Renegade

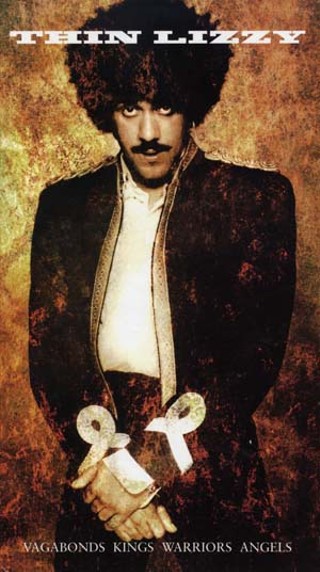

Thin Lizzy's Phil Lynott, 20 years dead

By Raoul Hernandez, Fri., Jan. 20, 2006

"He's just a boy, that has lost his way. He's just a boy, that's all." – "Renegade," 1981

Angel of Death

The song blinks online suddenly, with a dread, electronic tremor, displaced air rumbling like a blackened storm front. From the quickly gathered gloom rises a thick, futuristic wail, air-raid warning for alien skies.

"Oh my God," groans a voice, horror dawning. "There's millions of them."

(The egg chamber?) Up sounds the siren once again, this time trailing off into abandon before the synthesizer slithers down from its red laser lighthouse and into the animal hold. A drummer sets off across his cymbals, and out of this dark apocalypse bursts a galloping bass, thundering into the foreground, guitars snapping at its flank.

"I seen the fires start in 'Frisco, the day that the earth quaked," calls down the prophet baritone, Hendrix hewn, Presley hung. "I seen buildings a-blazing, blowing up in flames. I heard men, women, and children crying out, to their God for mercy. But their God didn't listen, so they were burned alive!

"They went down, down – deep underground. A real disaster."

I sat up, staring at the angry digits on the now rattling clock radio.

"I was hanging out in Ber-lin, in the year one thousand nine hundred and thirty-nine. I seen Hit-ler's stormtroopers, march right across the Maginot Line. I seen two world waaarrrs," he snarls. "I seen men send rockets out into space. I foresee a holocaust, an angel of death, descending to destroy the human race.

"Down, down, deep underground. A real disaster."

The blitzkrieg rages until a Les Paul cuts through the din like a saber from the Napoleonic Wars. Smoke and sulfur clear, momentarily, Brian Downey appearing once again on the edge of his Zildjians (or the like), Darren Wharton whirling up synthesized sorcery. The Supreme Being, vox digitally fogged, rustles a page from the manuscript of time, slowly, deliberately, finger pointed in accusation.

"In the 16th Century... there was a French philosopher by the name of Nostradamus, who prophesized that in the late 20th Century, an angel of death [cue the saber], shall waste this land. A holocaust, the likes of which this planet has never seen!

"Now I ask you. Do you believe this ... to be ... true?"

Last verse and chapter: "I was standing by the bedside, the night that my father died. He was crying out in pain. To his God he said, 'Have mercy, mercy!' His body was riddled with a disease, unknown to man so he expected no cure. But before he died that night, he was lost – insaaane.

"He went down, down, deep underground. A real disaster."

A quarter century later, as "Angel of Death" flickers back down into cyber sleep, synthesizer snaking away with a final buzz, Phil Lynott steps out from behind the curtain at song's fade, a sheepish grin on his swashbuckler's mug.

"I think they've gone now."

Renegade

Whatever gremlins the singer saw that night, death came for Phil Lynott (Lih-nit) on January 4, 1986, and if he wasn't crying out in pain, to his God for mercy, mercy, it was only because he was already lost. His body was riddled not with AIDS, but another epidemic, hepatitis, and internal abscesses from years of heroin addiction. Staph infection, pneumonia, a broken band/marriage/heart, take your pick. All were pallbearers at the funeral of the 36-year-old father of two.

I was in college then. The news was faint, details unclear. No one seemed to care. Not even me maybe; it was too sad and lonely to contemplate. I hope to hell I played "Renegade" over and over and over again as I still do today.

Opening Renegade like Ebola, "Angel of Death" is an extreme version of Thin Lizzy – less so as the band neared its 1983 demise – but the title track is not. "Renegade" is both quintessential Lizzy and Phil Lynott to the core. His dark coffee murmur tickles your ear, Barry White, one minute, and when the Lizzymobile lurches forward like a den of thieves, Lynott's grizzly bellow leads the way. Jackrabbit beats leap, while the guitars hammer and run, kick and tear. Six minutes that move from Michael Mann to Mad Max, Muhammad Ali to Vanishing Point. Fittingly, Renegade reprints only three verses of lyric to accompany the album credits.

Just a boy... that has lost his way

A rebel... fallen down

A fool... blown away

A Renegade

A clown... that we put down

A man... that doesn't fit

A king... alone

A bike is his throne

When he rides he's like the wind

Check his face... look into his eyes

I wonder why... he cries from inside

He's just a boy within us all

But still he is a stranger

A Renegade

The Renegade committed all his romanticism to parchment with a quill.

"Phil Lynott often saw himself as a poet," acknowledges fellow countryman and loyal acolyte Bob Geldof in DVD documentary Out of Ireland. "I think he was stretching it."

He was, more often than not, but then Lynott's tale – illegitimate black Dubliner turned international idol – could well have sprung out of his songs instead of the reverse.

"The Friendly Ranger at Clontarf Castle," Shades of a Blue Orphanage and "Vagabond of the Western World," "Wild One," "Warriors," "Solider of Fortune," even (lady) "Killer on the Loose." Wandering clans and warring tribes played a far greater role in Lynott's reality than simple ancestry. Every Lizzy song, to one degree or another, is by and about Lynott, and he was seldom at a loss. According to 2004's Thin Lizzy: Soldiers of Fortune, however, one of several well-meaning band bios, Lynott's bottomless moor of inspiration continued to petrify during the Renegade sessions.

"It seemed to go on for ages, nobody could come up with a title for the album," [producer Chris] Tsangarides remembers. "We were in Odyssey studios and Phil had left for a while before he came running back all too soon with an idea for the album. He had seen some kid on a bike with a denim jacket bearing the Lizzy logo but also the word 'Renegade' written down the side of it. That was enough for Phil."

Hollywood (Down on Your Luck)

Lynott's aortic bassline intro to "Hollywood (Down on Your Luck)" and the song's grinding, fat-cat hooks sank like a stone as Renegade's sole single.

"They say people out in Hollywood live their life out in black and white," growls Lynott. "They're living out a Technicolor dream, next day they're a star overnight. Not like in New York – man, it's tougher. Not like in London Town, boy you suffer."

The guitarists echo Lynott's cries with the song's parenthetical chorus.

Nobody give a damn (when you're down on your luck)

Nobody understands (when you're down on your luck)

Lady Chance, she won't dance (when you're down on your luck)

In fact, Lady Chance sat out a number of crucial jigs throughout Thin Lizzy's career, whereas London Town, where Lynott lived and died, suffers fools only too gladly. "The Pressure Will Blow" and "Leave This Town," meanwhile, separating "Renegade" from "Hollywood," jump-n-thump like one of Jim Thompson's pulp fiction gangs beating a hasty getaway. Lynott's crew wasn't so fortunate.

When anemic sales undercut a European tour supporting the band's next album, Thunder and Lightning, the group pulled the proverbial plug after 13 years and the same number of studio LPs. Thirteen's a scream (when you're down on your luck).

That Lizzy never conquered the states after Jailbreak went Top 20 and its eternal flame, "The Boys Are Back in Town," pulled up at No. 12 in 1976 was the nail through Lynott's feet. The song's rousing bravado was initially delayed live when the band cancelled an important leg of the U.S. trek after its frontman contracted hepatitis. When Lynott rebounded later that same year with what many regard as Jailbreak's better half, Johnny the Fox, the American tour was scrapped when guitarist Brian Robertson ripped open his hand on the eve of the campaign.

What audiences missed – and then some – appeared two years later as Live and Dangerous. XM radio's precursor, FM, jumped aboard Lizzy's cover of Bob Seger's tea queen "Rosalie" and tried to hold on for eight seconds as the band bucked and snorted, the lashing solo cutting into the Seventies psyche. "Cowboy Song" burst the chute next on the band's trademark twin lead guitars, riding buffalo from Texas to Mexico like John Wayne and Montgomery Clift, before charging straight into a take-no-prisoners "The Boys Are Back in Town." On the subsequent Live and Dangerous video, Lynott's iconic Afro crown nearly eclipses his Les Paul dyad, flame-throwing Scottsman Robertson and SoCal surf disciple and Lizzy mainstay Scott Gorham.

Last summit Black Rose drew blood next, as did Lynott's go-to guitarist and Belfast bad boy Gary Moore when he fled the hot house midpromotion (replaced briefly by a pre-Ultravox Midge Ure). 1980's Chinatown, a bad destination for voracious appetites, took a wearying Lizzy to North America one last time with the Renegade clique, whose European rampage left a hoofprint on at least one opener.

"I wanna thank Philip Lynott for letting us open the show," announces Bono five anthems into the Go Home: Live From Slane Castle, Ireland DVD, receding 20 years to U2's initial appearance at the hilltop fortification. "We're a band from the north side of Dublin. We're called U2. This is our first single. We hope you like it."

In "Out of Control," ol' Philo no doubt heard the ring of truth.

Fats

Thin Lizzy was no Iron Maiden – no metal act – God love Lynott-adherent Steve Harris, his thoroughbred bass, and his twin guitar troopers nonetheless. Rather 1971's Thin Lizzy sods folk-inflected London blues on its way to the subsequent smash rewrite of trad Irish hoist-up, "Whiskey in the Jar." By 1973 and Vagabonds of the Western World, inked sci-fi by Dubliner Jim Fitzpatrick, the original trio fires up far more experienced, bold as lust. Jimmy James disciple and Lynott's first guitarist in an endless succession, Eric Bell, coined the group's moniker after a robot in English comic Beano, forever read by another famous Londoner on the cover of John Mayall's Blues Breakers With Eric Clapton.

Manifest in Live and Dangerous' roiling "Massacre," for one, is the Temptations' grand "Ball of Confusion," Lizzy's nuclear R&B stretching back well before Vagabonds respite Nightlife and its slick runaway "Showdown." Another Fitzpatrick art prowl, Nightlife bows to B.B. King on its titular regret, while Gary Moore's finest weeper, "Still in Love With You," burns for Van Morrison's stoney bark. 1975's follow-up, Fighting, hatches Lizzy's twin guitar thrust, but the hardscrabble "Spirit Slips Away" battles for every centimeter of rootsy recognition. Ultimately, Lynott's earliest songwriting triumphs distinguish themselves as balladry, like Vagabonds' cocooning flower, "Little Girl in Bloom." The tears Sinéad O'Connor could wring with such a tune.

Heard as a tribute to 17-year-old Philomena Lynott, who left a nest of Catholic siblings in Dublin for post-war London, where she was courted by a tall, dark-skinned Brazilian named Cecil Parris, "Little Girl in Bloom" relates only half the saga. Born in Birmingham, England, birthplace of Black Sabbath and Judas Priest, young Philip quickly shipped out to the Emerald Isle, where he was raised by his maternal grandparents.

On two early B-sides, "Black Boys on the Corner" and "Half Caste," not to mention his debut solo album's Apollo-like shout-out, "Ode to a Black Man," Lynott's racial background gets a good going over. When he laments about "that old hangin' tree" in Fighting's "Freedom Song," you hurt too. In this black light, Jailbreak's Orwellian concept plays out as distant cousin to the otherworldly star wars of Bootsy Collins and George Clinton. Lynott's meaty cameo as Parson Nathaniel in the recently reissued late-Seventies audio production of War of the Worlds out-hams narrator Richard Burton.

Renegade's soul quotient cuts the album's heavy atmosphere with Lynott's inherent playfulness, in this case the 1920s jazz razzmatazz of finger-snapping gigolo "Fats," who inhabits the world of cats and chicks, Derby hats and spats, lipstick matching the carnation on his tux. Speakeasy humor aside ("Well Sigmund Freud, he gets very annoyed"), there's no reason not to believe the ditty a heartfelt ode to jazz trumpet titan Fats Navarro. Ensuing tumble "Mexican Blood," flamenco flourish and castanets like cantina crickets, drums up a roguish dime store drama up near El Paso in three easy characterizations:

"She was a Mexican girl, she had Mexican blood. I seen it the night that she died."

"He was Mexican boy, with a Mexican smile, and he drank a little tequila!"

"He was a cowboy's boy, and a cowboy's son ... he was the law."

Duel in the Sun, starring Phil Lynott.

It's Getting Dangerous

"The man finds himself alone for the first time in his life. He knows he's got a problem, got to work it out wrong or right."

Renegade ends as it begins, Lynott contemplating his fate as good and evil wage World War III. "Shades of a Blue Orphanage," on which its nearly orphaned author remembers the Dublin movie house "where me and Hopalong and Roy Rogers got drunk," had long since turned toward Nightlife's junkie prayer, "Dear Heart." Trace the "Opium Trail," starting on 1977's Bad Reputation, and the further pleas for help on its closer "Dear Lord," through to Black Rose's "Got to Give it Up," Chinatown's "Sugar Blues," Renegade sweeper "It's Getting Dangerous," and "Bad Habits" from Thunder and Lightning.

"Now who in the world would believe he's got another trick up his sleeve? And who in the world wants to know which way he should go? Which way should he turn? Which way should he learn? Which day should he stop? Which way to the top?"

Thin Lizzy had one last ace up its Scully shirt sleeve, flaxen-haired gunner John Sykes, whose "Cold Sweat" on Thunder and Lightning serves as the group's raw hide swan song. A cramped quarters guest spot on Irish TV, 1983, crowds a bloated Lynott bashing out the song in the group's closing incarnation, and even then the singer's roguish winks at the camera betray his omnipresence. More than 20 years later, in Selma, Texas, Sykes and Scott Gorham nailed "Cold Sweat" as Thin Lizzy 2004 at the Verizon Wireless Amphitheater. Restoring rock royalties like "Waiting for an Alibi," "Are You Ready," and "Suicide" to the public realm can't be a fruitless endeavor.

Sykes and Gorham's snaking uni-lead, fused to Lynott's taut bassline and Brian Downey's funk beat, divine Thunder and Lightning's centerpiece, "Holy War," another chapter torn from Nostradamus. When Lynott's theological dialog parts briefly on Lizzy encore Life-Live, "Holy War" pounds the pulpit.

"Just as Satan, tempted Jesus," hisses Lynott, "and Jesus, slips and falls. He's a station, on the cross now. He has died to save us all.

"Then lead us, from temptation. Lead us – don't let us fall. Lead us to salvation. Lead us to the wall.

"This is the way, the word of Allah, lost children of Babylon."

Finally, the renegade preacher is revealed.

Philip Parris Lynott is interred at St. Fintan's cemetery in Dublin, his headstone designed by Jim Fitzpatrick. He is survived, in part, by ATX's Grand Champeen and their haymaker, go-for-broke cover of "Cowboy Song." By Austin's Recliners swinging through "The Boys Are Back in Town" like it was a Harold Arlen or Hoagy Carmichael standard. And by Emo's Babylonian barkeep Houshang Ghaharie, who repeats Vagabonds of the Western World over and over and over on the club's jukebox as if it was the last platter on earth.

Musical blessings, all of them, but for Phil Lynott, 20 long years later and forever after, I still cry on the inside.