Stories That Tell Themselves

The Texas Documentary Tour: Meet Albert Maysles

By Anne S. Lewis, Fri., Feb. 11, 2000

Albert Maysles is one of the kahunas of cinéma vérité -- or, as he prefers, "direct cinema" -- documentary making. In 45 years behind the camera, he has made over 20 films, along with his brother David (until his death in 1987), including Salesman (1969), about a door-to-door Bible salesman (selected by the Library of Congress in 1992 as one of the 25 best American films ever made), Gimme Shelter (1970), about the violent turn of a Rolling Stones concert at Altamont Speedway, and Grey Gardens (1975), about Edith Bouvier Beale and Edith B. Beale Jr., former socialite mother-and-daughter cousins of Jackie O, who lived contentedly in flea-infested decrepitude in the Hamptons. A former psychologist whose camerawork has been hailed, and utilized, by no less than Jean-Luc Godard, Maysles is still making films at 73. And still waxing reverential about the truths that reveal themselves without any prompting whatsoever, stories that simply tell themselves, in front of a hand-held camera and cable-free sound recorder -- the technology he pioneered in the Sixties and which revolutionized documentary making. He's still unapologetically convinced that subjectivity and point of view have no place in a documentary. Don't even ask what he thinks about seemingly indispensable documentary tools like the interview or voiceover. Maysles has little use for the gotcha!, the in-the-subject's-face style of a Michael Moore, or the blur-the-line-between-fact-and fiction techniques of an Errol Morris. For Maysles, even fellow cinéma vérité heavy Frederick Wiseman puts too much of himself into his films -- he hasn't been able to watch a Wiseman film since that first, reputation-making The Titicut Follies (1967) because of all "that point of view," although he'll allow that Wiseman's style may have matured over the years. Just let that sink in for a moment.

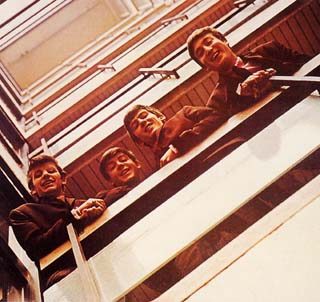

Maysles is bringing two of his early films to the Alamo Drafthouse this Wednesday, February 16, as part of the Austin Film Society's ongoing Texas Documentary Tour: What's Happening! The Beatles in the USA (1964), a "fly-on-the-wall-with-a-hand-held-camera's look at the Fab Four's first American tour" (and a foreshadowing of colleague D.A. Pennebaker's Dylan treatment in Don't Look Back), and Meet Marlon Brando (1965), the Maysles Brothers' riff on a Brando riff with the press during a film promotion. Outside of a retrospective last year, the Alamo screening of the Beatles' film will be its first-ever showing in the theatre, due to a long series of complications. Says Maysles, "When I saw the film for the first time on the big screen last year, I was on the edge of my seat the entire time -- so happy -- every single moment was just right, just right, just right! No greater pleasure for a filmmaker than 30 years later to look at something and see that it has held up."

Maysles concedes that both films are conceptual paradoxes for his style of filmmaking. The Brando film is, of all things, about Brando giving interviews. And in What's Happening!, the Beatles turned out to be merciless hams in front of the camera -- anathema to a direct cinema filmmaker. "We could have told them to stop acting for the camera," Maysles recalls, "but they came to this country having been groomed to act for the camera; that was who they were at that point. We didn't want to shake them out of that. But there were some quite insightful moments that we caught, like Paul on the train, admitting that he was depressed and that the group was being turned into a product."

Austin Chronicle: Is your subject's awareness of the camera a problem for your style of filmmaking?

Albert Maysles: This comes up all the time. People always say that the subjects wouldn't be that way without the camera. But I say, "You mean to tell me that with a camera, all of a sudden somebody is an actor?" In film schools today, the students are being taught all the wrong things. They're scared to death about not being objective enough because the camera is there; then they're scared to death that they're not being subjective enough.

In Grey Gardens, I'm confident that we captured the real Beales. The proof of that is that when the mother was on her deathbed, a year after the film, her daughter asked her what more she had to say, and she said, "Nothing, it was all in the film." Also, every morning during the six-week shoot, we would arrive a little earlier than we said we would so that we could spray ourselves with Off! to keep the fleas off when we were in the house. We'd do this standing just outside the house, so they couldn't see us, and we could always overhear the two women talking to each other. And it was exactly the same way they talked when the camera was running.

AC: Do you interact at all with your subjects when you're filming?

AM: We never ask questions. For example, in Grey Gardens, if we said anything, it was nondirective, as in that kind of therapy where the patient does all the work. If we spoke to them it was just to reflect back what they were saying, to reinforce the likelihood that they knew we were paying attention. We tell our subjects when we discuss the prospective project that we would like to be with them and will be shooting whatever seems interesting. We tell them, if you want to talk to us, please do.

In Gimme Shelter, we were in Mick [Jagger]'s dressing room at the start of the shoot and he came over to us and said, "You know, I'm not going to be an actor in this film." We said, "Well, it's a documentary so we're not expecting you to do that." So then he said, "None of that Pennebaker shit." So I understood that to mean that this film was not going to be our kind of pure documentary. We could have just said goodbye and left at that point, but what we did was just wait, thinking we might get his cooperation. We started filming, and we never had a problem, somehow he just understood what we do.

AC: Your skills as a cameraman have been widely acclaimed. How do you describe your style behind the camera?

AM: My style is very natural, more like a good still photographer than a cinematographer. The cinematographer's job is to set the lighting; he may not even look through the camera. A good documentary camera person is subject to the whims of reality and has to be adept at any moment, like a still photographer, being ever watchful and listening very carefully so he doesn't have to ask someone to repeat something. I never have to say, "That was really great. Now, could you repeat that for the camera?" A good cameraman knows how to use a camera and at the same time be ever watchful. He knows what to shoot and how to give his subjects the love that allows that magical combination of full truth and full subjectivity. The cameraman has to have what I call "the gaze" -- empathy -- the way you look at the people you're shooting and how you establish their trust. Paying attention to people is an extremely powerful force of recognition and of love. And that's documentary at its best. Without their trust, you're just a walking zombie with a camera and your subjects don't connect.

AC: Why were you so pleased with your camerawork in the Beatles film?

AM: My shooting was so good in that film. I was on the right person at the right time. I framed everything right, I was close up at the right time. The shooting was fluid. The shooting of that film was a complete revolution in filming technique -- no one had ever shot a film that way before. The British press said it was a total revolution. We just tagged along with the Beatles; they didn't have to position themselves for us because the camera was no longer on a tripod as it always had been up to then. That meant the Beatles could just feel free to move around and be themselves. That new technology gave us the flexibility to catch a life as it was -- without imposing on people. You didn't have to interview them, heighten the film with music, just real, straight, direct life experiences -- a nonfiction filmmaker's dream.

You have the greatest force behind you when you're filming reality -- if you just let it happen. But a lot of documentary makers force themselves into a mold to capture their own preconceptions, in other words as far away from fact as a fiction film. Errol Morris, for example, there are times when I feel he delights in confusing fact and fiction. I think you owe the public the courtesy of saying, "This is no longer a documentary. A documentary has to be factually correct, none of this hocus pocus, blending fact with fiction."

AC: Are you saying that "direct cinema" is the only legitimate form of documentary?

AM: Well, there are nature films that are probably factually correct. Those are not direct cinema, but that could still be called documentary. A documentary is fact in film. A good documentary is not just hanging a camera on the wall -- there has to be a brain behind it. The brain calls attention to what's important.

AC: Isn't that the dreaded point of view?

AM: You could call it that, but if the POV is set up to give you a message -- the hell with the facts -- that's where POV gets into trouble. When you're getting into "purposes," then you're getting into POV. If your purpose is just to reveal the human condition, then that's okay.

AC: How do you ever purge a documentary of subjectivity or POV?

AM: Well, Grey Gardens was not a POV film, I would say, because we were fair to both the mother and the daughter. We had enough of each of them in the film for the viewer to understand both of them. I suppose you could call being fair to everyone in the film a form of POV. But if we'd tried to make the mother look better or worse than the daughter that would have been the bad POV.

Grey Gardens got ferociously negative reviews, by the way. Walter Goodman at The New York Times said that the Maysles Brothers should be disgusted with themselves for having made that film and taken advantage of those two women. No matter how good a film you make, you have to go through the perceptive process of the audience, and there are some people in the audience who just don't get it. You give them a wonderful gift, and they throw it away.

AC: How do you see narrative in a documentary?

AM: That's a very delicate thing. Sometimes you end up with a film that has no narrative and have to decide, well, maybe that's the way to show it.

AC: Do you edit your own films?

AM: No, I don't really take part in the editing, which may seem funny. My brother always supervised the editing and would give a lot of freedom to the editors. That works, both by virtue of the person we select to do the job and by the nature of what we've got to begin with. So far, our editors have, with the exception of the Christo project, produced the story that we wanted.

AC: So what's next?

AM: I'm off to Florida to do some filming of Edie Beale (the daughter in Grey Gardens) who's now living in Miami. She's now the age her mother was in the film and doing great. I'm also working on an ongoing project about meeting strangers on trains. And working on a profile of Mendel Beilis. I also do a lot of seminars.

I have an office of eight to 10 people and some of them are working on commercials and infomercials. ![]()

What's Happening! The Beatles in the USA and Meet Marlon Brando will be presented as part of the Texas Documentary Tour on Wednesday, February 16, 7pm & 9:30pm, at the Alamo Drafthouse, 409 Colorado. Filmmaker Albert Maysles will be in attendance to introduce each film and conduct a Q&A session afterward. Tickets are on sale by phone (322-0145) through Tuesday (10am-2pm) for AFS and KLRU members only. Tickets will go on sale at 6:15pm on the day of the show. Admission prices are $6 per show for the general public; $4 for Austin Film Society and KLRU members and students. The Texas Documentary Tour is a co-presentation of the Austin Film Society, the University of Texas RTF Dept., The Austin Chronicle, KLRU-TV, and SXSW Film.