Bright Lights, Inner City

When Austin's Eastside music scene was lit up like Broadway

By Margaret Moser, Fri., July 4, 2003

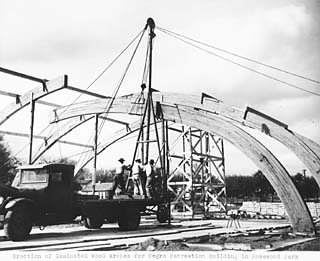

(Austin History Center pica 25180)

"The Cotton Club was down on 11th Street, just off I-35, coming east right before you get to Ebenezer Baptist Church, at San Marcos Street," remembers Ernie Mae Miller. "They had nice bands there -- Duke Ellington, Count Basie. It must have been the Forties when it got torn down, when I was a kid. Right next door was the Paradise Inn. They had a jukebox, but every now and then, they'd bring in a band.

"My mama would tell me, 'Now, y'all go to BYPU,' the Baptist young people's group, 6 o'clock Sundays. So we'd go into Ebenezer, then out the back door and down to the Paradise. My mama came by there with a switch one time, switched me all the way back home. I just wanted to hear the music!"

And it was the music that shaped Ernie Mae Miller's life. The 76-year-old native was a band student at L.C. Anderson High School, Austin's black high school of the day, which was named for Miller's uncle. Back then, she was known by her maiden name, Crafton, and she played baritone sax. At Prairie View College, she joined an all-girl big-band revue known as the Prairie View Co-Eds, who traveled the country playing army bases, camps, and USOs, even hitting hot spots in New York City.

Afterward, Miller returned to Austin, traded the baritone sax for piano, and by the Fifties, had established herself as a solo musician and singer -- in part because her husband didn't care for her touring with male musicians. Miller crossed racial lines early, playing clubs patronized by whites such as Dinty Moore's, and in more recent years, she played nearly every hotel bar in town.

Miller's most famous gig ended its 16-year run in 1967 at the New Orleans Club on Red River Street, then considered the western end of the Eastside's 11th Street entertainment district. Popular music in the Sixties underwent the birth of rock & roll, which boosted the audience for its parent genre, rhythm and blues, but the results were not always beneficial to the black community. Nevertheless, traditional musicians such as Miller sometimes found themselves in the most interesting of places with the most interesting of company.

"At the New Orleans Club, I played downstairs, and the 13th Floor Elevators often played upstairs," recalls Miller. "One night it rained, and the place got flooded. That night I'd bought a brand-new pair of red suede shoes. You had to walk down about six steps to get to the club, and that night I had to walk -- slush, slush -- across Coke cases through the water, while upstairs was the Elevators with people dancing.

"I sure did like those shoes."

Rockin' in Rhythm

In a dark, poorly documented corner of Austin's memory, it's pure speculation to suggest that the town's fabled music scene started in the jazz age of the Twenties. It's quite possible, however, that young Duke Ellington loaded into Austin's Cotton Club at the same time that Louis Armstrong was polishing his trumpet in preparation for his well-documented gig at the Driskill Hotel. Jazz was so pervasive at the time that it was being incorporated into country & western music and called Western swing. With the Depression just around the corner, music was as vital to the culture here in Austin as in Harlem or New Orleans.

The presence of active military bases at Bergstrom and Fort Hood (then Camp Hood) meant soldiers on the town every weekend. Documents on and of the time imply that the rowdy atmosphere led to scrutiny by the city and subsequent regulation. By Ernie Mae Miller's recollection, the Cotton Club and Paradise Inn were closed by the end of the Forties.

Meanwhile, Huston-Tillotson College's jazz programs were in full swing, the Apostolic Church at Comal Street and Blackberry offered teen dances, and a place called the Black Cat on 12th was popular, but not until Johnny Holmes opened his Victory Cafe on V-E Day in 1948 did the scene revive. By the time the cafe moved a half-block toward town as the Victory Grill in the Fifties, other clubs like Tony Von's Show Bar -- previously the Black Cat -- were booking live music, too. As Henry "Blues Boy" Hubbard looks back on it, "The Victory Grill was it," but changes were afoot.

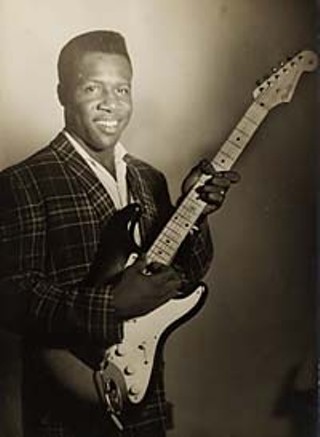

"I was playing piano with a trio at the Victory Grill about 1956," says Hubbard, 69, "when Tony Von had a jazz group at the Show Bar that wasn't drawing so well, and he invited me to get on guitar. We got a group together -- no name, just a group -- and within a week, the house was packed, and no one was at the Victory. I went up to the Grill on a Friday not long after, and it was only the people that worked there sitting around looking at each other."

By the late Fifties, East 11th Street and its jog up 12th was Austin's musical destination, much as Sixth Street is now. "Lit up like Broadway," is how some describe the snaking blocks of clubs that attracted jazz, blues, and R&B players of every caliber. Clubs with names such as the Clock Lounge, Good Daddy's, the Palladium, the Shamrock, Slim's, and Steamboat attracted a lively following. Like Harlem, the scene jumped with lines to get into clubs, flashy cars, and well-dressed patrons of every color out for the weekend stroll. For a young musician like Hubbard, it was heaven.

The military brought Hubbard to Austin, stationed him at Bergstrom AFB, and here he stayed. In addition to the Victory and Show Bar, Hubbard and company played after hours at places such as Cheryl Ann's on Webberville Road, near the outskirts of town. It was a good time to be young and in the swing of things; the unlikely benefit of segregation was the tightly knit black community that thrived in East Austin.

"During the time we played at the Show Bar, Charlie Gildon bought the place," explains Hubbard. "He bought the whole block there -- barber shop, cleaners, liquor store, shine parlor, and the club. And when he bought the place in 1958, he called me and said, 'I got part of your band, and they want to make you the bandleader.' Charlie and his wife wanted it to be a business and wanted a name for the band. So I said, 'Why not the Jets? I'm a jet mechanic at Bergstrom.' And that's how it came about."

Dance to the Music

Pay attention when Allen "Sugar Bear" Black emcees at Antone's. He's been a fixture at the club since the Seventies; he walked into its original location at Sixth and Brazos Street with former Show Bar owner Tony Von to promote Johnnie Taylor and stayed for the next three decades. The tall, handsome man may stand at the door of Antone's as a greeter of sorts, but he's a direct link between today's downtown blues scene and the glory days of the Eastside.

(courtesy of Tary Owens/Austin History Center)

"I was a youngster in 1965, going to Charlie's Playhouse," recounts Sugar Bear. "I saw bands like Al 'TNT' Braggs, Tyrone Davis, and Albert Collins, but mostly it was Blues Boy Hubbard and his Jets on the weekends. It was basically a Blue Monday club for blacks, but on Friday and Saturday nights, it was 95% white -- kids from colleges and the University of Texas.

"It was real unusual to have that. They didn't fear coming to the Eastside; people didn't get their cars vandalized, stuff like that. More like it is now, with blacks and whites in clubs together. There'd be a constable out there with a pistol, to keep people from loitering if they weren't coming in."

The presence of a young white audience on the Eastside had been building since the late Fifties. Hubbard theorizes that the proximity of the neighborhood to UT was the crucial link.

"The fraternities wanted somewhere to go every week," he states. "Here's a club on the Eastside that's all black, and it turned all white. I wasn't surprised to see it -- if you'd seen how the kids were going on over that music. ... When we'd kick that first number, they'd be on the dance floor and wouldn't leave. They'd dance when we weren't even playing. They just couldn't get enough of it.

"The blacks on the Eastside would come to Charlie's and get turned away. Not exactly turned away, but no room to sit. The fraternities reserved tables for 20, 40, 50, and the Playhouse was full before we'd even kick off. The white college kids were spending more money than the black kids because they had more money. It got to the point that blacks on the Eastside coming from the projects were getting mad at Charlie because of that. But Charlie was looking out for Charlie."

The impact of a moneyed white audience bolstered East Austin's economy. Hubbard saw the changes from a businessman's point of view as well as an artist's.

"Charlie's brought the white kids from the west side and the runoff enabled the other clubs to have a heck of a business," he explains. "Like Sam's on 12th Street and the IL Club across the corner from Charlie's Playhouse. And when Charlie's was full, the kids just said, 'We'll go to the IL Club,' because he had a band, too. They just tore that club down a year or two ago.

(courtesy of "Blues Boy" Hubbard)

"Sam's Showcase was the only other club to give competition to Charlie's, really. W.C. Clark was playing with me then and would say, 'Well, Charlie's paying $10 a night, but Sam is paying $12.' So he'd end up going to Sam's and play with Major Burkes for a while.

"So Sam and Charlie got together on what they wanted to pay the bands. Sometimes, the musicians would get tired of the same crowd and jump the fence to play another club. The grass always seemed greener. But next thing you know, they were back with me. Until 1970, Charlie had one heck of a business."

Charles Ernest Gildon, "or maybe it was Ernest Charles Gildon, I'm not sure," was Sugar Bear's uncle, a man with a glad eye for a dollar who was in the right place at the right time. In 1960 he bought the after-hours joint called Cheryl Ann's and renamed it Ernie's Chicken Shack and would often continue the night's music from the Playhouse into the morning's wee hours. Hubbard's Jets became the after-hours band at Ernie's, a gig that made them local legends.

Mississippi-born Lavelle White was already a veteran musician based in Houston when bookings brought her to Austin in the Sixties.

"I came to Austin to play," she says, "and I played a gob of clubs: Charlie's Playhouse, the Derby, Good Daddy's, Sam's Showcase, the Victory Grill. Joe Valentine had a club, too. There were a lot of clubs there and really in the swing, you know? They were really doing it.

"Ernie's Chicken Shack -- that was a rockin' place, and I was a rockin' girl. That place was so jumpin', and the best food -- mmm, mmmh -- you ever ate in your life! That fried chicken and fish was just mouth-watering. It was really hoppin', I'm telling you.

"Everybody went there, every weekend night. You could hardly find a place to sit. Dancing and music. Gambling going on in the back room, yes there was. They had bootleg liquor and Blues Boy Hubbard & the Jets. It was wonderful."

Sign of the Times

As quickly as it came, the scene went. By the early Seventies, the Victory Grill had closed, as had Charlie's, Sam's Showcase, and the IL Club. Ernie's Chicken Shack served its bootleg liquor and hosted the Jets after hours until 1979, when Gildon died. Nearly every one of the musicians interviewed cites the same ironic factor in the decline: integration.

Integration isn't the only reason given; drugs, crime, and the changing times played their part as well. Today, the limestone structure known as Symphony Square stands where the New Orleans Club was located, and to look up the block from there toward I-35 is to see how successfully a bit of architecture can affect a culture. The interstate that quite literally divided the city was, as Harold McMillan says, "symptomatic and not causal."

McMillan moved to Austin in the late Seventies as a student and musician, and his experiences as both led to the founding of his local preservation organizations, DiverseArts and the Blues Family Tree Project.

"Once the desegregation legislation happened," says McMillan, "like the Voting Rights Act, black folks had a false sense of victory. We assumed that when the laws changed, we could go all over Austin and do whatever it is we do -- see music, eat wherever we want. No need to do business just in central East Austin, because investment will come here, too, and it'll be just fine. Instead, especially in businesses and clubs, it started to die off."

Some of this was due to what McMillan calls a lack of "critical mass of African-American political and economic power in Austin because the community is so small." He concedes that the decline happened all over the U.S., yet correctly points out that cities like New Orleans did not turn its back on its musical heritage simply because the times changed.

Like McMillan, Rudy Malveaux came to Austin as a student and would like to see the times changed back. Malveaux also worked as a musician and rapper, playing clubs such as the Mercury, Electric Lounge, and Mercado Caribe. As owner of a small grocery in East Austin in the late Nineties, Malveaux became friendly with a customer named R.V. Adams, who owned the Victory Grill.

In 1997, Malveaux was trying various musical efforts, but the one that took off featured Bobby "Blue" Bland, the Houston R&B singer who'd been a star at the club in the Fifties and Sixties. Opening the show was a local teenage guitarist, Gary Clark Jr., who played with the Blues Specialists and is among the last of the keepers of the Eastside flame.

"When you bring back Bobby Bland, debut Gary Clark, and have an institution like the Blues Specialists, where do you go?" asks a frustrated Malveaux.

(courtesy of Tary Owens)

Malveaux's question is one he's pondered for six years. In that time, he's worked with Showtime, the Austin Music Network, and a variety of musical acts and events at the Victory Grill, including the Juneteenth MusicFest two weeks ago. Not all his efforts are profitable, but his spirit is unflagging, because he believes now, as then, that "the Victory Grill is the cultural hub of East Austin."

For veteran musicians like Lavelle White, the memory of the Victory Grill in its heyday clashes with today's reality. She bluntly states there's no place in Austin for her to play any longer and talks of moving away after her new album is released this summer.

"If you're a skinny white boy with a guitar, you got a gig," she asserts. "But no one wants to see a black woman with talent."

Without rancor, Blues Boy Hubbard agrees.

"Lavelle is right," he says. "I was lucky back then; I got with Charlie, and Charlie's living was me. He hired me in '58, and I played for him 'til he died in '79. Every week. But the other black musicians didn't have a place to hang their hat for 10 years. The club owners kept coming and going. Get a band to a club for a year, someone else buys the club, maybe he don't want a band.

"Then I went to the Austex and the Continental Club, the Opera House, Steamboat. I met Steve Dean, Clifford Antone, Chuck Geist from Hut's, C-Boy, and Hank Vick, and these guys all kept me working, opening for Bobby Bland, John Lee Hooker, the Fabulous Thunderbirds. I played the Guadalupe club for a month one time, playing to a lot of college kids, just like the old days at Charlie's Playhouse."

There's an arch over the entrance to 11th Street from I-35 today, and it's a bellwether of new hopes and old dreams. Drive up 11th Street and the revitalization is evident in refurbished buildings, construction, and a cleaner look to the area. Everyone agrees it's a positive step for the neglected community: Build it, and maybe the people will come.

Yet the frustration in Lavelle White's voice is understandable. In her mind, the Eastside's musicians are still relevant and should have a place in the music scene on both sides of the interstate: "It's time to make people wake up and smell the music. That's my new saying: Wake up and smell the music." ![]()