From Here to Eternity

The Story of the Clash

By Jerry Renshaw, Fri., May 19, 2000

The Clash haven't aged well. Mick Jones is suffering from a serious combover, trying to deal with his vanishing hair. Paul Simonon has lines on his face you could plant soybeans in and the look of an average Joe punching a time clock somewhere. Topper Headon's appearance is downright startling; he's shriveled like an old man or someone who has suffered from some nasty illness (like, maybe, a drug habit) for a long, long time. Joe Strummer has held up best, his snaggly dental work fixed and his pompadour still intact. The band has officially scotched rumors of a reunion until now, though word has it that all four will reunite in June to play an Ian Dury tribute at London's Brixton Academy. Too often, though, it's rather pathetic to see a band back together, 20 years older and 30 pounds heavier, slogging through old favorites like draft horses working the plow -- holding their guitars like shovels rather than machine guns. Rock bands weren't meant to have a great longevity; just look at 1976-era Elvis.

With Watergate, inflation, busing, Jimmy Carter, the Cold War, and the Ayatollah, Seventies America wasn't the stoner's paradise shown on revisionist fare like That '70s Show; by and large, things went along in a sort of earth-toned, earth-shoed woodgrain plastic drift. Seventies Britain, on the other hand, was a dreary place, light-years different from Tony Blair's touchy-feely, Millennium-Domed UK2000. The Clash spoke directly to the issues afflicting their native land: unemployment, racism, police oppression, the dole, drugs, war, corruption, and decay. They looked around and saw boarded-up windows, Ford Cortinas up on blocks, trash in the streets, hopelessness and frustration everywhere.

The Clash homed in on their concerns like sharpshooters, articulating much more clearly than the splenetic sputterings of latter-day hardcore bands like GBH and the Varukers, or the confused "Anarchy now!" vegan muddle cooked up by hippies with punk haircuts like Crass. The Sex Pistols went more for shock value for its own brainless sake; the Ramones sang revved-up pop songs about glue and girls, with politics being the furthest thing from their Carbona-crazed minds. The Clash was the first politicized punk band, and what's more, they were the first act out of the gate that could actually compose and play smart, articulate songs.

Plenty of Johnnys-come-lately sneered "Clash equals Cash," and pointed out that the band didn't really hail from the working-class roots of Brixton bootboys like Sham 69 or the Cockney Rejects. True enough: Strummer had a middle-class upbringing as the son of a diplomat, while Simonon drifted into art school after a rather unsettled childhood and adolescence. Jones, on the other hand, lived with his grandmother after his parents' separation, going to rock shows at an early age as an escape.

The band's biography is certainly a case study of success being a band's worst enemy, the Clash imploding at a point when many bands would be coming into their own. Their epitaph, however, is what matters; Columbia Legacy's deluxe remastering/repacking of the Clash's entire catalog not only reminds us that the band gave voice to an entire generation of angry, alienated Brits, they also rocked with a ferocity seldom seen before or since.

When Mick Jones finally began attracting attention for his guitar playing, he was in a glam rock outfit, the Delinquents, complete with long hair, feather boas, and poncey trappings; in time he would meet up with Tony James (later of Generation X and Sigue Sigue Sputnik) to form the London SS. With a revolving-door cast of players including future members of the Damned, Chelsea, and PiL, London SS took the first stack-heeled, shambling steps toward punk, naming among their influences the Stooges, MC5, and New York Dolls, and in the process acquiring future Clash manager Bernie Rhodes. By 1976, London SS had fallen apart, and Jones found himself in a new band with guitarist Keith Levene and art-school dropout Paul Simonon. Simonon had spent much of his time hanging out with his West Indian pals and immersing himself in reggae, ska, and skinhead fashions, elements that would later be part and parcel of the Clash. Meanwhile, in another part of London, 24-year-old John Mellor was bashing away in pub-rock outfit the 101ers. The band caught the interest of Simonon and Jones, still in search of a frontman to round out their lineup.

"It was quite a scene," Mellor reflects in a recent documentary on the Clash, Westway to the World. "Fights breaking out, glasses shattering, dogs running about."

The three had an uneasy meeting one day in a dole queue (unemployment office, for you Yanks), with Mellor being approached with an offer to hook up with the incipient band. After sleeping on it, he assented, eventually dubbing himself Joe Strummer. Taking drummer Terry Chimes along for the ride, what would shortly be known as the Clash began a crash course in rock & roll. Wanting a different look, they splattered their clothes with paint, Pollock-style. Stencils provided agitprop sloganeering for their shirts and jackets, "Hate and War" being the ultimate rebuttal to the hippie-dippy "peace and love" claptrap.

"We were almost Stalinist in our approach," Strummer notes in a recent issue of Mojo. "Part of punk was shedding all your friends, everything you knew, everything you'd played before, all in a frenzied attempt to create something new -- which isn't easy at the best of times. We were insane, basically -- completely and utterly insane."

The Clash readily admitted what many other Britpunks would only grudgingly admit in hushed tones: The first Ramones LP was a huge influence on their playing, songwriting, and attitude that summer of 1976. Equally large in their musical purview was the reggae of Bob Marley, Desmond Dekker, Prince Far-I, and Junior Murvin. Jones and Strummer worked out a chemistry for giving ska and reggae the Clash treatment; rather than the rhythm guitar strictly playing the upbeat, Jones would play the downbeat and Strummer the up, giving the songs a choppy push-pull that worked beautifully and became one of the band's signatures.

It was the band's love of reggae that led to an early turning point for the group. At a summer carnival in London's Notting Hill, a full-scale race riot broke out, and the Clash found themselves in the middle of the tumult. With cars ablaze, police cracking heads, and bricks flying, the band solidified a reputation as street-level activists, true rebel rockers. Shortly afterward, Strummer wrote the band's first anthem, "White Riot," with its incendiary chorus, "White riot, I wanna riot, white riot, a riot of my own!" It was a manifesto, a call to action that said that it was time to stand up and be counted or else be trampled underfoot.

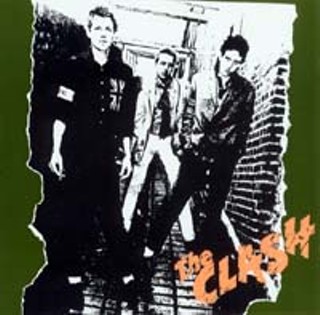

Soon, the band's full-length debut for CBS was in the works, and more than 20 years later, 1977's The Clash still stands as a remarkable snapshot of a nascent band beginning to hit a bristling stride. The torrent of vitriol that runs through songs like "Janie Jones," "London's Burning," "Career Opportunities," and "I'm So Bored With the USA" is simultaneously angry, hateful, and intelligent.

"White Man in Hammersmith Palais" pointed the way toward the West Indian groove that many future songs took, while summing up much of the band's complex political bent in a wholly unsentimental way: "White youth, black youth, better find another solution. Why not phone up Robin Hood, and ask him for some wealth distribution. ... "

The hard-boiled, razor-sharp insights of Strummer's lyrics got right to the meat of the matter, having more in common with the MC5's brand of realpolitik than Bob Dylan's hermetically sealed poesy musings. Throughout the album is a strong sense of songcraft, with arresting hooks and muscular verse-chorus structures that are as galvanizing today as they were in 1977. It's hard to think of a more powerful, committed statement of alienation, frustration, and rage than that album.

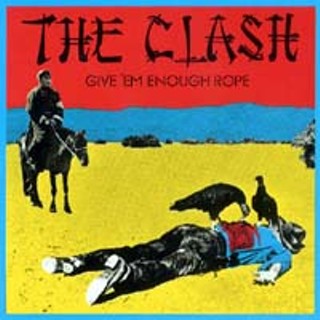

The higher-ups at CBS didn't see fit to release The Clash in the U.S. until 1979, deeming the LP's production too crude for American ears. Instead, sophomore slump Give 'Em Enough Rope brought the band its first domestic exposure in l978. Black Market Clash from 1980, a 10-inch EP, attempted to fill some of the gaps in the band's U.S. availability, but there were still songs available in the UK that never made it across the pond, and vice versa.

When the first album was finally released stateside, the label resequenced the songs, dropping "Protex Blue," "Deny," "48 Hours," and "Cheat" from the UK release in favor of "Clash City Rockers," "White Man In Hammersmith Palais," "I Fought the Law," and "Jail Guitar Doors." Columbia Legacy has smartly rereleased both versions, punching up the mastering of the originals (at least as near as I can tell by comparison to my battered vinyl copy).

Black Market Clash, on the other hand, is now Super Black Market Clash, expanding the 10-incher's nine tracks into 21; unfortunately, the resulting mix of material is somewhat uneven. More than a compendium of odds and ends, the reissue does include copious liner notes detailing each song's background and trying to clear up any back-catalog confusion.

By the time Give 'Em Enough Rope was under way in 1978, third guitarist Keith Levene had long since been ditched as dead weight. Chimes also fell by the wayside, the reason for his acrimonious billing as "Tory Crimes" on The Clash. Along the way, the band hooked up with journeyman drummer Topper Headon, who brought years of experience on the "chicken-in-a-basket" circuit as a pickup drummer for visiting U.S. R&B acts. His weedy looks belied a drummer with the strength and stamina to go the distance with the rest of the band's ferocious sets, and his soulful roots prefigured the band's future musical directions. The lineup of the Clash that would prevail was cast, with Headon the unflagging engine. Manager Bernie Rhodes decided what the band needed for Give 'Em Enough Rope was an experienced producer to smooth out their rough edges. He settled on Sandy Pearlman, Blue Oyster Cult's Seventies svengali. Pearlman and the Clash didn't exactly hit it off, their first encounter resulting in Pearlman's broken nose (a mere "misunderstanding"). Nevertheless, the band and producer encamped in Jamaica for the Rope sessions, the end results a far cry from The Clash.

Though not exactly Blue Oyster Cult's dark, foreboding mix, Rope was definitely more glossy and FM-friendly -- hence its American release before the band's actual debut album. The songwriting, however, had taken a different dimension. "Safe European Home," "English Civil War," and "Tommy Gun" all evinced a move away from one-two punk-rock gut-punching toward a more polished, fully realized, straight-ahead rock & roll sound. The band was definitely maturing in its songwriting and political bent, if not always in its behavior.

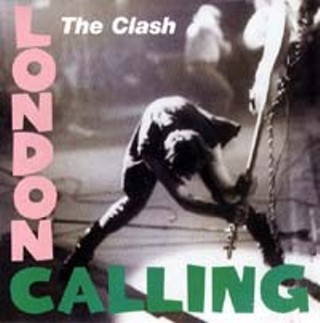

In hindsight, Give 'Em Enough Rope seems like marking time for arguably the band's best effort, 1979's London Calling. Spending time in America for the Rope mixing sessions opened the group up to new ideas and influences that soon crept their way into its musical palette. Teamed with wildman producer Guy Stevens, the band took on rock, soul, reggae, jazz, ska, disco, and R&B grooves, moving even further away from their early roots. The amazing thing is how effortlessly they pull it all off. The cover was an out-of-focus, black-and-white photo of Simonon demolishing a Fender bass in a rage, its layout cleverly echoing Elvis' first UK release. Taking on Elvis was a perfect reflection of the band's reverence for rock itself, but also of their desire to shake it up.

Music critics tend to compare one band to another simply as a convenient (some say lazy) frame of reference for themselves and the reader. In the pages of punk rags over the years, countless bands have been compared to "early Clash," but comparisons to London Calling-era Clash are few and far between. It was a genuinely groundbreaking effort; nothing sounded quite like it before or since.

London Calling was a thinking-man's punk album, even as the band distanced itself from its fast-and-loud punk roots. The 2-LP set took on new thematic directions and fine-tuned its politics even further. There was little in the way of suburban teen angst in the commanding way the band spoke out about the stupidity of war, the corruption of power, and the decadence of throwaway pop culture.

Throughout, Strummer's humor and humanism shine through in the lyrics, such as those in "The Right Profile" and its tale of the star-crossed Montgomery Clift. It was a sort of Sgt. Pepper for the punk years, cinematic images ripe with imagination; compared to what the band's contemporaries were up to at the time, the album still sounds remarkably fresh.

The anthemic title cut has the urgency of an air-raid siren, while "Spanish Bombs" was a romantic look at the Spanish Civil War, with its "trenches full of poets, the ragged armies." Pinter or Kafka couldn't have visualized a more thorough expression of workaday loneliness and alienation than "Lost in the Supermarket," but "The Guns of Brixton" is a call to arms plain and simple, its dark melody set to a West Indian chukka-chukka beat. "Rudie Can't Fail," "Hateful," "Jimmy Jazz" -- there's hardly a bad song in the batch. "Clampdown" was already becoming ubiquitous on FM radio.

Stevens' efforts at flogging the band in the studio came through in the abandon of many of the songs and the LP's blessedly unfussy mix. Added at the last second was one of the great lost-love songs, "Train in Vain," which became a minor radio hit and still endures as a radio staple; its inclusion was so hasty, it didn't even make the album's track listings. Much to Columbia Legacy's credit, the LP's original lyric sheet has been restored and album art, such as the back inset picture at the Armadillo World Headquarters, captioned and credited. Better yet, the sound quality definitely beats listening to a gouged vinyl LP on a cheapjack stereo stacked with empty Schaefer tallboys.

The following year, 1980, saw the release of Sandinista!, the band's sprawling, triple-album epic. Hard-core fans are still split into two camps on the album's merits. One faction insists Sandinista! is the band's masterwork, showcasing its musical breadth and versatility; the other maintains that it would have made an excellent double or even single album, but ultimately contains too much self-indulgent filler (see accompanying feature). Regardless of personal opinion, one fact remains: The album nearly bankrupted the band. Despite objections, the Clash insisted on marketing the album at the same price as a single LP as a nod to its fans; unfortunately, the only way for that to work was for them to waive performance royalties.

That decision, along with touring costs, was bleeding the band dry. Overblown or not, Sandinista! does contain excellent material. The band was picking up whatever instruments happened to be lying around in the studio and picking them, beating on them, or blowing into them in songs that encompassed reggae, dub, punk, rockabilly, jazz, gospel, and disco influences. Standouts like "Police on My Back," "Somebody Got Murdered," "The Call Up," and "Charlie Don't Surf" are fine, anthemic songs in the classic Clash mold. Of course, the wonders of digital technology has allowed the original three-LP set to be condensed to two CDs, much to the consumer's benefit. The reissue also contains a scaled-down reprint of the original's hard-to-read booklet.

At this point, the energy coursing in the band was beginning to spin out of control. Headon was well on his way to a heroin habit, while Jones' ego was becoming a problem as well. Jones could be a very unreasonable and stubborn prima donna, often acting, as Strummer puts it, "like Elizabeth Taylor in a filthy mood." Even amid the turmoil, however, the band's fortunes continued to rise.

1982 brought the American release of Combat Rock. Though considered a mediocre effort by many fans, it nonetheless reached No. 7 in America and yielded two enormous hits, "Rock the Casbah" and "Should I Stay or Should I Go." Despite the sneers of the hard-core fans, songs like "Know Your Rights" and "Straight to Hell" are still eminently compelling and listenable, even if they pale against most of London Calling or even Give 'Em Enough Rope. Combat Rock broke the band into Middle America's consciousness and got them exposure on then-fledgling MTV; the "Casbah" video, filmed in part at the Armadillo, will naturally appear familiar to old-time Austinites.

The album was also a reflection of the band's divergent musical directions, with Mick Jones more interested in the rap and hip-hop that would later define his post-Clash outfit, Big Audio Dynamite. As it turned out, Combat Rock was also the swan song for the original lineup. By the time of its release, the band had sacked Headon, whose heroin use had completely undermined the band's playing ability even beyond its effect on their personal relations. Old friend Terry Chimes was shanghaied back into the band for a stint opening the Who's farewell tour. Chimes, in turn, was replaced by Pete Howard within a year.

Jones and Strummer's relationship was rapidly becoming all but intolerable by this point, culminating in Jones being asked to leave the band in early 1983. He took half of the Clash's driving force with him, and the band quickly disintegrated. Simonon and Strummer soldiered on for another two years, dragooning guitarists Nick Sheppard and Vince White into the band, but the game was clearly up. There's no clearer indication than Cut the Crap, the 1985 effort all involved have disowned and CBS has mercifully opted not to rerelease.

It was over. The Clash had come to the end of their run. They had enjoyed a blinding six-year arc of enduring songs, revved-up live performances, and eventual monetary success that established them as one of the greatest rock bands of the past 30 years. That's "rock band," not "punk rock band." The Clash were punk rock to the very end, eluding being pigeonholed so easily, because their musical plate was far too full to accommodate such a confining term.

Don Letts' documentary Westway to the World makes clear the debt the Clash owes to ancestors the Who, Kinks, and Rolling Stones. Jones in particular never made any bones about idolizing Pete Townshend, Mick Jagger, and Keith Richards, unlike other '77-era punks, who saw them as boring old farts. Marred only by a rather fannish tone, Westway is an absorbing look at the band in their own context and time. Most revealing, though, is the electrifying live footage from over the years, with Strummer speed-tweaky and edgy, Jones ever the rock & roll axeman, and the rhythm section solid as a '65 Cadillac. The footage is as raw and exciting as the grainy film of Elvis twitching his leg on that flatbed trailer back in '55 or Townshend wrecking his guitar on The Smothers Brothers Show, and makes one heartbroken for not having seen the band in its day.

Columbia Legacy has been extremely conscientious with its reissues over the past five or so years, revamping such landmark efforts as Willie Nelson's Stardust, Johnny Cash's Live at Folsom Prison, the Byrds' Sweetheart of the Rodeo, and an ongoing campaign to rerelease the entire Miles Davis catalog. The care and thought put into packaging the Clash material alone is a far cry from the early Eighties, when CDs were stamped out with little more than a folded sheet for art and nothing in the way of liner notes.

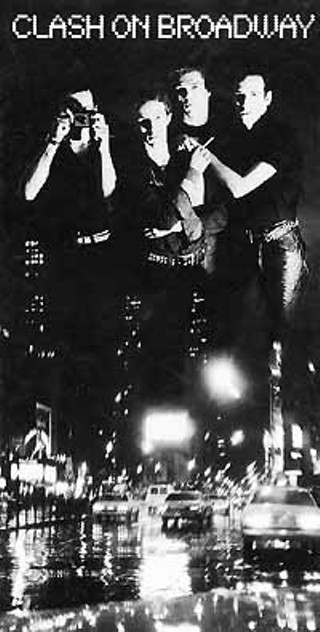

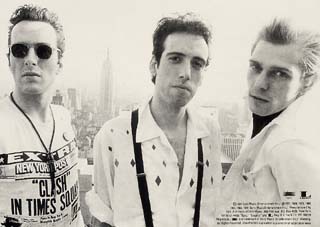

Included in the Clash reissues are The Clash: The Singles collection, Story of the Clash Vol. 1 (with extensive accounts of many a fistfight from ex-roadie Albert Transom), and the excellent Clash on Broadway 3-CD box set for completists. Originally released in 1991, Broadway includes a good deal of previously unreleased material, such as Mick Jones' priceless take on the Small Faces' ballad, "Every Little Bit Hurts," live recordings, and alternate takes. The set also features a fat booklet packed with inside-story quotes from the band, a discography, and an excerpt from Lester Bangs' Psychotic Reactions and Carburetor Dung. A separate booklet contains lyrics, a welcome inclusion for those who have struggled with Strummer & Jones' Andy-Capp diction for a generation.

Also included in the rerelease barrage is the live document From Here to Eternity Live. Sampling gigs from throughout the group's run, the disc gives some inkling of the blistering, fearless energy the Clash could muster up in concert. Catching the band in their late-Seventies/early-Eighties prime, Eternity pulls together live versions of material from the first four albums, and even a couple from Combat Rock. Plenty of fans will grouse and kvell about tracks that could have been put onto this release, but at that rate, this disc could easily have been expanded into two or three. At any rate, it shows the London punk torchbearers as a furious live band, from the scathing "Complete Control" all the way to Combat Rock's "Straight to Hell."

The Clash broke up before they had a chance to become bloated, tired, creatively bereft rock stars. By the time they sat in the envied catbird seat every struggling band dreams of, the end was already in sight. At the time, many rightly noted that it's difficult to stay in touch with working-class rage and angst while being shuttled around in limousines and plied with piles of cocaine and groupie delights backstage in giant arenas. By the time of his exit, Jones had long since been seduced by such rock & roll decadence.

None of the Clash principals have ever come close to the spark they enjoyed in their salad days, but it doesn't really matter. The band was always a perfect case of the whole being greater than the sum of its parts. Any doubts are easily quelled by Joe Strummer & the Mescaleros' Rock Art and the X-Ray Style, a dismayingly flaccid and unfocused amalgam of world beat, electronic beeping and booping, and abstract, if heartfelt, lyrics that came out last year.

The movement the Clash helped ignite has become assimilated into mainstream rock culture, as they opened doors for armies of bands to come afterward. At a time when Buzzcocks songs are used to shill SUVs in TV commercials and kids with spiky mohawks don't elicit so much as a raised eyebrow from adults, it's high time a band like the Clash was seriously re-examined.

While contemporaries like the Damned and the Sex Pistols reunite and trundle their worn-out rock shows around the country for kids who weren't even born when their first albums bowed, the Clash (as of this writing) has grown old gracefully -- and separately. Considering the comatose state of rock in the year 2000, this would be a good time for the band's original fans to snatch up these CDs and force their teenage progeny to listen to them over and over and over again until, at long last, they get it. ![]()