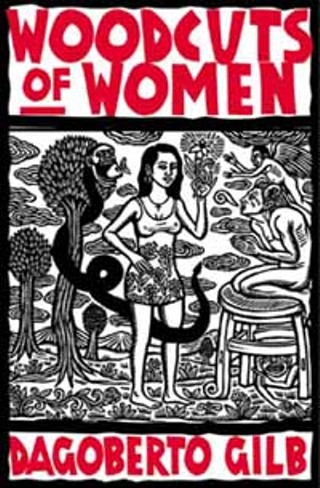

Woodcuts of Women

by Dagoberto GilbGrove Press, 167 pp., $23

Readers of Dagoberto Gilb's new collection of stories may get the impression that the author is a macho man's man. Just about every story in Woodcuts of Women, after all, tells of male characters who suffer and sweat through long desert hours for the bitter perfume of sex. There's the newspaper editor who slowly unravels in his attempt to win back his wife, and there's the day laborer who drinks his way into bed in the evening. Then there's the author himself, whose jacket photograph proudly reveals a solid neck and a blunt face that would make the thunderous gods of mythology jealous. "A union construction worker for over twelve years," his impressive biography boasts. But to label Gilb's effort at writing effectively and seductively about women an exclusively macho affair would be facile, if not plain lazy. The 10 stories in this impassioned collection not only teem with characters of genuine human complexity, they also prove the author to be a thoroughly provocative voice in contemporary American fiction. At their best, it turns out, the stories in Woodcuts of Women create a refreshingly accurate and comprehensive model for the psyche of the heterosexual Chicano male -- the trite and overblown notion of machismo, and of masculinity itself, is replaced with the decidedly less villainous aura of real emotional and sexual desire.

"Women's perfume is everywhere, and I'm dizzy when I'm there," marvels the teenage narrator of Gilb's first story "Maria de Covina." With that elegant statement, and with its paragraph full of the narrator's detail about the joy of dressing in silk suits ("getting all duded up"), Gilb indicates that he knows how to play the main tricks of his fiction. By writing about women, by giving audible voice to what men do for the attention of women, he is ultimately creating powerful "woodcuts" of men.

That's not to say that on some level this book shouldn't be judged quite literally by its cover. The woodcuts by Artemio Rodriguez that accompany Gilb's fiction play with and interchange the notions of the sacred and the forbidden in a sort of temporal vacuum. There are naked women, and women in the act of sex, and women, too, who just may be sex itself. Take, for instance, the colossal woman depicted by Rodriguez at the opening of the story "Bottoms." She stands in a loose bikini top by the pool, hunched over so that her belly flattens to an odd plateau. The purity of her sexuality is marred somewhat by the tattoos on her shoulders, but interestingly enough, one of those tattoos depicts a double-pierced heart. That seemingly Catholic allusion becomes more ironic still once the reader enters the story -- it turns out that the woman accidentally becomes a Jezebel at a public pool frequented by a heterosexual young writer who is struggling to finish a book review dealing with the sexual roles of dominance and submission assumed by homosexual men. These issues, of course, will ripple and splash in the immediate life of our distracted male protagonist.

Despite the fact that Gilb is able to create a worthy plot and character for this woman, her most intriguing moment is in the instant when she enters the young writer's mind for the first time: "She is such a big woman. Huge woman. Gigantic in almost all aspects. Is she over six feet tall?" The mesmerizing girl then becomes a composite of some rich and frozen visual cues, a fact which makes the woodcutting theme both appropriate and effective. The question that remains for both the reader and the male character is whether the women of Gilb's work can be -- or even should be -- absorbed as more than fleeting and singular tastes of the sublime.

There are significant spots in the collection, though, where both men and women are presented not as objects of pure abstraction or lovesick philosophers but as physical and mental wrecks. The story "Shout," for instance, is effective in its assault on the reader because the author successfully re-creates the lives of a struggling family living in unbearably close and sweltering quarters: "He carried on in Spanish, hijos de and putas and madres and chingadas. This was the only Spanish he used at home. He tossed the hard hat near the door, relieved to be inside, even though it was probably hotter than outside, even though she was acting mad."

These moments of pathetic violence and squalor tend to erupt from suppressed desire or from the wretched results of desire satisfied (as is the case in "Shout," which shows the main couple weighted down with several poorly tended children). As pieces of fiction, though, they function brilliantly under Gilb's flair for the imagistic and allegorical which he finds in both the human body and in the hues of a barren landscape. He opens his most successful story, "Hueco" with an appropriately repulsive image of a domineering landlady: "Mrs. Hargraves's tongue was blood-red with deep blue veins on its underside. I knew because she was smiling, and lots of those teeth in front weren't there, and her tongue licked the top gaps." No woodcut necessary there, thanks.

The stories also succeed with their ambivalent relation to space and location. Throughout most of the collection, the reader is aware that the events are taking place somewhere in the American Southwest, either along or near the Mexican border. Gilb, who teaches creative writing at Southwest Texas State, seems to relax and stretch out over the warm expanse of land between the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific Ocean with listless comfort and ease. True, there are portions of the text in which action is clearly tied to a marked locale -- "Mayela One Day in 1989" begins with the sentence, "I'm in a city called El Paso," and ends with, "I am in El Paso. It is 1989." But he continues to describe the city and geography itself as "imaginary concepts," and the larger portion of the work remains unmarked, as if the prose itself were feeling the drifting nature of the young writer from "Bottoms": "That my life is pushed by wind, sometimes calm, sometimes stormy, and while I navigate its current, I don't know its direction."

Gilb creates his aesthetic and political forum in that accidental space where his characters wander and interact. The above-mentioned story "Hueco" follows the life of a manual laborer named Fernandez who rents a furnished apartment from the haggish Mrs. Hargraves and struggles to lead an independent life in spite of her intrusions. Hargraves' mother has previously died on the same bed which Fernandez now occupies, and she finds the thought of anyone having sex on the bed unacceptable. Fernandez, though, is bewitched by the pale blue colors that mark the apartment as well as the hueco (the deep depression) left by the weight of Hargraves' mother on one side of the mattress. That depression becomes a forbidden and sacred hollow where he consummates his relationship with a girl named Yvette. Is that place tainted by the sweat of Fernandez's sex, Gilb seems to ask, or is it made more holy, more cavernous and allegorical?

That tainted and sacred space exists in all manners and dimensions throughout Gilb's work, from the tightening physical vacuum between two people in the motion of sex to the conceptual impasse between the United States and Mexico. The stories in Woodcuts of Women explore this dangerous zone and seduce the reader into the knowledge of the sanctity of intercourse between any number of elements, not least of all that between men and women. Can you blame men for being entranced by this space, by the aroma and the flavor of it? Certainly not, this collection of fiction argues. And as the exploration of women serves to illuminate much about the nature of men, the unraveling of the work shines its own interesting light on the distinctive author himself. ![]()

Grove Press, the Continental Club, and Resistencia Bookstore will host a publication party for Woodcuts of Women and Dagoberto Gilb on Wednesday, Jan. 31, 6:30-9pm at the Continental Club (1315 S. Congress). Free and open to the public.