Wide-Angle Lens

The Ransom Center captures photography's history with striking breadth and focus

By Robert Faires, Fri., Oct. 1, 2010

The world's first photograph wasn't taken in Austin. And the legendary photographic cooperative Magnum Photos has never been headquartered here. But that hasn't stopped the city from developing into one of the major centers for the study of photography on the planet. With the Harry Ransom Center having made a home for some 5 million prints and negatives, including that groundbreaking first photographic image by Joseph Niépce and the whole of the Magnum archives (for the next few years, anyway), a wealth of the medium's most historic works may be found here. And not only does the University of Texas research center keep adding to those already vast holdings, it's also continually working up ways to share them with both scholars and the public. This year alone, the Ransom Center arranged with MSD Capital to host the Magnum Archive Collection for five years and made its 210,000 prints available for public viewing and study, filled the center's entire ground-floor exhibition space with a major show drawn from its extraordinary 35,000-photograph Gernsheim collection, published through UT Press a 350-page coffeetable book annotating 126 of that selfsame collection's most significant photos, and is devoting its biennial Flair Symposium, being held this weekend, to Shaping the History of Photography. Oh sure, the Ransom's rep may rest on its literary holdings – all those papers by David Foster Wallace, David Mamet, Norman Mailer, and their ilk – but this center takes the art of the camera as seriously as anything else.

In a very real way, the Ransom Center's commitment to photography begins with the collection amassed by Helmut and Alison Gernsheim over 18 years. It was the center's first major purchase of the kind, made by the "Great Acquisitor" Harry Ransom himself in 1963, shortly after he had established the Humanities Research Center at UT. And like so many of the acquisitions he made in those early years, it was a bargain. Though the Gernsheims had talked about placing their collection in a museum of photography – preferably one they would run in affiliation with an established institution or governmental body – almost from the moment the two historians began accumulating those thousands of images, a decade of negotiations with entities as far-flung as the Royal Photographic Society and the Victoria and Albert Museum in England; museums in Stockholm, Sweden, and Munich, Germany; the town of Lucerne, Switzerland; the Library of Congress; the Smithsonian Institution; and UNESCO, among many others, had yielded no results. Finally, after a traumatic experience in Detroit, Mich., in which the museum they'd been promised proved to be an unfunded fantasy, leading to a court seizure of their collection and multiple lawsuits, the wearied Gernsheims accepted an offer from Ransom to buy the collection outright. UT paid $300,000 – less than half of what the Gernsheims were asking, with no museum attached – and what it received in return were 35,000 original photographs spanning more than 130 years, more than 200 pieces of antique photographic equipment, and approximately 3,600 books, journals, and articles on photography. It was at the time the largest collection of photographs in private hands and arguably unparalleled in its depth of images from the medium's first century.

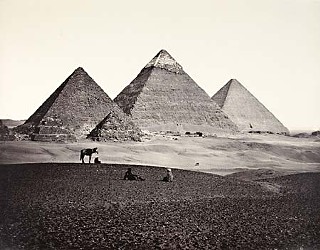

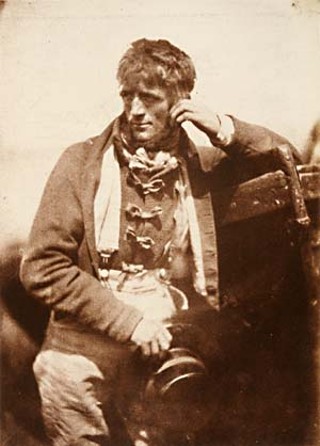

A stroll through the exhibition "Discovering the Language of Photography: The Gernsheim Collection" or a scan of the plates in its companion tome, The Gernsheim Collection, is all you need to grasp how rich and momentous this compendium is. Represented here are the many varied types of early photographs – heliograph, daguerreotype, chromatype, calotype, salted paper print, albumen print, carbon print, platinum print, photogravure – with images by a host of the field's pioneers and early masters: Louis Daguerre, Lewis Carroll, Julia Margaret Cameron, Eadweard Muybridge, Jacob Riis, and more. Then there is the bounty of images by their 20th century counterparts, the figures who propelled photography into the art form we recognize it as today, among them Man Ray, Robert Capa, Ansel Adams, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Paul Strand, Edward Weston, and Arnold Newman. In many cases, the Gernsheims were able to acquire signature photographs by these landmark artists.

In the book, Ransom Center senior research curator Roy Flukinger takes us through the evolution of photography one work at a time, giving each a lovingly large and crisp reproduction accompanied by a page of text that provides background on the image and its maker, as well as context for its importance in the medium's progression. In the exhibit, Ransom Center curator of photography David Coleman takes a broader historical view, grouping works by period to reveal how the technical developments in the field – the assorted experiments with chemicals on plates, the shrinkage of cameras from cumbersome bread boxes on tripods to handheld point-and-shoot devices – affected not only the quality of the photographic images over time but also the purposes for which they were taken (historical documentation, domestic portraiture, photojournalism, commercial and fashion illustration, personal expression, art!) and the kinds of people they were taken by (professionals, artists, everybody). The two projects may approach the Gernsheim collection and, by extension, photography's history from the opposing angles of micro and macro, but in both we can see a medium inventing itself, discovering how to do what it wants to do and then restlessly expanding the notions of what it is it wants to do. There's an impressive sense of scope in both exhibit and book, too – that take-your-breath-away breadth of the panoramic landscape shot (examples of which may also be found here) – but you also have the sense of just skimming the surface of the Gernsheims' treasures. Neither project includes even one-tenth of 1% of the collection. It is, in the words of Coleman, "the briefest thumbnail that you could possibly give," and he admits that "it was torture to not put more in."

However difficult it may have been for Coleman and Flukinger to decide what to include in and what to leave out of their respective surveys of the Gernsheim collection, the results reveal how judicious both men ultimately are as curators of photography. Throughout, their selections manage at once to be visually compelling (you want to study them, to drink in all the richness of their composition, shading, atmosphere, humanity), to be representative of the work of a particular artist or era, and to tell part of an overarching story. We're able to comprehend how one image led to another or to see echoes of one work in another made a continent or a century away. As with a photograph in a tray of developer fluid, the big picture materializes before our eyes.

The care taken with the Gernsheim collection projects has been evident in so many other Ransom Center exhibits on photography – "Fritz Henle: In Search of Beauty"; "Dress Up: Portrait and Performance in Victorian Photography"; "Ansel Adams: A Legacy"; "The Image Wrought: Historical Photographic Approaches in the Digital Age"; "Shooting Stars: The Golden Age of Hollywood Portraiture, 1925-1950"; "Photography's Turning Point: The Journal Camera Work"; "Go Out and Look: The Photography of Russell Lee" – that it makes one eager to see what the center will do with all those Magnum photos in the inevitable exhibition. (It will happen, Coleman assures me, but no date has been set.) In the meantime, we may savor these two works that tell the story of a pair of committed collectors and their incredible contribution to the history of photography, that tell the story of photography itself, and that provide one more chapter in the ongoing story of the Ransom Center's dedication to preserving and expanding the legacy of photographic art.

Gernsheim Exhibition Events

"Discovering the Language of Photography: The Gernsheim Collection," runs through Jan. 2, 2011, at the Ransom Center, 21st & Guadalupe. For more information on this and the related events listed below, call 471-8944 or visit www.hrc.utexas.edu.

Poetry on the Plaza: The Language of Photography features photographers reading poetry about photography. Readers include Roy Flukinger, Ransom Center senior research curator; Geoff Winningham, photographer, filmmaker, and journalist; and Matt Valentine, photographer and program coordinator of the Joynes Reading Room. Wednesday, Oct. 6, noon, on the Ransom Center Plaza, 21st & Guadalupe.

The Lives and Work of Helmut and Alison Gernsheim is a discussion of the two historians and collectors by J.B. Colson, professor emeritus of journalism and fellow of the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, and Roy Flukinger, Ransom Center senior research curator. Tuesday, Oct. 19, 7pm, in the Prothro Theatre of the Ransom Center, 21st & Guadalupe.

The Gernsheim Collection, by Roy Flukinger (UT Press, 360 pp., $75), features 126 full-page plates from the collection with accompanying text describing each photograph's place in the history of photography. An introductory essay looks at how Helmut and Alisa Gernsheim built their 35,000-photograph collection and their pioneering roles as historians of photography. The book's foreword is by Alison Nordström, George Eastman House curator of photographs. The afterword is by Mark Haworth-Booth, former curator at the Victoria and Albert Museum. Roy Flukinger is senior research curator of photography at the Ransom Center, where he also served as curator of the photography department for more than 25 years.