A Lot of Cojones and a Little Faith

The art of Micael Priest

By Margaret Moser, Fri., Oct. 6, 2006

On Thursday afternoon, two days before the opening of Micael Priest's exhibit at the South Austin Museum of Popular Culture, there was no poster for the show. This isn't a surprise to anyone who knows Priest, a child-prodigy cartoonist who won a scholarship to California's Disney art school in seventh grade but moved to Texas before he was able to use it. That award-winning style, bold and distinctive even then, later defined the look of the famous Armadillo World Headquarters posters in the Seventies.

"I've been a resident of Austin since 1969 who was deeply involved with imaging Austin's burgeoning music industry in the Seventies and continues to influence the look of Texas film, video, and advertising," he states with little modesty and a lot of truth.

To many, Priest rules as the godfather of poster art in Austin because his work is among the most enduring. Jim Franklin had created the armadillo as the symbol of the hippie counterculture in Texas, but Priest, with his cartoonist's sensibility, used black ink to fill their veins with red blood. His anthropomorphic 'dillos didn't simply jump around, they danced, flirted, talked, gossiped, drank beer, smoked pot, and celebrated life.

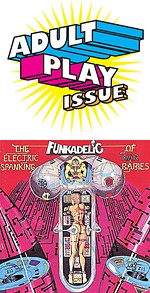

Taking the signature animal of AWHQ and putting his own autograph on it led to a successful but not necessarily lucrative career designing logos, CD covers, ads, games, and more. Priest not only was witness to the cultural revolution as it took place in Texas, he participated in it, illustrated it, and stuck around to see his art become history. Just about anything that needed original art in this town, Micael Priest has drawn.

"I have always been enamored of Disneyesque," he reflects. "Which was actually a brush style where you used the varying thickness of line to imply weight, depth, or shadow."

"That's something I learned from [Jim] Franklin. I had always been a cartoonist, symbolizing things instead of depicting them. Franklin showed me you could sculpt by drawing fields of tone with crosshatches. I was way into the idea of depth and was way into outlining with variable thickness lines like Al Capp's Li'l Abner or Walt Kelley's Pogo, but he showed me how to make it look like you were reaching into the drawing. The tendency is to do a smooth fade by using a pencil because you do it by letting up on the pressure and going lighter. Franklin broke the code about doing that with black ink on white paper. He learned it from Doré and all those old guys, of course, but he brought it to us."

In person, Priest seems to be related to Samwise Gamgee, but really he is the charter president of Austin's Lost Boys. That's the gang of artists – Armadillo and otherwise – who populated his Sheauxnough (say it like "sho' nuff") Studios in the late Seventies and early Eighties. It wasn't his first time at the rodeo, corralling like-minded art sensibilities, but the epiphany was striking.

"We worked together. I can't stress enough how important this was for us. I was able by dint of the fact that I was director of Directions Art Company and then Armadillo to assemble an incredible team of graphicists and do away with the bad aspects of competition. Any technology or tricks we knew, we shared, in a big room where we could all sit together. If one person learned a new trick, within a month, everybody knew it. It didn't matter if you needed it at the time. If you tripped over that same log later, you said, 'Oh! I know how to do this!' Or if you got stuck, you said, 'Hey guys, come over here.' The most important thing about what we did was, all of us together could masquerade as adults, but in fact we were just kids. We had a club. It was our college, our church."

Priest's speaking voice sounds a good bit like character actor Wilfred Brimley's, which is why talking with him about art is a little like going fishing with your grandfather. Yes, you may catch a fish, but more likely, you'll leave with a head full of stories about the way things were. His replies often turn into anecdotes wrapped in a bundle of loosely related events and details, such as this explanation on how hippies made Shiner beer famous:

"Joe Gracey brought Shiner to Austin one case at a time, only it was Shiner Premium at the time, which was orange because in 1966, Cosmo Spoetzl decided college kids wouldn't drink dark beer, so he put corn in the mix, which made it taste funny, and every batch was different because it had no preservative in it. This doesn't have anything to do with the poster show, but it does have to do with why we were like we were then."

The Shiner tangent seems a long way from "tracing girls out of comic books and leaving off their clothes." His mother Doris showed a strong artistic streak inherited from her father, who was an artist, too. The cultural icons of the day had a lasting effect, as did religion. "I'd been a fan of MAD Magazine, but we weren't allowed to have that sort of stuff, being Church of Christ and all. And we certainly weren't allowed to have the Mars Attacks bubblegum cards."

It's also a long way today from the days when posters plastered Austin street-corner telephone poles and the sides of buildings. In 1972, Priest organized the local artists, who set the going rate of $70 for a poster, a time when rents averaged $100 a month. And in the Eighties, posters (like videos) stopped being promotional devices and became merchandise. Along with the cost-of-living hike came a new generation of artists. Competition wasn't the enemy, however. The enemy was time.

Nothing illustrates that better than the suicide of artist Jack Jackson last June. At the memorial service, Priest wept publicly to the hundreds of mourners while demonstrating the cramped way Jack's diseased-wracked hand held a pen. Yet it's fair to say that some of the tears were for his own future.

Micael Priest, who has always been nearsighted and color-blind, subsists on disability payments between the occasional job. His portfolio cabinet lives at the house of one friend while he rents out the garage of another and uses the phone of a third. He's got two kinds of ADD – the real thing, plus arthritis, diabetes, and depression. It's an almost bitter footnote in the history of a town that knows no bounds in providing mental and physical health programs for musicians but nothing for those who keep the musicians working. It's even more ironic for someone who created lifetime images for 75-minute sets that ended decades ago.

Priest is circumspect about the situation. Some things change, some things don't, and time goose-steps on, whistling the "Colonel Bogey March." One saving grace is those who continue the poster tradition.

"I've never met him, but I love [Chronicle illustrator] Doug Potter. When I do meet him, I'm going to pick him up and carry him 'round and 'round, because he does that wonderful line quality I love so much. I had a lot of hope for Martian [aka Paul Sessums], but he couldn't get over trying to be the baddest motherfucker in the valley. And I love Billy Perkins, because he's kept the kid in the picture."

By 7:09pm on a late September Saturday evening, a poster for the museum show had appeared. Hundreds of old friends and new fans wandered around the exhibit, remembering events they'd attended, ruminating on those they hadn't, and getting an eyeful of Priest's life's work. An earlier rain left clean night air, cooled by a light cold front. Outside, a band pumped out Eighties and Nineties favorites, and God's own light show flashed in the distant sky.

Micael Priest stood in the asphalt parking lot, beamed over the proceedings, and disappeared into the crowd. ![]()

"Micael Priest: Naked Under His Clothes" runs through Oct. 29 at the South Austin Museum of Popular Culture, 1516 S. Lamar. Priest gives a studio talk on Sunday, Oct. 15, and celebrates his 55th birthday on Saturday, Oct. 21. For more information, call 440-8318, or visit www.samopc.org.